Behind the scenes, technical theater professionals are the ones who bring the entire production to life.

| 2019 Q2 | story by Emily Mulligan | photos by Steven Hertzog

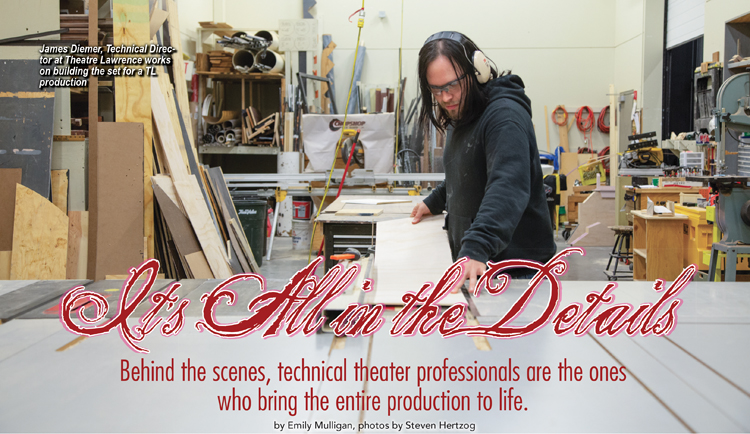

James Diemer, Technical Direc¬tor at Theatre Lawrence works on building the set for a TL production

Yes, actors and spotlights and sound are critical elements of any live theater production—after all, they command our attention most directly from the opening moments. But the costume details, the variety of scenery, the colors of the lights and the clever props all make audiences feel and sense the story, characters and setting, even on a subconscious level. It is that ethereal experience that people who work in technical theater, or “behind the scenes,” specialize in creating.

In addition to being mostly physical in nature, theater jobs do not keep normal workweek hours. Even when working behind the scenes and creating the scenes, technical theater professionals work a lot of evenings and weekends at rehearsals and performances. Along with the physical energy required to pull off a performance, technical theater professionals must possess almost endless creative energy.

Four local technical theater professionals—two from The University of Kansas’s (KU) University Theatre and two from Theatre Lawrence—illuminate the process by which they craft the story through scenery design, lighting, props and painting. Rana Esfandiary is visiting assistant professor of scenography for KU Theatre, where she designs sets for the University Theatre’s productions. Ann Sitzman is theater technical coordinator for KU and designs lighting for productions. Mary Ann Saunders is Vintage Players director and does set and scenic painting, as well as hair/wig styling for Theatre Lawrence. Marilyn Brobst is the volunteer props mistress who finds or makes all of the props for Theatre Lawrence.

Top to Bottom: Marilyn Brobst, “Props Mistress” at TL Mary Ann Saunders, “Master Set Painter” and assists with hair & makeup for TL Ann Sitzman, Lighting and Set Designer at the KU Theatre department Rana Esfandiary, Director and Set Designer at the KU Theatre department

For all four, the process for any given show begins with reading the play. Esfandiary and Sitzman say their first read-through is to take in and digest the story as a whole, barely beginning to visualize how it might look on the stage. Saunders and Brobst have a more fine-toothed comb approach to the first reading: Saunders looks for specific mentions of colors and hairstyles in the scenes, and Brobst highlights every mention of a particular item that will be needed as a prop. Esfandiary and Sitzman typically do a full second read-through to search for specific references and stage directions they will need to incorporate into their designs.

“When I’m reading a play, I’m thinking about each character. I think about how they are seeing their houses and the world they live in,” Esfandiary says. “I always go inside out. I see the world from inside the character’s mind rather than from the audience at first.”

Once they have an understanding of the story and characters, the collaborative process of theater begins. They meet with the director to understand what his or her vision is for this particular version of the play. Questions like time period and place are usually at the forefront of these meetings, as well as any story points or characters the director might want to highlight, especially to achieve a certain feel for the play on the Lawrence stage.

“When you have a really good collaboration between designers and directors, it is so rewarding. We can maybe affect people’s lives with the show, which is what theater is all about,” Sitzman says. “What is it that is going to make the audience walk away feeling something? What can I do to make this story more encompassing for the audience?”

After meeting with the director, the next step is research. Esfandiary may need to study a particular style of architecture or landscape design. Sitzman spends time researching the lighting colors that will evoke the desired emotion and setting of each scene, and the lighting angles that will best help achieve those emotions. Brobst researches time periods and what the characters’ possessions should look like from that time, whether she will retrieve something from Theatre Lawrence’s shop or create it herself. Saunders looks into what colors would have been found on the walls, floors and furniture of that era, and calls on her knowledge of colors to evoke the mood of the show, whether it’s a comedy, drama or musical, or any combination thereof.

“We have to understand the play, the audiences and the community. These affect the design so much. We think about the show architecturally, politically, psychologically, socially. At some point, we have to stop ourselves,” Esfandiary says.

Once the designers are armed with their research and the director’s plans for the show, they can begin creating. For Saunders and Brobst, creating is a hands-on process. They start by taking an inventory of what the well-stocked Theatre Lawrence shop has for paint colors, pieces and props. What doesn’t exist, they typically make themselves.

Instead of purchasing expensive wood, Saunders uses color and texture to create wood grains, such as the large “wood” floor she painted for the recent production of “Lend Me a Tenor.” She also paints walls to look like wallpaper and gives walls and floors a vintage or well-worn look, as needed. As for hairstyling, which she learned in college from a former boyfriend who was a stylist, she draws on the theater’s wig collection and experiments to create looks that match the time period. She is also careful to choose wig colors that complement the actor’s costumes and natural complexion.

Theatre Lawrence actors put on their make up at the final dress rehearsal for Lend Me A Tenor.

“I don’t know what it is, but I think color is my strongest visual aptitude. If I look at the set and know what the show is about, I use my color instincts to decide,” Saunders says.

Brobst can reuse furniture from previous productions—often with a painted facelift from Saunders—and many items like candleholders and plastic dishes also carry over well. Some of her biggest challenges, and hence most creative moments, come from food and the natural world. “Church Basement Ladies” from 2017 required meatballs. Using real food is impractical for many reasons, so Brobst fashioned “meatballs” out of sawdust, glue and paint. In “Little Mermaid,” the jellyfish needed to dance under the sea, so she made jellyfish puppets out of clear umbrellas, pink bubble wrap and lights. Conceptualizing props that are both eye-catching and practical is challenging.

“I sometimes don’t sleep at night because I have a lot of ideas going around in my head,” she says.

For Esfandiary and Sitzman, designing the sets and lighting involve employing theater-specific computer software to create accurate renderings.

“Renderings are labors of love for me. They help me figure out what I’m trying to achieve and exactly what I’m thinking,” Sitzman says.

Esfandiary sketches her concept using the Cinema 4D program, which presents a 360-degree picture for the director. Once the design is approved and she reconciles it with the budget, she builds a physical model of the set. “The model helps me understand my sketch better,” she says. She then does all of the drafting for the shop of how the set will be built, piece by piece, and then construction begins. Communication is a continuous two-way flow between the designer and the director as the set takes shape. “When we design something, we tell the director what the limitations are for blocking the show. We also plan entrances and exits to and from the stage through the set,” Esfandiary continues.

For each show she designs, Sitzman must design the lights with angles, colors and textures; hang the lights; focus the lights; then cue the lights during the actual show. To design the lights, she uses the scene renderings to create lighting renderings in Photoshop for the director and other designers. Then begins a series of paperwork to track information such as where each light is hung, electrical grids and number assignments for lights on the light board. The “magic sheet” is the final piece of paperwork, and it is a visual representation of every light system and how each light is focused to the stage. The lights are ready to focus once they are hung, circuited and patched—as the master electrician, Sitzman does all of this herself. “Lighting can either destroy the set and the costumes, or make it come alive. The audience may not realize it’s happening, but they’ll see it, and they’re going to feel it,” she says.

Top to bottom: Bob Newton, Sound Designer and a member of the TL Board of Directors, mics up Julia Peterson, one of the leads in “Lend Me A Tenor”. Terrance McKerrs, Director for “Lend Me A Tenor” Sherri Soule, volunteer Sound Operator and a member of the TL Board of Directors.

Top to bottom: Bob Newton, Sound Designer and a member of the TL Board of Directors, mics up Julia Peterson, one of the leads in “Lend Me A Tenor”. Terrance McKerrs, Director for “Lend Me A Tenor” Sherri Soule, volunteer Sound Operator and a member of the TL Board of Directors.

The designers see their vision and their world of the show come together before the actors take the stage at tech rehearsals. As visual experts, they feel like they already live in the story, and the actors are sharing in it, much like the audience does.

“Theater is a lot of collaboration to come up with the end product that supports the play. I think that theater is the ultimate team sport. We need to be able to work together to produce this thing that we feel like is living, and it’s the show,” Saunders says.

They all hope the audience’s memories from and experiences with the show last long beyond the final curtain.

“I have learned that we should not underestimate our audiences. We try to make the show open up a discussion about the issues of society and try to have a conversation with the audience instead of teaching them,” Esfandiary says.

Saunders says people who do not work in theater, especially behind the scenes, have no point of reference for all of the effort, teamwork and creativity that come together to make a show happen.

“Some people think we just order a set shipped in for each show and put it together. That is not at all how we do it. Everything is done in-house. We build it, paint it and make the doors work. We all do what we do because we love doing it,” Saunders says.

The hours are less than ideal, and they don’t get to be the ones standing on the stage accepting the ovations; yet these designers are passionate about what they do.

“I decided early on that this makes me happy in a way nothing else does,” Sitzman says. “It is ephemeral in nature; shows only last a certain amount of time. Every show is different and has its own life and own characters. It moves me.”

The actors aren’t the only ones who have strong emotions when the curtain rises to open the show.

Esfandiary says, “It’s magical for me when I see my work in the theater. It’s goose bumps.”