The split between east and west started early in Lawrence, and East Lawrence has transformed into an artistic, eclectic part of town.

Monica Cliff (right) painting her mural at the corner of 11th and Pennsylvania Streets with her assistant.

Gardens across East Lawrence were bursting with flowers in May, but none were more intriguing than those painted by Mona Cliff, a multidisciplinary visual artist creating a mural near the corner of 11th and Pennsylvania streets.

A chokecherry’s white plume, the purplish-red swirl of a pawpaw blossom and the amethyst petals of timpsila, also called wild prairie turnip, are among the indigenous species featured in Natives NOW, Cliff’s contribution to the Rebuilding East Ninth Street Together arts initiative.

Each plant is painted on a panel; more panels spell “people” in the Osage Nation’s orthography to complete the mural. Cliff also planted those once-staple foods along the Burroughs Creek Trail & Linear Park, near 12th and Oregon streets, but her project isn’t about food. It’s about honoring the Native Americans who once populated the Kansas plains and those who now call Lawrence home.

“The core theme of my project is bringing visibility to our native community and representing our community,” Cliff explains.

It’s fitting that Cliff’s project is in East Lawrence, which has been a distinct neighborhood since Lawrence’s founding in 1854. Racially diverse and working class, residents welcomed newcomers, including African Americans and Mexican railroad workers, even as they suffered from discrimination and poverty. Recognition of that past is essential to understanding Lawrence’s potential, historians agree.

“Without East Lawrence and its people, the story of settlement, town building and stability in Lawrence would be incomplete and misleading,” Dale E. Nimz wrote in an essay published in Embattled Lawrence: Conflict and Community, a collection edited by Dennis Domer and Barbara Watkins.

Phil Collison works his plot in the community garden. A large number of delivery wagons with drivers and teams of horses in an open space near the Santa Fe railroad in east Lawrence – Douglas County Historical Society, Watkins Museum of History

Split From the Beginning

Lawrence was immediately bedeviled by an east-west split when settlers arrived at the previously surveyed site to find squatters had already claimed land east of what was to become Massachusetts Street. The dispute was eventually resolved, but the divide remained.

Sometimes “East Lawrence feels under attack, but that began in 1854,” Domer said in an interview. The architectural historian is now working on a new three-volume edition of Embattled Lawrence, which was originally published in 2001.

East Lawrence grew rapidly, in part because it was within easy walking distance of railroad and manufacturing jobs, churches, shops and social centers. Still, it was disparaged as “The Bottoms” because of its low-lying position next to the Kansas River, and land there was worth less than elsewhere.

Residents—mostly German Americans, African Americans and arrivals from states in the Middle West and Upper South—didn’t fit the New England image promulgated by Lawrence’s founders. Newspapers and politicians fretted over pockets of blight that, by the 1900s, were rife with illegal liquor, gambling and prostitution.

“East Lawrence was the side of town people didn’t go to—except they did go there for drinking and carousing,” says Phil Collison, president of the East Lawrence Neighborhood Association (ELNA).

Over time, East Lawrence fell into what Embattled Lawrence called “a cycle of decay and abandonment.” Aging houses and high rental occupancy made it a target for redevelopment plans in the 1970s and 1980s, including one for a trafficway along its northern boundary that residents rebuffed. A slow renewal has since been underway, to the point where gentrification has become the worry. That’s spurred community activism, and residents work to help shape East Lawrence’s future.

“We’ve had a strong sense of self and of who we are,” Collison says. “We focus on making our neighborhood a better place.”

Cody Marshall stands in front of the archway leading into the Haskell Indian Nations University Stadium

Native American Representation

East Lawrence has in recent decades taken on an artistic, eclectic vibe. That got a boost in 2013, when the city created a cultural arts district that overlays most of the neighborhood. A string of former industrial properties on Pennsylvania Street have been redeveloped as the Warehouse Arts District, and studios, galleries, a brewery and restaurants have all opened.

Public art has also increased thanks in part to Rebuilding East Ninth Street Together, which began in 2014, when the Lawrence Arts Center received a $500,000 grant from ArtPlace America. The ELNA is also a partner. Artists selected for grants, including Cliff, celebrate the food, stories, families, art and music of East Lawrence.

Cliff’s mural focuses on the Osage Nation because of its history in Kansas and because her husband and children are among its members. She herself is A’ananin/Assinaboine. But elements of Cliff’s images are familiar to many tribes, such as the ribbons that evoke ribbon skirts worn by indigenous women and floral patterns similar to those of scarves worn with traditional regalia.

Current social distancing because of the COVID-19 pandemic means some elements of Cliff’s project are on hold, including public benches and Final Friday events projecting Native American images. Yet it still presents a powerful message.

“It’s important to have somebody represent us so we can see ourselves in the community,” Cliff says. “We don’t always see that.”

One familiar Native American landmark is Haskell Indian Nations University. It opened in 1884 as a boarding school and served as a high school, post-secondary vocational education school and junior college before becoming a four-year university. Haskell is now a leader in indigenous education and a source of pride for the hundreds of Native American and Alaska Native tribes whose members have studied or worked there.

“That makes Lawrence the most tribally diverse place in North America at any one time,” explains Cody Marshall, a professor in Haskell’s Indigenous and American Indian Studies Department, who belongs to the Akimel O’odham, Piipaash and Hunkpapa Lakota tribes.

While Haskell is too far south to be considered part of East Lawrence, there is a connection. Completion of the Burroughs Creek Trail broke what Marshall calls the “invisible barrier” of 23rd Street by linking Haskell to other neighborhoods. That’s a boon for the students, faculty and staff such as Marshall who live in East Lawrence and cherish its character.

“There’s a certain community spirit that exists in East Lawrence that’s very close to being aligned with the indigenous way of connecting with people,” he says.

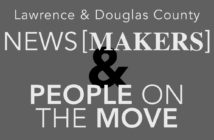

Reverend Verdell Taylor stands outside the St. Luke African Methodist Episcopal Church at 9th and New York streets.

Feeling History in Your Bones

Connection is also what makes East Lawrence unique to Verdell Taylor, pastor of the St. Luke African Methodist Episcopal Church, at 9th and New York streets.

“The feeling of this community is so special,” Taylor says. “There are still people looking out for one another.”

St. Luke AME Church was founded in Lawrence in 1862, just two years after Kansas passed an antislavery constitution and African Americans—both escaped slaves and freed people—made their way to the state. The Exoduster movement of 1879 brought even more to Douglas County, and many settled in East Lawrence.

By the turn of the century, African Americans owned grocery stores, hotels, blacksmith shops, bakeries and other businesses in Lawrence, and had established mutual aid societies, masonic lodges, women’s clubs and churches, Embattled Lawrence explains.

In 1910, St. Luke AME Church replaced its first wooden building with a brick version built in the Gothic Revival ecclesiastical style. It’s the church Langston Hughes attended as a child, where activists met during the civil rights movement and where about 100 members still belong today.

“It’s a different kind of history here,” Taylor says of the building, which is on the National Register of Historic Places. “It’s something you can feel in your blood, in your bones.”

Sadly, some of that history is heart-wrenching. Three men were lynched in Lawrence in 1882, and the 1920s brought Ku Klux Klan rallies to South Park. Jim Crow laws enforced segregation, and racism ran deep, says Bill Tuttle, a professor emeritus at the University of Kansas (KU) who has long studied and written about race.

“Most people don’t see Lawrence’s history this way at all,” he explains. “They take comfort from Bleeding Kansas and John Brown. That was a glorious history, but it didn’t last long.”

Racial tension escalated through the 1960s as African Americans and their supporters pressed for change in Lawrence’s schools, recreational facilities and businesses. At KU, students embraced Black Power and started the Black Student Union. Afro-House opened on Rhode Island Street in East Lawrence and served as a focal point for activism.

By 1970, Lawrence was reeling from protests, a curfew and fire bombings, including a fire that destroyed KU’s Memorial Union. Then, on July 16, police killed a young black man named Rick “Tiger” Dowdell. Four days later, a police officer shot Nick Rice, who was white. The city grappled with their deaths while at the same time struggling to come to terms with the Vietnam War, women’s liberation, counterculture and other issues.

“For better or worse, this sixties experience has shaped Lawrence,” historian Rusty Monhollon wrote in Embattled Lawrence.

Through it all, St. Luke AME Church was there for the community.

“By no means did people go through these things without the heartache and the pain,” Taylor says. “St. Luke was at the center of many things back in the beginning, but it still feels the pain and hardship that people today continue to go through.”

The church at the time of publication is closed because of a statewide stay-at-home order, and Taylor looks forward to when services can resume, as well as the Boy Scout, Lawrence Preservation Alliance and other meetings typically held there. For now, he remains engaged in the community as much as possible.

“The feeling that you get in East Lawrence, which, for me, is different than the other segments of the community, is that it’s calling you to be involved,” he says.

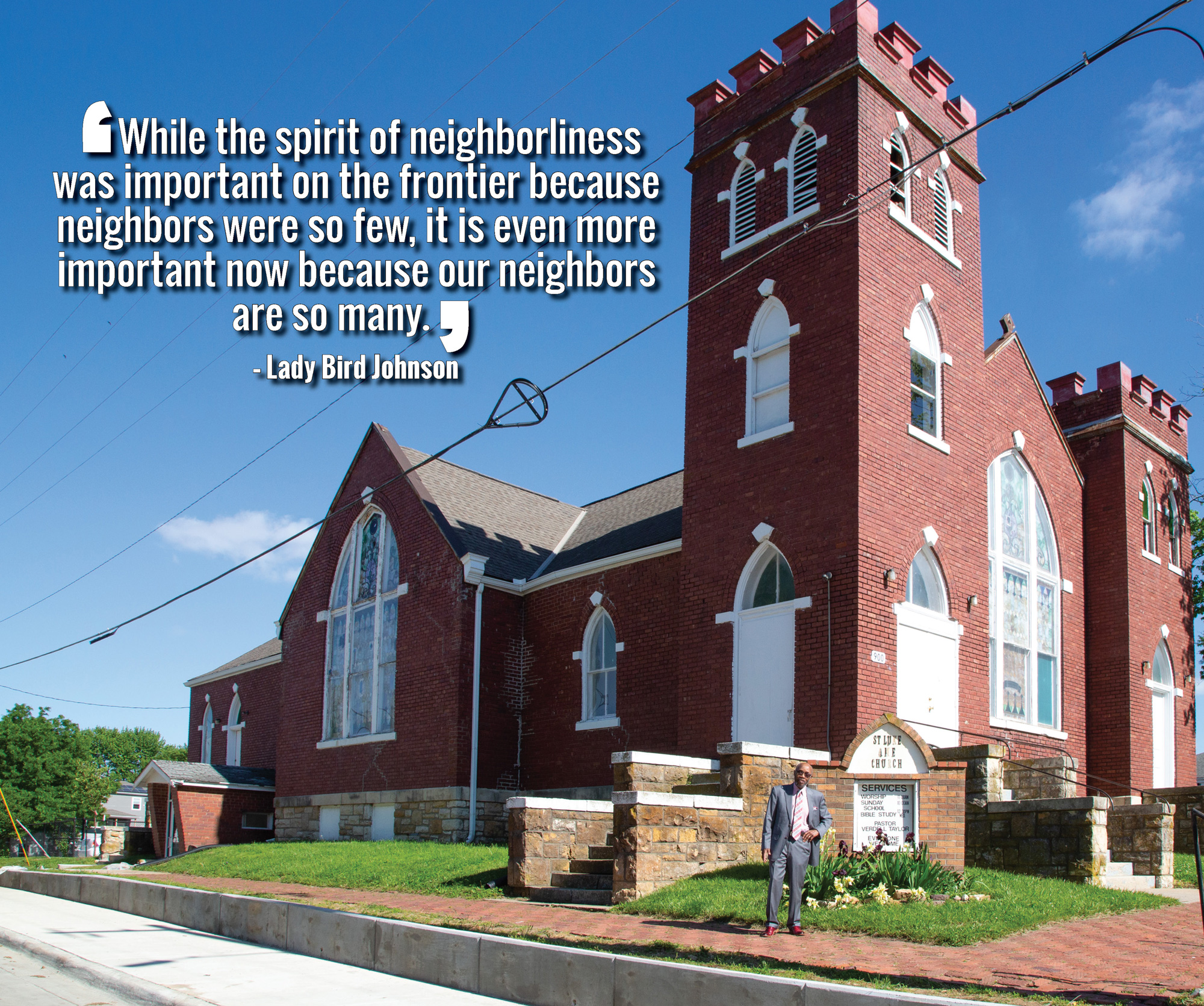

Brenna A. Buchanan Young and Dennis Domer out for a walk along the railroad tracks in east Lawrence.

Pedro “Pete” Romero stands on the train plat-form at the Amtrak train station.

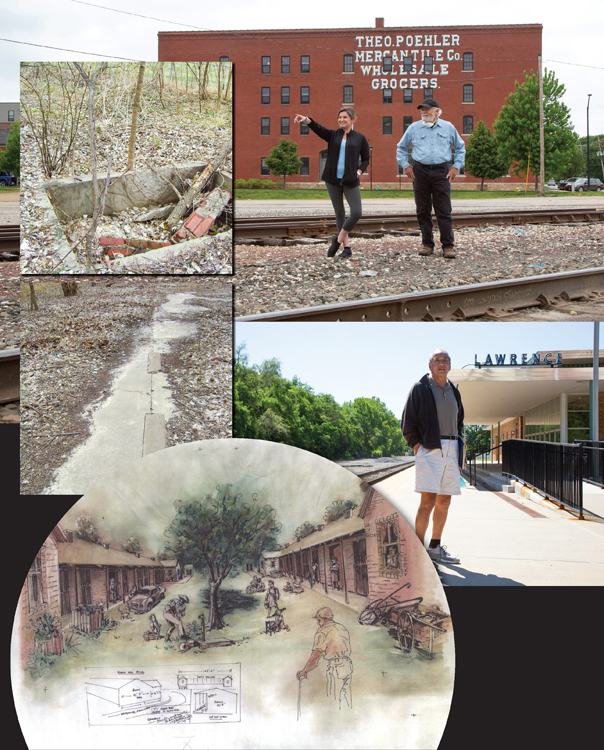

Photos of what remains of the foundation at La Yards and an artist’s rendition of the La Yarda buildings courtesy of Brenna A. Buchanan Young Douglas County Historical Society, Watkins Museum of History

Remembering La Yarda

Certainly, Brenna Buchanan Young felt that pull back in 2009, when she was an architecture student at KU. Young was helping Dennis Domer complete an architectural survey of East Lawrence when they met artist and activist K.T. Walsh.

“K.T. Walsh said, ‘I really need to show you something,’” recalls Young, who is now an architectural historian in Lawrence.

Walsh took them east to an overgrown spot between the railroad tracks and the river. There, she pointed out the remains of La Yarda, a housing complex built by the Atchison, Topeka and Sante Fe Railway in 1924 for Mexican railroad workers and their families.

It wasn’t entirely unique. Immigration from Mexico swelled in the early 20th century, and by 1930, Mexicans were the second biggest ethnic group in Kansas, according to the Mexican American Studies and Research Center at the University of Arizona. Many worked for the railroad, and

“It was just the closeness of the people,” remembers Pedro “Pete” Romero, whose family lived at La Yarda. “People were so willing to help each other. It was great.”

The complex had two long rows of housing units facing each other, with a stretch of grass in between and a single pump that supplied city water, Romero says. Men worked for the railroad and tended a large garden while women cooked, cleaned and cared for the children.

The kids liked walking into town to play with cousins or visit the row of warehouses near 8th and Pennsylvania streets, especially on Wednesdays. That’s when TNT Popcorn, a division of the Barteldes Seed Co., popped test batches of kernels and gave the popcorn to the kids, Romero explains.

“People were friendly,” he says. “It didn’t matter if you were Hispanic or black or white.”

River flooding was a constant threat to La Yarda, and Romero’s family moved to a house on New Jersey Street after the Great Flood of 1951 finally destroyed the complex. Decades later, he and a friend returned to La Yarda to measure the foundations and document its layout.

He also collected family photos from friends, and many were used in an exhibit created by the Watkins Community Museum of History. Young assisted with research. That part of Lawrence’s history was almost lost, but Romero hopes the city will dedicate a landmark to La Yarda so that never happens again.

“It’s a rich, rich history of the people who lived at La Yarda and struggled to make a better life for themselves,” Romero says. “We need our young kids to remember their grandmas and grandpas, and where they used to live.”

The same could be said for all of East Lawrence. For, as Dennis Domer puts it, the past is prologue. Understanding the neighborhood’s complex history is the key to helping Lawrence better appreciate its modern character and celebrate its potential.