| story by | |

| photos by | Steven Hertzog |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

The process of naming parks and streets in Lawrence changes with the times and is unique because of the town’s history.

The History in the Names

We don’t give it a second thought when we tell someone to “head west on Bob Billings” or “turn right on Kasold,” or “meet up in the shelter at Holcom Park.” In a sense, that is exactly what the predecessors in Lawrence had in mind when they chose the names for streets and parks. Their goal was to preserve the names of those people who had a major impact on the town and make them household names for decades.

So who are the people behind the names? And how and why were those names chosen? The street and park names in Lawrence tend to fall into these four categories: to honor someone for their accomplishments or contributions; developers naming after themselves, or the city naming properties for those who bequested property or parks funds to the city; for nearby streets or geographic features that define an area; are unnamed or awaiting potential sponsored naming rights.

Before outlining and recapping the namesakes of some of Lawrence’s better-known streets and parks, it is worth exploring the modern-day processes for how each are named.

Street Signs

Naming Streets

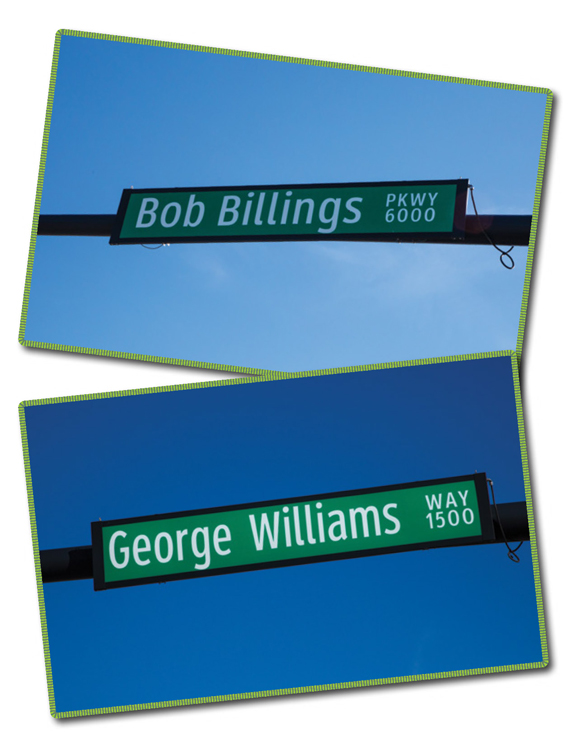

It is rare for a main artery or public street to need a name nowadays. The only major nonnumbered artery that has been named in the past 20 years is George Williams Way, which is detailed below. In that same time frame, one major street was renamed, and that is Bob Billings Parkway, formerly 15th Street. Both of these were named by City Commission approval. Future major street naming likely would follow a similar process, says David Cronin, city engineer with Municipal Services and Operations for the City of Lawrence.

Residential street naming follows a much less public process, Cronin explains. Developers name the streets themselves in subdivisions and neighborhood developments, and they have wide latitude to choose names as they see fit. The City reviews the street names, mostly on a cursory level. They want to make sure there are not duplicate street names elsewhere in town, and any streets that are an extension of an existing street maintain that name for consistency. The only thing the city code explicitly does not allow in a street name is compass directions as any part of the name. It also specifies that cul-de-sacs or dead ends must be named “Court,” while streets that start and end attached to another street must be named “Circle.” The City Commission gives final approval for the names based on the City staff’s recommendations, he says.

Naming Parks

Parks in Lawrence receive their names from one of two sources. The most typical route has been that a name is proposed and then receives a vote from the City Commission for approval. That process has applied to parks with people’s names and those named for streets, neighborhoods or other geographic features. The other way is to name the park for whomever donated the property or bequested money to the city to be used to create a park.

There are many examples of each of these, spanning the decades and even centuries, thanks to thorough research by Roger Steinbrock, who heads up the marketing division of Lawrence Parks and Recreation.

One interesting exception to the above categories of honorifics and bequests is Broken Arrow Park, at 2800 Louisiana St. The land for the park was donated to the city, school district, county and township by the U.S. Department of the Interior in 1959, according to Steinbrock’s research. The park’s name, Broken Arrow, was the result of an essay contest at what is now Haskell Indian Nations University. The student with the winning essay was awarded $50 for the description of a broken arrow as a symbol of peace.

An Evolving Process

Street Signs

In surveying the names of parks and city spaces in Lawrence, the history of honorific park names is very low on women and people of color. It is easiest to name the exceptions to this in alphabetical order: Martin Park, Pat Dawson Billings Nature Area, Sandra Shaw Community Health Park, Viola and Conrad McGrew Nature Preserve and Woody Park. The Kathy Fode Room in the Parks and Recreation administrative building is named to honor Fode’s retirement. Hobbs Park is named for a woman, Myra Hobbs, but she provided the funds for a park in a bequest, so it is not an honorific.

The Parks and Recreation Advisory Board will begin work this spring to devise a formal process for naming future parks based on best practices of other cities. That process will need to be approved by the City Commission, which should happen sometime before the fall, says Derek Rogers, Lawrence’s director of Parks & Recreation.

“It should be a public process, getting community input on naming parks. Neighborhood associations and other entities should have a say,” Rogers says.

Likely a new park will be named this year on the grounds of the city’s new police headquarters. Not including that space, there are five park properties that do not have names, says Mark Hecker, assistant director of parks for Lawrence Parks & Recreation Department.

Other well-established city recreation properties have retained their initial generic names since they opened: the Outdoor Aquatic Center, the Indoor Aquatic Center, the skate park, the Mutt Run off-leash dog area, the disc golf course in Centennial Park, to name a few.

The City Commission approved a sponsorship program in 2017 that applies to Parks and Recreation facilities, programs and events. So with the right sponsorship or partnership, unnamed sites could acquire an additional moniker. Sponsors must be consistent with the City’s public mission and core services, with options for naming rights, annual sponsorships and community support, and specific parameters for each.

THE LEGACY OF PLACE NAMES

A Word About the State Streets

It is impossible to discuss the names of streets in Lawrence without acknowledging the state streets in the city’s central core. As it turns out, the city founders were using those street names to send a clear political message at the time and for future generations. But seeing that message requires a bit closer examination of all the names.

The New England Emigrant Aid Society named the streets when it arrived in 1854, naming Massachusetts Street after their home state but getting crafty as they named streets east of Mass. Starting with Delaware Street, the streets are in the order they entered into the Union, but not exactly: The New England abolitionists deliberately left out two Confederate states that should be in that sequence, Georgia and South Carolina, according to research by local historian Steve Jansen. Then, west of Mass. St., the streets resume the proper order until Texas is also left out.

So Lawrence’s original street names were more about who was not named than who was named. We have states of the Union, in order, but the city’s founders thought that slave states did not merit recognition in the abolitionist era.

Honoring People With Streets and Parks

A couple of Lawrence’s main artery streets are named in honor of people: Bob Billings Parkway and George Williams Way, both named in the 21st century.

Bob Billings Parkway is the stretch of 15th Street west of Iowa Street. It borders the part of Lawrence that Billings is known for having developed: the former Alvamar Golf Club, now called the Jayhawk Club, and the surrounding neighborhoods. The Lawrence City Commission approved the renaming, which was proposed by the Lawrence Home Builders Association in 2004, a few months after Billings’ death.

Renaming an existing street was an unprecedented move in Lawrence, and it required replacing more than 50 street signs and changing a large number of addresses for homes and businesses with the Post Office.

George Williams Way, which runs north-south in western Lawrence and is the street that leads to Rock Chalk Park, is named for longtime City of Lawrence Public Works Director George Williams, who died in 2015. Williams was born in Lawrence, attended KU and worked for the city’s Public Works department for 45 years, culminating his career as its director.

Parks in Lawrence that bestow honor on people tend to be named in two categories: longtime city employees like Jim McSwain and Fred DeVictor, and recreational sports coaches who made an impact on youth and citizens of Lawrence like Louie Holcom L. R. “Dad” Perry and Elgin Woody.

Jim McSwain Park, at 1941 Haskell Avenue, was named for the longtime fire chief and also dedicated to honoring all firefighters. The 5-acre park is adjacent to the city’s fire training facility and had long been planned to be named in some way that would honor firefighters. McSwain was fire chief in Lawrence for 27 years, a job whose typical tenure is about five years. He had a background in fire training and oversaw notable fires fought in Lawrence, including the 1991 Hoch Auditorium fire on the KU campus and a 1997 Downtown Lawrence fire that damaged Sunflower bike shop but mercifully was contained.

“He did a lot for the city and had a big impact on shaping what is there today,” Parks and Rec’s Hecker says.

DeVictor Park, at 1100 George Williams Way, was dedicated to Fred DeVictor as he retired from directing the Lawrence Parks and Recreation Department in 2007. The city purchased the land for the 40-acre park from Alvamar Inc. in 1998.

“He developed the parks system in Lawrence. Where he started and where he ended is amazing,” Hecker says.

Louie Holcom was a community baseball coach and youth advocate, and Holcom Park, Holcom Park Recreation Center and Holcom Park Sports Complex, at 2700 W. 27th Street and 2601 W. 25th Street, are named for him. The sports complex was dedicated in 1974, and the park was established in 1976. The recreation center, which is 19,000 square feet, was financed through a bond issue and private funding in 1985 and 1986.

Dad Perry Park, at 1200 Monterey Way, was named in honor of L.R. “Dad” Perry, who was a teacher and coach in the Lawrence School District, and made an impact statewide, becoming known as the “father of gymnastics in the state of Kansas.” The city purchased the park in 1967 with matching funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Woody Park, at 201 Maine St., was named to recognize Elgin Woody, a Lawrence citizen who organized minority baseball and softball leagues for Lawrence youth. The park is located in the same area where Woody’s teams played, 4 acres purchased in 1936. p

![]()