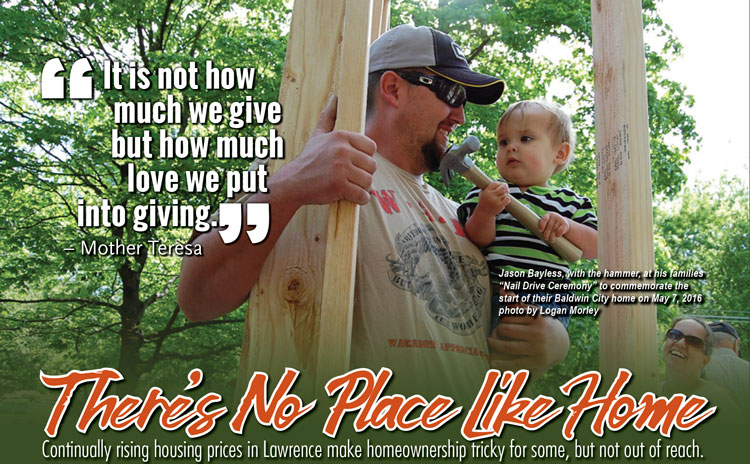

Continually rising housing prices in Lawrence make homeownership tricky for some, but not out of reach.

| 2018 Q3 | story by Bob Luder | photos by Steven Hertzog

Jason Bayless, with the hammer, at his families “Nail Drive Ceremony”; photo by Logan Morley

The pride beaming from Bobbi Reid’s voice is palpable when she talks about the two-story, three-bedroom townhome she purchased and recently moved into in Lawrence.

It was a life milestone she wasn’t sure she’d ever approach, let alone reach. A data entry/lead trainer for a document imaging company in North Lawrence and single mother of two teenage daughters, Reid’s finances were hit hard by a 2012 divorce, and she had been renting subsidized housing for much of the last 19 years. Homeownership seemed like a dream far out of her reach.

But, the memory of a loved one, as well as the love for her two daughters, kept the dream alive.

“In 2015, my fiancé passed away,” she says, with more fortitude and steeliness in her voice than yielding sadness. “I always told him that I wanted my own place. I wanted my kids to have a place they could call their own. That was a driving factor in me doing this.”

That drive prompted Reid to apply for a home purchase through the Lawrence chapter of Habitat for Humanity, not once but twice.

“Initially, I was turned down, so I tried again the next year,” she says. “September of last year, I received a call from a woman who was on the board. She asked, ‘Do you still want a house?’ I said, ‘Like yesterday.’

“I knew this was the only way I could ever own something,” she continues.

Habitat for Humanity, which has been in Lawrence nearly 30 years, is an organization perhaps best known for the high-profile involvement of former President Jimmy Carter that gathers volunteers and raises money to build and/or rehabilitate affordable housing for those in need.

It is just one of several affordable housing agencies in the Lawrence/Douglas County area.

The Lawrence Community Housing Trust—business name Tenants to Homeowners Inc.—uses subsidies from the federal government to sell affordable housing, which it either builds or rehabilitates from older houses or units.

The Lawrence-Douglas County Housing Authority was founded to build public housing with funding by the federal government but, today, has expanded its services to include jobs and children’s programs, among many other things.

Ask just about anyone, and they’ll tell you, as great a city as Lawrence is, it has one of the more difficult housing markets in the central U.S. Costs of homes have risen drastically, as they have around the rest of the country, yet much of the city’s employee force earns wages that place them in the low- to moderate-income categories. That’s made homeownership for many difficult to attain, much less maintain.

“It’s very hard in this town,” Reid says. “I didn’t want a handout. Habitat is huge in helping people. But, I still have to pay a mortgage. The loan is interest-free, which is awesome. But, I wasn’t gifted a house.”

That’s what all these agencies espouse in their missions, not to give free handouts but to allow the less fortunate opportunities to pull themselves up and establish independent and productive lives, for themselves and their families. This not only helps those directly affected but the Lawrence community as a whole, they say.

Shannon Oury, executive director Lawrence-Douglas Co. Housing Authority

Lawrence-Douglas County Housing Authority

The Lawrence Housing Authority was founded in 1968, merged with the Douglas County Housing Authority in 2001, and is celebrating its 50th year in 2018. Last year, it housed 2,743 Lawrence and Douglas County residents in 1,416 households. That included senior citizens (464), non-elderly disabled (451), families (501), children (993), home veterans (49) and formerly homeless (218).

Initially, the Housing Authority built affordable rental units using grant money from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Today, HUD no longer provides funding to build public housing but issues tax credits to build affordable housing for those who fall among low-income guidelines.

Rent for properties managed by the Housing Authority is income-based. Renters pay 30 percent of their income for rent. If they have zero income, a minimum rent is $50 per month.

According to the Housing Authority’s executive director, Shannon Oury, a recent housing study stated there was a need for 5,000 units in Lawrence for low-income people. Currently, the Housing Authority has 369 total units of public housing and manages a number of other units through various programs such as New Horizons, which tries to move families out of shelters, and City HOME and HOPE Building, which house the homeless, whether permanently or transitionally. The Housing Authority partnered with Bert Nash Community Mental Health Center and Douglas County to build 10 crisis center units for participants with serious, persistent mental illness.

Any way you add it up, it’s not enough to satisfy the need.

“We continue looking for opportunities to build more units,” Oury says. “The city has stepped up the last few years to address this issue.”

Oury says Lawrence passed a .05 percent sales tax last year earmarked for affordable housing, as well as formed the Kansas Housing Resource Corp.

What she’s perhaps most proud of, however, are the programs the Housing Authority has in place that go beyond simply putting roofs over heads. High on her list is the Move to Work (MTW) program, which encourages tenants to seek work and helps with education and employment services. The Full Circle Youth Program focuses on healthy lifestyles for the children in affordable housing and provides healthy meals and snacks. There are buses to help transport seniors to shopping areas, and the Lawrence Parks and Recreation Department hosts senior exercise sessions on-site.

“Our goal in the senior population is to allow them to age in place,” Oury says. “For families in the MTW program, the impact is really significant. One woman came to us as a single mother with no real skills. She left an LPN.”

Since 2012, the Housing Authority has partnered with Habitat for Humanity in a homebuyer match program.

“We remove barriers people have to upward mobility,” Oury says. “Last year, we had four people move out and buy their own home. This year, we’ve had seven.”

The Nard Family with Jereml Lewis and Rebecca Buford of Tenants to Home Owners

Lawrence Community Housing Trust—Tenants to Homeowners Inc.

The Lawrence Community Housing Trust endeavors to keep housing affordable with the help of federal and local subsidies. In its homeownership program, it receives a $50,000 subsidy that can only be used for affordable housing. The Housing Trust can then build a $150,000 house and sell it for $100,000.

“When you start with $50,000 to $60,000 for a lot, it’s hard to sell a house for less than $200,000,” says Rebecca Buford, executive director. “We can build a nice three-bedroom house for $120,000. If it’s $50,000 for the lot, $175,000 is reasonable.”

To date, the Housing Trust has built 96 new-construction homes and rehabilitated or acquired 61 homes for a total of 157 developed affordable houses. The Trust stewards 82 of those units, and all future homes it develops, in trust for perpetual affordability. Thus far, 385 low- and moderate-income families have stepped into first-time homeownership and have begun building equity while having stable housing.

“We are doing a good job of using (the funding) in our community,” Buford says. “All the money we get in trust, we restrict it and lock it into that house and into the Lawrence community.”

Buford says what she really loves about what the Housing Trust does is that it makes sure new homeowners are successful throughout their time in the house. Because the subsidy can be used as a down payment, buyers are not required to purchase mortgage insurance. All home buyers are mandated to put $25 per month into a maintenance account. If a buyer falls behind on mortgage payments, money from that maintenance account can be used to catch up.

“We’ve had zero foreclosures since 2005,” Buford says. “That’s in 130 transactions. If something happens, we find another eligible family to buy the house.”

The Housing Trust keeps general contractors on staff to make sure owners aren’t ripped off on bids by outside contractors. And, it builds each home with energy-efficient walls, windows and air-conditioning/heating units.

“If what you’re buying is $50,000 less than actual cost, you’re saving about $250 per month on your mortgage payment,” she says. “Energy efficiency goes hand in hand with affordability. We’re saving homeowners $150 per month in utilities.”

What most don’t realize, Buford says, is that her homeowners don’t consist of the unemployed and uneducated. They’re people who work jobs that simply don’t pay a wage high enough to afford the standard housing market in Lawrence. In fact, she says almost 40 percent of Lawrence households earn less than $35,000 per year and are eligible for her program.

“The impact to the community is so large,” she says. “The city is full of social workers, teachers, service providers … jobs that don’t pay a lot. This is a life-changer. We’re moving home buyers into the next step in life, build stability so kids can go to college, move on and be successful.”

Erika Zimmerman, executive director, Lawrence Habitat for Humanity at the Jeff Colter dedication

Habitat for Humanity

The Lawrence chapter of Habitat for Humanity was established in 1989 after local resident John Gingerich read a book by Habitat founder Millard Fuller, gathered a group of volunteers and raised $10,000 to build a single house on Harper Street.

This fall, the organization will begin construction on its 99th and 100th houses, says director Erika Zimmerman.

“That’s 100 families helped in 30 years,” Zimmerman says. “We’re very proud of that.”

Low-income families and individuals apply to Habitat for Humanity every January and are judged by three criteria, Zimmerman explains, need, ability to pay and willingness to partner. A family selection committee carefully weighs all different aspects of the application and makes a decision. How many families get selected is determined by what land Habitat has available and what funding resources are on hand.

Folks who purchase a Habitat house also must agree to a program the organization calls “sweat equity.” It is a mandatory requirement for each selected homeowner to invest a minimum of 200 hours of volunteer labor themselves, which can include hours spent in homeowner education classes, working at Habitat’s ReStore or helping build a Habitat home. The sweat-equity requirement also is looked at as the homeowner’s down payment on the home.

“Sweat equity also allows homeowners to get to know other Habitat homeowners as well as learn all of the things that go into building a home,” Zimmerman says. “When maintenance issues arise, the homeowner can be more confident in figuring out the issue and how to fix it.”

In 1991, Women Build was formed as part of Lawrence Habitat for Humanity as a program to encourage women in homeownership and the construction career field. It works in the community to raise money to build one home every other year and educates the community about the importance of shelter and homeownership. Thus far, it has raised money to build eight homes.

“Without the amazing women in Lawrence who fund-raise and promote the Women Build house each year, we wouldn’t have been able to build our house,” says Andy Brown, a Habitat for Humanity homeowner and Women Build’s most recent recipient. “It takes months of work and planning to raise the funds needed to build these houses and keep them affordable for families like mine. I can’t express enough gratitude for the work they do as volunteers.”

Though Habitat for Humanity does receive some funding from federal, state and local grants, a big portion of building dollars is raised privately through campaigns, events and relationship building.

“The philanthropic spirit is how Lawrence Habitat began and is how it keeps going after all these years,” Zimmerman says.

Bobbi Reid and her two daughters

Another source of income for Habitat is the ReStore, which accepts donations of used home goods, recycles and repurposes them, and resells back to the public. The first ReStore was built years ago in Austin, Texas, and the one in Lawrence sits adjacent to the Habitat offices just east of downtown.

“We just started buying and rehabbing townhomes,” Zimmerman says. “For 2019, we have one townhome, one new build and 10 to 12 home-improvement projects.”

Zimmerman says she has one construction manager on staff, and Habitat pays subcontractors for things like foundation work, plumbing and electricity. All other work is performed by volunteers.

“That’s how we can build a five-bedroom home for $120,000,” she says.

Habitat also serves as banker in the transaction, overseeing the mortgage process with its homeowners. Mortgages are interest-free, and monthly payments are usually capped at 30 percent of income. Zimmerman says, thus far, 40 of 98 houses have been paid in full or sold.

Bobbi Reid hopes to join that list in about 25 years. She and her two daughters moved into their townhome in early July, allowing them to be independent and secure in ways they hadn’t known in quite some time, perhaps ever.

“Had this not happened, I don’t know where we’d be right now,” Reid says. “We probably wouldn’t be in Lawrence anymore.

“I wanted to stay here. It’s the only place my daughters have ever known. If not for Habitat for Humanity, this would’ve never happened. We would not be here. It’s the best thing I’ve ever done,” she says.