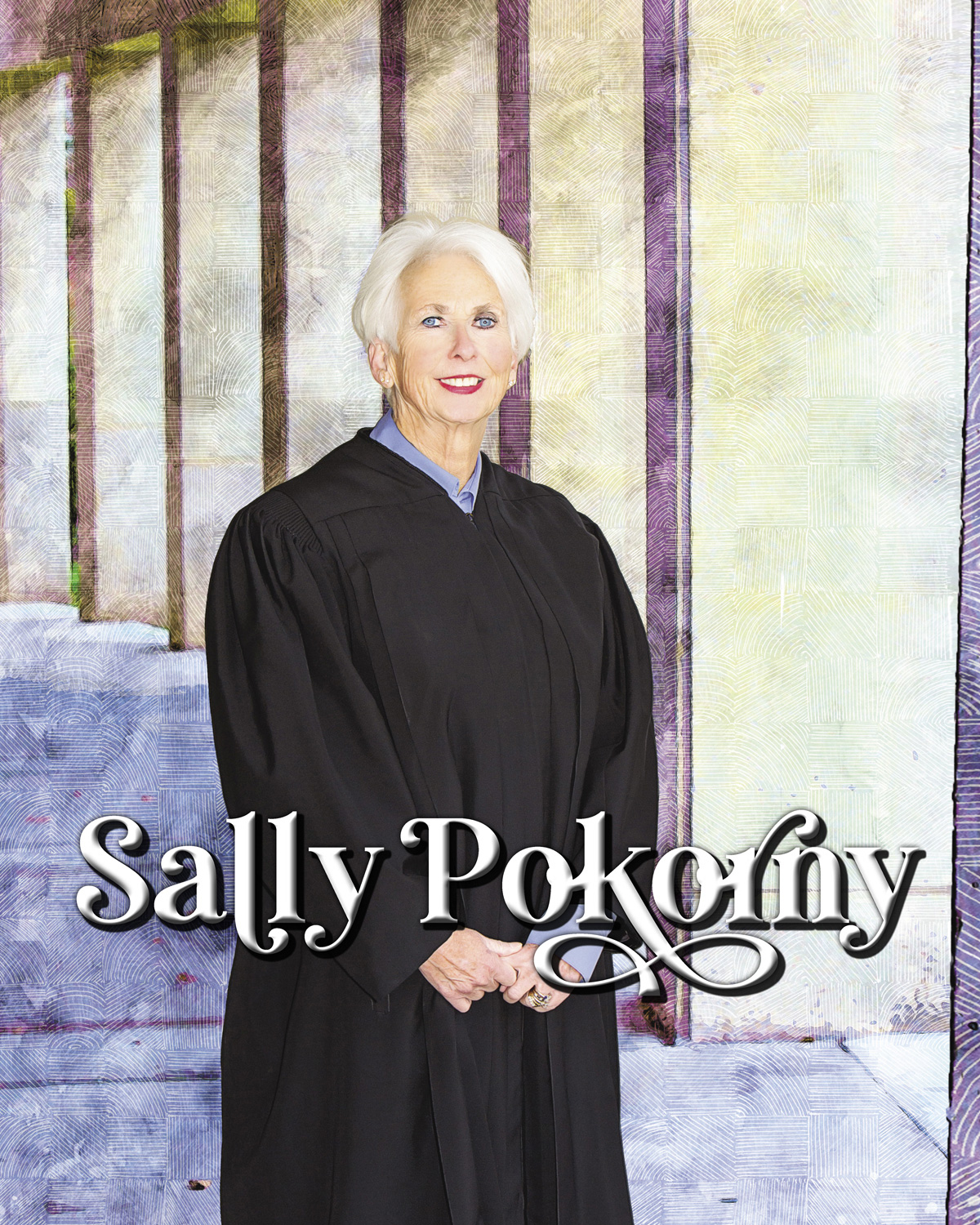

| story by | |

| photo by | Steven Hertzog |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

Using fairness and reason while relying on a deep-rooted compassion, Judge Sally Pokorny presides over her courtroom much like she does her life—with an eye toward treating all people with humanity.

Sally Pokorny: Woman of Impact

Judging other people is generally not considered polite behavior. So most of us work to withhold our judgments and hold our tongues when it comes to commenting on the attributes and actions of others.

There are only a precious few for whom judging is actually a profession. As a society, we look to judges to guide us within the law and set expectations for how to behave in order to perpetuate a germane society. That influence and its ripple effects are gigantic for those who must enter courtrooms and face judges, and certainly for society at large, as well.

Judge Sally Pokorny has presided over her courtroom in Division II, at the District Court of Douglas County, Kansas, 7th Judicial District, since 2009. She hears primarily criminal cases, as well divorce and family law. From behind the bench and in the community, it is difficult to overstate the impact that Judge Pokorny has had on individuals’ lives and on local society.

She is known for her fairness and reason, but she is also known for empathy and continually striving for improvement in the law and law enforcement communities.

According to APursuitOfJustice.com, some of the qualities of a good judge are judicial temperament, an ability to communicate, suitability to the workload and courage and integrity. Pokorny transcends all of these attributes with her outward focus and forward-thinking, and with her kind heart.

Let’s present a profile of Judge Pokorny, as best we can—without judgment.

Judicial Temperament

Being fair and consistent in applying the law are at the core of what it means to be a judge. Day in and day out, people coming before Pokorny are accused of making big mistakes, physically harming other people and not honoring their marriages. It is fair to say that these people are not at their best, and in fact, many of them may be at their very worst when they are before her. The easier route might be to dismiss them as “bad people” or “criminals,” and move on to the next case.

“She is very cognizant of the fact that people screw up, and that doesn’t mean they’re not people,” says her longtime friend and fellow attorney, Sally Shattuck.

Pokorny strikes a balance between being a human being and also an authority figure.

“She’s only 5 feet tall, but when she is on the bench, she is in total control of that courtroom,” says Patti McCormick, another longtime friend.

For her part, Pokorny says she does not separate who she is or the experiences she has lived from those who appear in her courtroom, to the contrary.

“Being a woman plays a big role for me. My perspective on life is as a woman,” she says.

For example, she says when a couple divorces, it is a big financial hit for both of them. In a traditional marriage, the man typically recovers financially in three to five years; the woman rarely gets back to where she was before the divorce. So she bears that in mind as she helps determine support between the divorced couple.

Ability to Communicate

To be sure, Pokorny has written more than her fair share of legal briefs in her 40-plus-year legal career. She has honed her craft of written communication. She finds, though, that the most valuable communication taking place in her courtroom is the verbal variety—and not necessarily coming from her.

“I tell people to talk to me about why they came to this. No one has listened to them for a long time. Many people have been in jail so long that it’s the first time they’ve been sober for any amount of time and had full mental health treatment and medications,” she explains.

McCormick marvels at the impact Pokorny has on people in just the relative short amount of time their case is before her. They stay in touch with Pokorny and continue to send her letters with updates on their lives.

“Many people have told her that they always feel like they are getting a fair shake. She actually listens to them, she looks at them, she gives them time to tell their story,” McCormick says.

Suitability to the Workload

Being a judge—and before that, being an attorney—is demanding. Start just with the amount of reading that takes place: hundreds and thousands of pages of documents. Add to that daily and hourly courtroom arguments and dockets, plus being the “duty judge” to take calls 24/7 for one week every six weeks. And well, you have to be willing to work really hard.

Pokorny did not set out to be a judge. In fact, as a young girl, her goal was to become a gynecologist. She blames her astigmatism for causing her to break too many slides in the microscopes in high school science, though, so she chose a different path. After majoring in history education at Washburn University and doing her student teaching, becoming a teacher wasn’t the right fit either. At the time, she says, she was living in Topeka, across the street from Washburn Law School.

“I thought, I can delay my life for three years if I get into law school,” she says.

Pokorny’s first job in government law came during law school, when she received a grant from the U.S. Department of Justice to do a summer internship with the county attorney in her hometown of Independence, Kansas. She came back to Topeka and worked for the Shawnee County District Attorney while she was in law school and for three years total. She says she worked Shawnee County dockets as a jack-of-all-trades, from paternity cases and child support to consumer protection, to care and treatment cases for the mentally ill.

She moved back to Montgomery County from there and worked part-time for the County Attorney and part time with her own private practice. Then she ran for, and was elected as, Montgomery County’s first female county attorney. She served one term then returned to private practice so she could count on job security for supporting her young sons.

In 2006, Pokorny decided to move to northeast Kansas to live closer to her sons, who had both graduated from Washburn and decided to stay in the area. She went to work with Lawrence attorney David Brown in his private family law practice.

It was there that she saw how all of her prosecutorial experience had amounted to a potentially good fit for a judge position. So she threw her hat in the ring to become district judge and was appointed by then-governor Kathleen Sebelius.

“I think it was a really good time in her life to become a judge. She had been in practice for a while and had a desire to be able to change things in court,” Shattuck says.

Courage and Integrity

Having the courage to put on the black robe and sit in judgment of others is one thing. Having the courage to actively seek change in how justice is served to people is another.

Pokorny is one of the founding members of—and the judge for—the Behavioral Health Court (BHC) of Douglas County, the existence of which she credits largely to former District Attorney Charles Branson. The court, established in 2017, comprises mental health professionals, substance abuse professionals, peer support counselors, corrections officers and others in order to address the increasing number of defendants with mental illness in the court system.

“County jails and prisons are the largest mental health facilities—that’s where people get treated,” Pokorny says.

She is the presiding judge, but she emphasizes that the BHC is a team effort. She also says she thinks the BHC is one of the most impactful things she has done.

“What she has done with the Behavioral Health Court is remarkable, forward-thinking and very compassionate,” Shattuck says.

Douglas County’s BHC, which convenes weekly, has become a role model for other jurisdictions in Kansas and out of state, but McCormick says Pokorny helps make it more than just the sum of all its parts.

“Sally is the only one to talk in the Behavioral Health Court. She doesn’t wear her robe, she just sits up front with all the people. She really gets involved in their lives and is upset when they fail—and they do fail sometimes,” she adds.

A Whole Person

Trying to parse out every aspect of working as a judge is not as simple as separating the wheat from the chaff. Criminal judges have to be well-balanced people outside of the courtroom, as well, or the gravity of some of the defendants’ actions and the complications of the justice system can take a deep toll.

“To know Sally, you have to stand back and watch the magic and impact that she brings to her life and friends,” McCormick says. “She has friends from every phase of her life. I’ve never known anybody that has so many friends.”

Pokorny says she has become good at compartmentalizing some of the horrors of her job. She makes sure to seek relaxation and appreciate happy moments and occasions to help keep her upright.

“With Sally, what you see is what you get. She’s fun, she’s gracious, she’s welcoming, she’s smart,” Shattuck says.

Pokorny will continue to be a catalyst for change in her profession. Outside of the courtroom, she has been a leader in legal organizations at the state and local levels, and she helped found the Kansas Women Attorneys Association.

“She likes to take the practice of law and use it for the betterment of people,” McCormick says.