| story by | |

| photos by | Steven Hertzog |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

Understanding and protecting Douglas County’s rivers, lakes and wetlands is a multifaceted process including many state and local entities.

Connectivity of Water

Clouds blanketed Douglas County in early November, delivering showers that drenched runners, muddied construction sites and paused the county’s soybean harvest. Part of that moisture soaked into the ground, but much of it rushed over parking lots and fields, through creeks and ditches, and into the area’s rivers, lakes and wetlands.

That the water didn’t stay put isn’t surprising. What might be is how complicated managing its movement through the Kansas River Basin is. Rainfall that enters the Wakarusa River, Clinton Lake, Baker University Wetlands, Lone Star Lake, Douglas State Fishing Lake and countless other waterways eventually drains to a single point: the Kansas River. That flows into the Missouri River, then the Mississippi River and finally the Gulf of Mexico.

On the shore of the Kansas River

It’s all connected, so decisions made upstream and down by myriad local, city and state governments, federal agencies including the U.S. Corps of Engineers, nonprofits and other entities impact drinking water, flood control, recreation, industry and wildlife habitat in Douglas County. The system seems vast, but at the same time, it’s hyperlocal. Choices made by every local land user impact the quantity and quality of available water throughout the system, as farmers like Daniel Squires, of Lawrence, well know.

“Our kids are growing up playing on Clinton Lake,” says Squires, whose family has farmed in Douglas County since 1860. “We drink the water that comes out of the river and lake, and we want to make that just as safe as anybody else does. That’s a big reason this is important to farmers.”

The Lawrence farmer grows more than 1,500 acres of corn and soybeans in Douglas and Shawnee counties, all of which he plants without disturbing the soil, a practice known as no-till farming. He also plants cover crops such as cereal rye, tillage radishes and turnips to reduce erosion and nutrient runoff, suppress weeds, break pest cycles and improve soil permeability.

Cover crops have boosted organic matter in his soil, something Squires suspects has increased yields, particularly in fields with steeper grades or more marginal soils. Using no-till exclusively also means Squires doesn’t have to invest in or maintain conventional equipment, such as a field cultivator and disc for tilling or chisel (used for deep tillage), or spend the money, fuel and time required to use it. The equipment he does own is high-tech, allowing for precision-farming techniques like soil-sampling and exact applications of fertilizer.

The real benefit though? Crop residue and cover crops allow fields to absorb more water; any excess is slowed and filtered, leaving soil and fertilizer in place.

“What really sells people is when they get out there after a big rain in the spring and sit at the end of a terrace watching water run off,” Squires says. “It’s clean water coming out of the end of a terrace, not something that looks like a milkshake made with soil.”

Watershed Work

Squires didn’t get to this point by himself. He took over a few fields from an older farmer who was already planting cover crops, and he has since worked with the Kansas Alliance for Wetlands and Streams (KAWS) to expand the practice.

The nonprofit works with landowners, local conservation districts, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks (KDWP), the Kansas Department of Health and Environment, K-State Research and Extension, and other partners to connect people, land and water. Part of that work is sponsoring six watershed projects in the state’s Watershed Restoration and Protection Strategy (WRAPS) program. WRAPS helps stakeholders protect, restore and manage watersheds, and is financed through the Environmental Protection Agency’s Section 319 (which focuses on nonpoint sources of pollution) and the Kansas Water Plan.

Two of WRAPS watershed plans extend into Douglas County: the Upper Wakarusa River and the Lower Kansas River. The plans identify priority areas within each and offer cost-share assistance for producers working to establish best practices, such as developing grazing-management plans and alternative watering systems for livestock, planting filter strips and buffers, stabilizing stream banks, converting to no-till and planting cover crops. KAWS even makes specialized equipment available, such as the Hagie Montag interseeder, which can sow cover-crop seed into a field where corn is already growing.

Farmers such as Luke Ulrich, of Baldwin City, are happy to take advantage of such opportunities.

“Everything we do in our operation at some point flows into a stream or river that will end up carrying our soil and nutrients away if we’re not careful,” says Ulrich, who is committed to improving soil and water quality on the 2,100 acres of row crops he farms. Most of that is in Douglas County, and a “pretty good chunk” lies in the Upper Wakarusa River watershed.

He began switching to no-till farming about 10 years ago to combat topsoil loss and erosion. He acknowledges the change felt risky—farmers rely on familiar, proven methods because of the investment it takes to produce a crop.

“We have one shot every year, and it has to count,” Ulrich says. “You don’t want to not raise a crop because of a management decision.”

The shift appears to be paying off. The small rills and ditches cut by running water have disappeared from his fields, and he spends less time doing “dirt work” such as repairing terraces. Ulrich is collaborating with KAWS to plant cover crops that suppress weeds like marestail (also called horseweed) and pigweed, add organic matter and keep topsoil and fertilizer in place. Ulrich, of course, hopes such practices will prove profitable, but his efforts aren’t just about making money. It’s about preserving a legacy—he is a sixth-generation farmer, and he hopes his 8-year-old son will become the seventh.

“We want to preserve this life, preserve this land, keep things viable and continue to make a living by feeding people,” he adds.

KAWS and its partners aren’t the only ones trying to make that happen. The Douglas County Conservation District (Ulrich serves on its board) offers educational and cost-sharing programs. Douglas County’s four drainage districts, each with their own elected board members and taxing authority, maintain a system of ditches that link fields and waterways. Producer organizations like the Kansas Soybean Association and Kansas Corn have their own initiatives to lessen the impact of water flowing over farm ground.

Kansas River near St. George photo by Lisa Grossman

The Essential Kansas River

It takes more than farmers to protect Kansas’s water resources, though. Approximately 80 percent of the state’s surface water is impaired by something, says Megan Rush, the Middle and Lower Kansas River WRAPS watershed coordinator for KAWS. That includes 100 percent of the Kansas River, which is an essential source of drinking water for 800,000 Kansans.

“That doesn’t mean you can’t drink out of it or recreate in it, but that’s still pretty scary,” Rush says. “That’s quite a few people who’d be without water if that resource goes away.”

The Kansas River originates near Junction City, and its drainage area covers more than 60,000 square miles from the High Plains of eastern Colorado to parts of Nebraska and most of central Kansas. It extends 173 miles through 10 Kansas counties before meeting up with the Missouri River in Kansas City, Kansas. Communities all along the way pull drinking water from the river; it also feeds alluvial aquifers that provide water for still more people.

That makes water quality a paramount issue, says Kansas Riverkeeper Dawn Buehler, who is also executive director of Friends of the Kaw and chair of the Kansas Water Authority, a 13-person board that advises the Kansas Water Office, governor and legislature on water-policy issues and the Kansas Water Plan.

Bacteria, agricultural chemicals including phosphorus and nitrates, and algal blooms in reservoirs are all issues, as are shoreline development, dredging, trash and one of the things Buehler dislikes seeing the most while canoeing the Kansas River: plastic.

“I’ll pull up on a sandbar and see little, tiny pieces of plastic, and water bottles are everywhere,” she says. “Not Pepsi bottles, not Mountain Dew bottles, but bottles for something you can get from your tap.”

Urban development takes a toll, too. New streets, parking lots and buildings change how water flows, creating more and faster runoff in waterways like Baldwin Creek, in northwest Lawrence, Burroughs Creek, in east Lawrence, and Yankee Tank Creek, which passes through Alvamar Lake above the Clinton Lake Sports Complex. Originally built as a flood-control dam in 1974, Alvamar Lake (then known as Yankee Tank Lake) was emptied in 2007 because of safety concerns. The dam and spillway were later upgraded and the lake refilled; it is still supervised by the Wakarusa Watershed Joint District No. 35, one of two watershed districts with taxing authority in Douglas County.

Heavy rainfall can flood the existing stormwater systems in Lawrence, as happened in August 2019. Excessive runoff from a deluge overwhelmed the Kansas River Wastewater Treatment Plant and allowed sewage to be released into the Kansas River and area creeks.

“Runoff came in so big and fast into the wastewater treatment plant that it broke the equipment,” Buehler recalls.

top to bottom Brian Squires plowing his fifield and examining his crop Ruts caused by runoff that have not been looked after and repaired become obstacles to the farmland. Luke Ulrich shows off the richness of the soil when he uses the non-till method

Clinton Lake Community

That summer proved difficult for Clinton Lake, as well. Widespread rains raised water levels throughout the Kansas River Basin, but Clinton Lake couldn’t release stored water because doing so would have exacerbated flooding and threatened levies on the Missouri River. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ water-management team in Kansas City worked with its counterparts in Omaha, Nebraska, Mississippi and elsewhere to monitor flooding while coordinating with the City of Lawrence, Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks (KDWP), Kansas Water Office, Clinton Marina and other entities locally. It wasn’t easy, and it meant curtailing recreation on the lake until levels returned to normal.

“The biggest thing about Clinton is knowing that it is a juggling act with multiple agencies and the public itself to take care of this resource correctly,” says Samantha Jones, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers natural resource manager at Clinton Lake. “It really does take an entire community.”

Flood control has been one of Clinton Lake’s main jobs since the dam was completed in 1977; another is providing drinking water for 100,000 area residents. Three Corps rangers plus maintenance staff and seasonal employees, oversee the 7,000-acre lake and the surrounding 15,000 acres of Corps-owned land. They’re also in charge of the lake’s parks, wildlife areas and other systems and amenities, which together attract 2 million visitors a year.

Then there’s the water itself. The Corps monitors the lake for problems such as sedimentation, something all Kansas lakes struggle with. Fast-flowing water in rivers and streams picks up soil. When that water enters a lake, its velocity slows, and those particles settle out. Over time, a buildup of sediment reduces a lake’s holding capacity.

At Clinton Lake, tracts of marshes, wetlands, deciduous forest and native grassland in wildlife areas help protect it from sedimentation. The Corps is working with KAWS and other partners to develop even more areas, such as an 80-acre wetland-restoration project along the Wakarusa River, near the Shawnee-Douglas County border. Construction is just starting; when finished in March, it will filter runoff, make it easier for Lawrence to treat drinking water and enhance recreation, says Rebecca Steadman, the Upper Wakarusa River WRAPS watershed coordinator for KAWS. The nonprofit is already collecting water samples to evaluate the wetland’s impact and will continue to do so for the next three years, she says.

“Hopefully, it will give us some documentation and validation while quantifying the benefits you get from restoration,” Steadman says.

Invasive species such as zebra mussels also bear watching. The mollusks can harm native species and habitat, clog pipes at water-treatment facilities and spur algal blooms. Some forms of blue-green algae are harmful to people and dogs. Others produce a compound called geosmin, which has a strong, musty odor that is difficult to remove from drinking water.

Other nuisances are silver carp, which have been found in Douglas County but not yet in Clinton Lake, and the rusty crayfish, which causes ecological damage, attacks people and animals, and was identified in Kansas in July. Aquatic plants including Eurasian watermilfoil, which forms dense mats on water surfaces, are also problematic.

“The biggest thing we fight is invasive fish and aquatic plant species,” says John Reinke, Northeast Region fisheries supervisor for the Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism.

The entrance to the “tower” at Clinton Lake

Valuing Recreation

Protecting lakes is important for Kansas, where fishing alone generated $6.8 million in user fees and added $293 million to the Kansas economy, the state’s wildlife and parks department reported in 2018. The department is financed entirely through hunting and fishing license fees and the Sport Fish Restoration Program, a federal program that levies excise tax on fishing equipment and boat fuel.

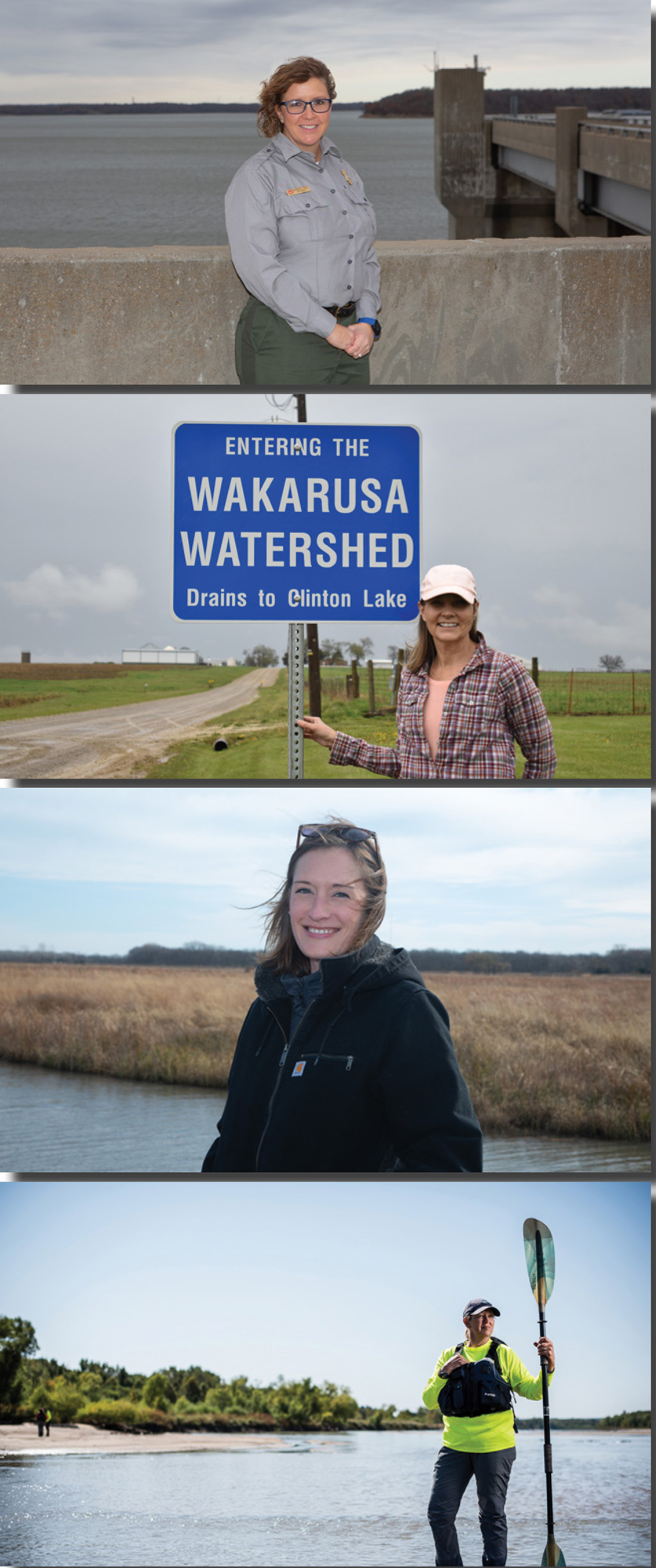

Samantha Jones, Natural Resource Manager U.S. Army Corp of Engineers; Rebecca Steadman, WRAPS Watershed Coordinator for the Upper Wakarusa Photo by Dayna Steadman; Megan Rush, WRAPS Watershed Coordinator Middle and Lower Kansas River; Dawn Buehler on the Kaw Photo by Dan Videtich

The KDWP owns and operates more than 40 state fishing lakes, including Douglas State Fishing Lake, two miles northeast of Baldwin City. The 180-acre lake has channel and flathead catfish, carp, largemouth bass, bluegill and crappie, while the surrounding 538 acres are open for in-season deer, turkey, squirrel and migratory waterfowl hunting. Primitive campsites, restrooms and picnic tables are also available. That’s all good for the local economy, Reinke says.

“The recreational opportunities, especially in a relatively urban area like Lawrence, are really important,” he continues. “Employers and business owners know that quality of life for their employees is a big thing.”

Chad Voigt, public works director for Douglas County, agrees. The county’s Lone Star Lake is about 10 miles southwest of Lawrence and offers 63 campsites, a beach, shelters, a playground, a newly remodeled community room and a handicap-accessible boat dock. It’s open to canoeing and kayaking, and the lake in September hosted the College Swimming and Diving Coaches Association of America National Collegiate 5K Open Water Swimming Championship. There are also 400 acres of parkland and plenty of wildlife, including bald eagle nesting sites, Voigt says.

It’s not hyperbole to say the lake was a gift for Douglas County residents. Work on the 185-acre lake began in 1934 as a Civilian Conservation Corps project. Ownership was transferred to Douglas County in 1937, and construction was completed two years later.

“We’re pretty lucky that we received it, because there’s no way we’d be able to build something like that today,” Voigt says.

Washington Creek flows into the lake, which Voigt explains was not designed for flood control, and then continues through a spillway and on to the Wakarusa River. Douglas County oversees mowing, weed control, tree management and facilities maintenance, and employs a seasonal camp host. The county charges camping and building-use fees; the lake and park are otherwise free and open to the public.

“This is not a money-maker,” Voigt says. “It’s an investment for the public.”

Maintaining such assets can be challenging, however. Baldwin City Lake is a historical spring 2½ miles southeast of Baldwin City, but a spillway that contained the water failed years ago. The lake is now “basically a swamp,” says Cory Venable, who grew up on an adjacent property and is now on the Baldwin City Council.

The city owns the property and is considering what to do with it as part of its strategic-planning process. Restoring the lake, which still has a disc golf course, could add to the city’s quality of life, but the council must consider repairs within the context of other fiscal priorities.

“I grew up on the lake, and I have a deep attachment to it, but it’s public money,” says Venable, who also owns the Baldwin City Beer Co. “I have to be objective about it.”

Building the Baker University Wetlands

Balancing competing priorities can be difficult, as evidenced by the long and sometimes contentious debate over how construction of the South Lawrence Trafficway would impact the Baker University Wetlands. Opponents worried it would ruin the wetlands; an eventual compromise actually expanded it. The wetlands complex now encompasses 927 acres, with 11 miles of hiking trails and a Discovery Center.

“On the whole, I would say we’re better off for those 900-plus acres being under rehabilitation and being put back into a natural system,” says Irene Unger, director of the Baker University Wetlands.

The wetlands evolved during thousands of years of flooding, which gradually formed a natural levee along the Wakarusa River and left layers of clay that prevent water from percolating quickly through the soil, according to the Baker University Wetlands website. The original wetlands were homesteaded in 1854 and later acquired by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to create a farm for Haskell Institute, a precursor of Haskell Indian Nations University. Most of that land was drained for agricultural use, as was typical of the time.

“There’s a long history in the United States of converting wetlands into agricultural land,” Unger says.

Much of the acreage was declared surplus land by the Department of the Interior and given away in the 1950s, and Baker University acquired 573 acres in 1968. Early restoration efforts included reintroducing native plants. In the 1990s and 2000s, drainage structures were removed, the swales and pools of the original landscape were excavated, and boardwalks were built.

A 2012 mitigation agreement between the Kansas Department of Transportation and Baker University meant 56 acres were lost to the trafficway, but 410 more were added. This allowed for the expanded restoration of wetlands, prairie and native riparian forest; creation of buffer zones; relocation of utility lines; construction of trails, parking lots and the Discovery Center; and increased educational and recreational opportunities for Baker University students and the public.

The wetlands can now do what they’re meant to: slow and filter water. Unger likens it to a sponge—when excess water enters the wetlands, the system soaks it up and then gradually releases it. That’s exactly what happened during those wet months of 2019, when the Wakarusa River was running so high that water backed up into the wetlands.

“It received all that water, held it and slowly released it,” Unger says. “That was nature doing its thing.”

Two full-time and two part-time staff manage the Baker University Wetlands through mowing, controlled burns and elimination of invasive species like sericea lespedeza and purple loosestrife. They also do everything from creating educational programming and collecting water quality data to operating the Discovery Center and picking up trash. But their work is more than a sum of tasks.

Friends of the Kaw and volunteers work cleaning up the Kaw Photos by Lisa Grossman

Making Preservation Personal

Baker University Wetlands’ goal is to create a functional and biodiverse ecosystem that filters water and provides a refuge for plant, animal and insect species, as well as educational and recreational opportunities for people.

“It’s really hard to quantify those benefits,” Unger says. “People talk to me about their experiences during the pandemic, and there’s not a dollar amount you can put on improving mental health by being in nature.”

Such personal connections are essential to protecting natural water resources, Riverkeeper Buehler says. That’s why Friends of the Kaw organizes paddle trips and restoration workdays, holds events including beer and film festivals, and this year, celebrated its 30th anniversary with a party on a sandbar at the Kaw River State Park, in Topeka.

Many of the organization’s supporters enjoy canoeing and kayaking, and those two activities generate about $3.7 million in revenue annually in Kansas, according to the river conservation group America’s Rivers. Even more people hike, bike and camp near waterways. Wildlife is also a big draw—the Kansas River is thick with blue herons, kingfishers, white pelicans, migratory birds like ducks and geese, softshell turtles, river otters, beavers and other species. There is even a record 27 pair of nesting bald eagles along the Kansas River now, Buehler adds.

“When people find a connection to a river, they fall in love with it and want to help protect it,” she says. “It changes their perspective.” p

![]()