| story by | |

| photos by | Douglas County Historical Society, Watkins Museum of History |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

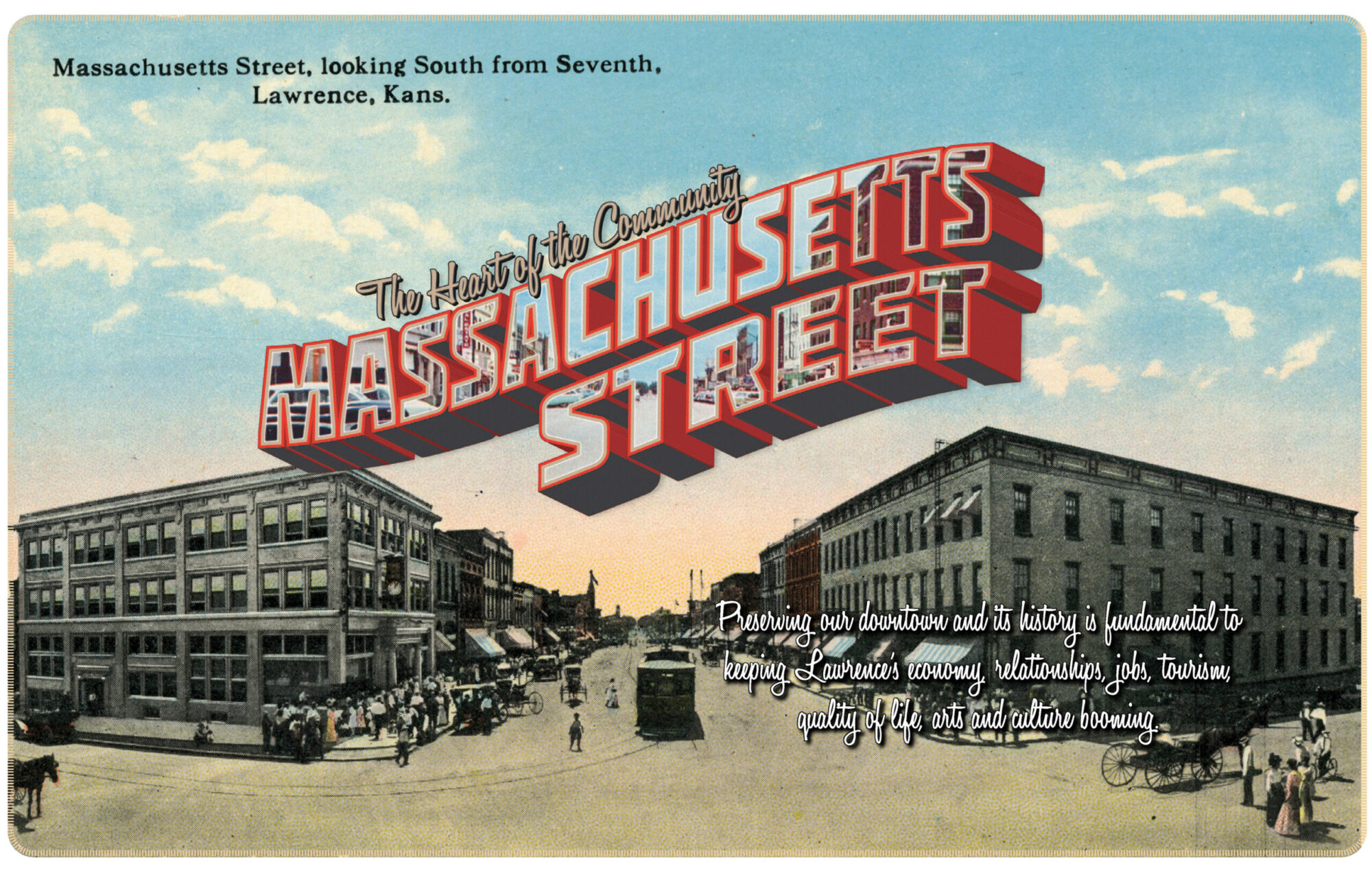

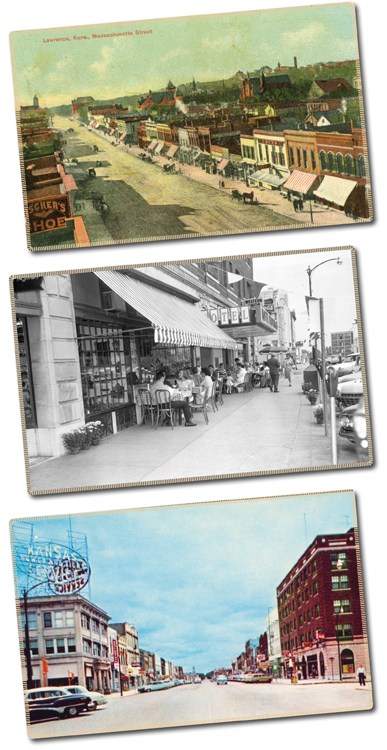

The Heart of the Community: Massachusetts Street. Preserving our downtown and its history is fundamental to keeping Lawrence’s economy, relationships, jobs, tourism, quality of life, arts and culture booming.

The Heart of the Community: Massachusetts Street. Preserving our downtown and its history is fundamental to keeping Lawrence’s economy, relationships, jobs, tourism, quality of life, arts and culture booming.

The Heart of the Community

Downtown. What does that word mean to you? Shops. Restaurants. Arts. Businesses. Cafes. Nightlife. Culture. Entertainment. Community. Museums. History.

For many of us, it’s all of the above. Downtowns are the soul of any city and essential to its success. Across the country, many of our downtowns were once among the oldest neighborhoods in town, meaning they now contain a unique insight into the past. Their historical landmarks, monuments, buildings and distinct features offer a rare glimpse into the past only witnessed by those things that have stood the test of time. Knowing that history can lead to the preservation of a downtown’s future.

“Travel teaches you many things, not the least of which is that downtowns matter,” explains Edward McMahon, a leading authority on topics such as health and the built environment, sustainable development, land conservation, smart growth and historic preservation. “Downtowns are the heart and soul of our communities.”

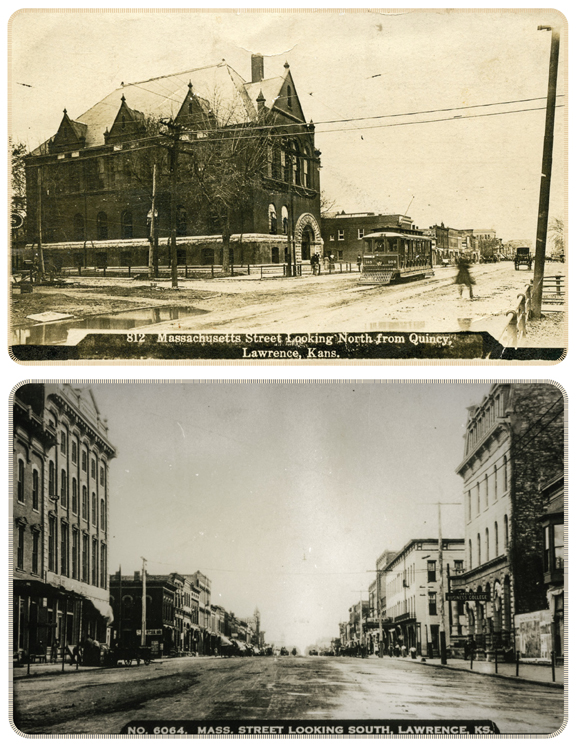

Steve Nowak, executive director of the Douglas County Historical Society, which operates the Watkins Museum of History, agrees. “Massachusetts Street has been the heart of the community since the city’s founding and, in a way, the street reflects the community’s growth and change,” he explains. “It is certainly home to some of the city’s most historic buildings and also serves as a community gathering place.”

“Mass. Street,” as locals call it, is the main street that runs through Downtown Lawrence. Much of it listed on the National Register of Historical Places under Lawrence’s Historical District, the 600 through 1200 blocks of Massachusetts Street were settled prior to the Civil War and have been through their fair share of hard times.

During Quantrill’s Raid, much of the downtown business district was burned to the ground, he continues. Only two buildings were left standing in the Mass. Street business district. The most prominent building lost at the time was The Eldridge Hotel.

The Heart of the Community

The Famous and the Infamous

“The Eldridge Hotel has been an integral part of the history of Lawrence since its founding,” explains David Longhurst, part owner of the hotel since the 1980s. The original building on this site was the Free State Hotel, built in 1855 by settlers from the New England Emigrant Aid Society in Boston. The Free State Hotel, intended as temporary quarters for settlers who came here from Boston, was named so to make clear the intent of those early settlers: that Kansas should come into the Union as a free state.

“Think about the investment of time, money and resources into the Eldridge Hotel,” he continues, “beginning with settlers who came to Lawrence and built the Free State Hotel in 1855.” Sheriff Sam Jones and other renegade confederates burned it down the day it opened in 1856. Col. Shalor Eldridge came to Lawrence and rebuilt the hotel again, naming it the Hotel Eldridge. Confederate guerrilla leader William Quantrill raided Lawrence in 1863 and killed more than 150 people, tragically burning and destroying the symbolic city. Once again, time, money and resources were needed to rebuild the hotel for the third time, Longhurst explains.

“The Eldridge Hotel stood until 1925 as one of the finest hotels this side of the Mississippi and continued to play an important role in the early development of Lawrence and the State of Kansas,” he adds.

But by 1925, the hotel had deteriorated, and Lawrence businessman Billy Hutson rebuilt the hotel for the fourth time “because of its importance to the city of Lawrence, and [to]restore it to its former place of dignity and elegance,” Longhurst says. “The community stepped forward and made the investment necessary to ensure the success of this important undertaking. Once again, the Eldridge Hotel was a premiere hotel in Lawrence, in Kansas and west of the Mississippi.”

By the late 1960s, trends had changed, and downtown hotels were losing business and becoming less prevalent. The Eldridge was not immune and finally closed its doors as a hotel on July 1, 1970. “In fact, a key had to be made to lock the front door because it had been lost many years earlier,” he says.

In 1970, the Eldridge was converted to the Eldridge House Apartments, and in 1985, another group of investors put in money along with $2 million in industrial revenue bonds from the City of Lawrence to convert the Eldridge back to a hotel. In 2004, yet another group of investors bought the Eldridge and invested even more millions of dollars to completely remodel the hotel. “And thus began the rebirth and renovation of our historic hotel,” Longhurst says. “This multimillion-dollar renovation project restored the building to its original 1925 grandeur.”

Reopening in May 2005, the hotel once again assumed its role as Lawrence’s premier hotel. “Occupying the most historic corner in Kansas, the Eldridge truly is the place where ‘history and hospitality converge,’ ” he says.

With its long and complex history, the Eldridge Hotel is one of Lawrence’s most famous stories of reinvention and restoration. But it’s not the only one.

The Heart of the Community

A House of History

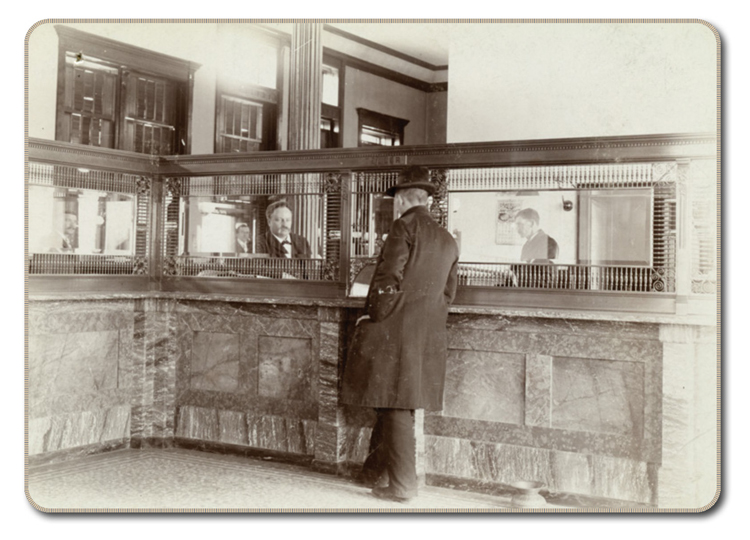

Watkins’ Nowak says that nearly everything about the Watkins Building is unique. “As a history museum, we consider our building to be our biggest artifact. The grand nature of the building certainly helps draw attention to the museum and make us memorable.” A classic example of the Richardsonian Romanesque influence on Kansas’s architecture, it was considered one of the most magnificent buildings west of the Mississippi River at the time of its construction.

At a time when Mass. Street was still a dirt road (1888), J.B. Watkins hired architects from Chicago to design the headquarters for his business empire. The building they designed included a number of technological advances and modern business conveniences. And Watkins spared no expense on the decor, Nowak continues. “Terra cotta ornaments on the exterior, mosaic floors, marble wainscoting, plaster-decorated ceilings, a cast-iron and marble staircase, and oak and exotic curly yellow pine woodwork.”

The building included six vaults with doors made in Cincinnati, as well as both gas and electric lighting. “There was even an electric-powered employee call button system and a telephone,” he adds. The windows were a marvel of modern technology at the time, as the process for producing plate glass was invented in the 1880s.

In 1888, the Watkins National Bank was established on the ground floor of the building. The original cost of the building was $100,000 (replacement cost today would be over $20,000,000).

Watkins’ wife, Elizabeth Miller Watkins, donated the building to the City in 1929, and it was used as City Hall until 1970. In April 1975, after being restored, it became the home of the Elizabeth M. Watkins Museum. More recently, the name was changed to the Watkins Museum of History to clarify the museum’s focus.

“The building was unlike anything else in Lawrence and unique among buildings west of the Missouri River,” Nowak says. “It marked J.B.’s success as a businessman but also Lawrence’s transition from frontier town to Midwestern city.”

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

The Heart of the Community

What began as Kansas’ first abolitionist newspaper, The Herald of Freedom, in the mid-1850s, Liberty Hall has a varied history that includes burning twice and being rebuilt by materials asserted to be “completely fireproof.”

After first being burned down during the Sack of Lawrence by Sheriff Jones, a new structure was rebuilt in 1856. The structure at 644 Massachusetts St. next became a gathering spot for debates, meetings and political speeches. In 1882, J.D. Bowersock purchased and renovated the building, adding another floor and creating the Bowersock Opera House, a theatrically themed opera house and well-known entertainment destination. About 30 years later, an electrical fire burned the opera house to the ground. So Bowersock rebuilt the building we know today as Liberty Hall.

Over the next century, the building housed a theater, an inn and night club, a disco and now, a video store, coffee shop, cinema and community gathering spot. Next year, in 2022, the building at Seventh and Massachusetts streets will have stood strong for 110 years.

Genelle Denneny, Liberty Hall office manager, believes preserving a town’s history is important, acknowledging that operating within an older building like the one that houses Liberty Hall can be costly. “I know that preserving old buildings is not cheap. I feel there are a lot of businesses in old buildings that struggle with dated utilities, structural issues, heating/cooling [costs]. It is a situation where you weigh the solutions with the reality of what can be afforded: What are the priorities?

“It is important to try to preserve history in any town, good, bad or ugly, because if you don’t … it could repeat itself,” she continues. “Lawrence has a history of good, bad and ugly: Acknowledging that is reality.”

Denneny explains that Liberty Hall is unique in that today, it has a variety of businesses that appeal to all types of people: movies, videos, coffee, music, entertainment—something for everyone. “The building itself is so beautiful to wander around in, it makes a special event even more inviting,” she says. And “It’s fun to work downtown. There is usually something going on; the service businesses have a subculture where people know each other simply by seeing each other from day to day.”

Documenting the Past

The Heart of the Community

The Block-by-Block research project began in the spring of 2017 in a journalism class at the University of Kansas, in which students learn to find information and evaluate its credibility. Searching for an activity that would help students integrate concepts about sources, research and attribution, Peter Bobkowski, associate professor, was inspired by a feature in New York Magazine that told the stories of buildings and people who worked and lived in them over the decades. His students, with help from other community leaders, were tasked with creating a business timeline of a historic building picked by the group.

“Students choose KU in part because of the unique character of Lawrence, and Mass. Street is an important part of that,” he explains. “So helping them make those connections between the town’s history and what appealed to them about this town was rewarding.”

Each of the historic buildings downtown tells a number of fascinating stories. Free State Brewing Co. and The Granada are just a couple of the buildings students studied for this project.

From Bus Depot to Beer Joint

According to Block by Block, the building at 636 Massachusetts St. began as an immigrant-owned grocery store. When the owner became too old to run the store around 1906, he moved to Chicago to live with his daughter.

“The previous building was destroyed in the tornado of 1912, so all that remained were the stone walls on either side,” explains Chuck Magerl, owner of Free State Brewing Co. “It was rebuilt as the Lawrence Depot for the Kaw Valley Interurban electric train line that ran to Kansas City. In the 1930s, it became the bus depot, and tens of thousands of students and Lawrence visitors came and went through this location.”

The Kaw Valley Line, connecting Lawrence and Kansas City, was owned by JJ Heim, a brewing company bottling plant owner. The plan was to continue the line on to Topeka, which never happened. Ridership declined in the 1920s, and the last ride was taken in 1935. According to Block by Block, the wooden cross beams in the building today were once used to suspend the wires for the cars, one of the few remaining reminders of the trolley days.

In 1989, what we know today as Free State Brewing Co. began leasing the space from Liberty Hall Associates. Famous for being the first microbrewery to open in the state of Kansas in 100 years, Free State has seen its share of students, visitors and locals, as well as some notable personalities. “Too many to truly count,” Magerl says. “Allen Ginsburg, Aaron Rogers, Joan Baez, Ann Coulter, Wes Jackson, Patty Jenkins, Bobby Knight, Rachel Maddow, Chris Piper, Dick Vitale and so many more.”

Legendary Locale

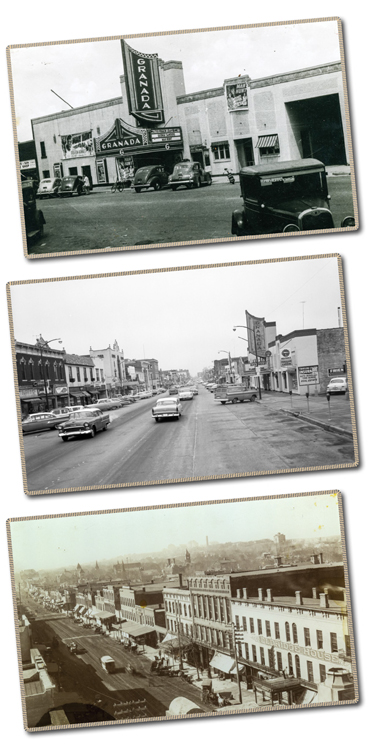

Mike Logan, owner/operator of The Granada, 1020 Massachusetts St., says the original Granada was built as a silent film theater. “Flash-forward to today, and I guarantee when The Granada is operating, it is anything but silent.”

According to Block by Block, it began as a grocery store in 1905. In 1907, it became a carpenter’s shop. Next, in 1908, a roller-skating rink called The Auditorium opened in the space. It was a time of “skating fever,” and the rink even employed a band for music. Because of the number of skating-related injuries, the mayor of Lawrence decided to prohibit skating in town. Soon after, The Auditorium closed.

In 1919, an auto repair garage and gas station operated in the space. In 1923, the location became a Ford and Lincoln dealership.

In September 1934, Stanley Schwahn, owner of the Patee Theater and president of the Commonwealth Theater, remodeled the lot into The Granada Theater, complete with a large, vertical neon sign and a marquee covering the sidewalk. It was said to be the most modern theater in Lawrence.

The theater’s opening picture was “Hide-Out” (1934). Public events were also held as advertising, featuring giveaways of cars, vacations and house appliances. Movies such as “Stagecoach” (1939), “Gone with the Wind” (1939) and “Bachelor in Paradise” (1961) also came to The Granada.

In 1989, United Artists sold The Granada, and soon after, Mike Elwell, a former Douglas County district judge, bought it and transformed it into a coffee shop and nightclub. He preserved all of the original ware and structure, including the ticket booth dispenser and original movie posters, to create an atmosphere like what it would have been during the 1930s. The venue played light jazz music from 4 to 9 p.m. then transformed into a nightclub.

Elwell sold the Granada in 2005 to Consolidated Properties LLC, owned by Doug Compton. Consolidated planned to create a home court location for KU’s tennis teams, to no avail. Logan leased the space in 2003 and still runs The Granada today.

“Our history defines Lawrence’s character,” Logan says. “The preservation of our buildings and history are one major way for Lawrence to tell it’s story.”

The Granada has been hosting live music since 1993. Some noteworthy national and international artists include: M83, The Get Up Kids, Ben Folds, Flaming Lips, Weezer, Henry Rollins, Pat Green, G-Love & Special Sauce, Marilyn Manson, Dirty Projectors, Jerry Cantrell, Murder by Death, Big Head Todd, Smashing Pumpkins, Rusted Root, John Mayer, Creed, Blink 182, The Roots, Jack’s Mannequin, Walk the Moon, The Killers, Phoenix and Snow Patrol.

The Granada is currently making improvements for both the band and the fan, Logan explains. “The shutdown due to COVID has given us a lot of time to try and figure out how to best reinvest in the space in consideration of a reopening, and return to being an active attractor to talent from across the globe. We are proud that we have been able to keep the building alive with live music and are looking forward to the next chapter for the venue… ”

Though Block by Block is no longer a J-School project, a lot of great information was discovered and noted by KU journalism students during this time. “One of the reasons that we don’t do the project anymore (we stopped a few semesters ago),” Bobkowski explains, “is that there is no infrastructure to gather the information that the students researched and display it to the public in a way that would be accessible and useful.” He says he would like to convert that information into something the public can consume but hasn’t found anyone willing to collaborate with him to help him store and disseminate the information to the public.

“There is a lot of great information here, and Lawrence could be a pioneer in preserving and sharing this type of information with the public; but it’s not something I can do by myself,” he says.

Preservation a Priority

Preserving a community’s historic and cultural heritage is vital to its identity and that of its community members. But with continued outside distractions such as budget concerns and competing priorities, ensuring that a town’s historic and cultural stories are told is only getting harder.

“The awareness of Downtown’s importance both economically and culturally shown by both the community and by city government is a very important part of preservation,” Watkins’ Nowak explains. “It is hard to expend effort preserving something that you don’t appreciate, and the community really seems to appreciate Lawrence’s history and how that is reflected in Downtown.”

He believes efforts to ensure that Downtown has something to offer all residents are an important part of preservation. “The best way to build support for Downtown is for people to use it and make it a regular part of their daily lives.”

Historic preservation can be complicated and nearly always requires partnerships among private, public or governmental groups. But by preserving our significant historical sites, we ensure our varied cultural identities will continue to be enhanced.

“Mass Street serves as a reminder of who we are as a community—what we have been through, how we have grown and changed, what is important to us,” Nowak explains. “It is a reminder of our past but also a symbol of our character as a community now.” p

![]()