| story by | |

| photos by | Steven Hertzog |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

Projects related to water—drinking, wastewater, and stormwater—are abundant and costly in Lawrence, whether responding to a problem, making upgrades to the existing system, or planning for the future.

Water Tower near KU campus

Ask your average citizens to envision the city’s water infrastructure, and their mental image probably goes in one of two directions: either they picture a giant Roman aqueduct, or they recall a local crew on a street repairing a broken water main. The truth of the matter is most of us have no idea what the systems look like that transport our drinking water, wastewater and stormwater. And yet, we rely on those systems and use them every single day, sometimes every single hour.

Water infrastructure isn’t something constructed and interconnected, and then the water flows freely and perfectly for the next 50 or 100 years. If only.

The City of Lawrence staff in Municipal Services and Operations (MSO) has an almost infinite number of water-related infrastructure plans and projects underway on any given day. As you read this, someone is lowering a video camera into a storm sewer to document its condition for a long-range project; someone else is working on design for the upcoming $52-million upgrade to the Kansas River Wastewater Treatment Plant; and someone else might be about to dig to find the source of a leak using detailed information from the City’s mapping system, which tracks the type of pipe and soil in that spot.

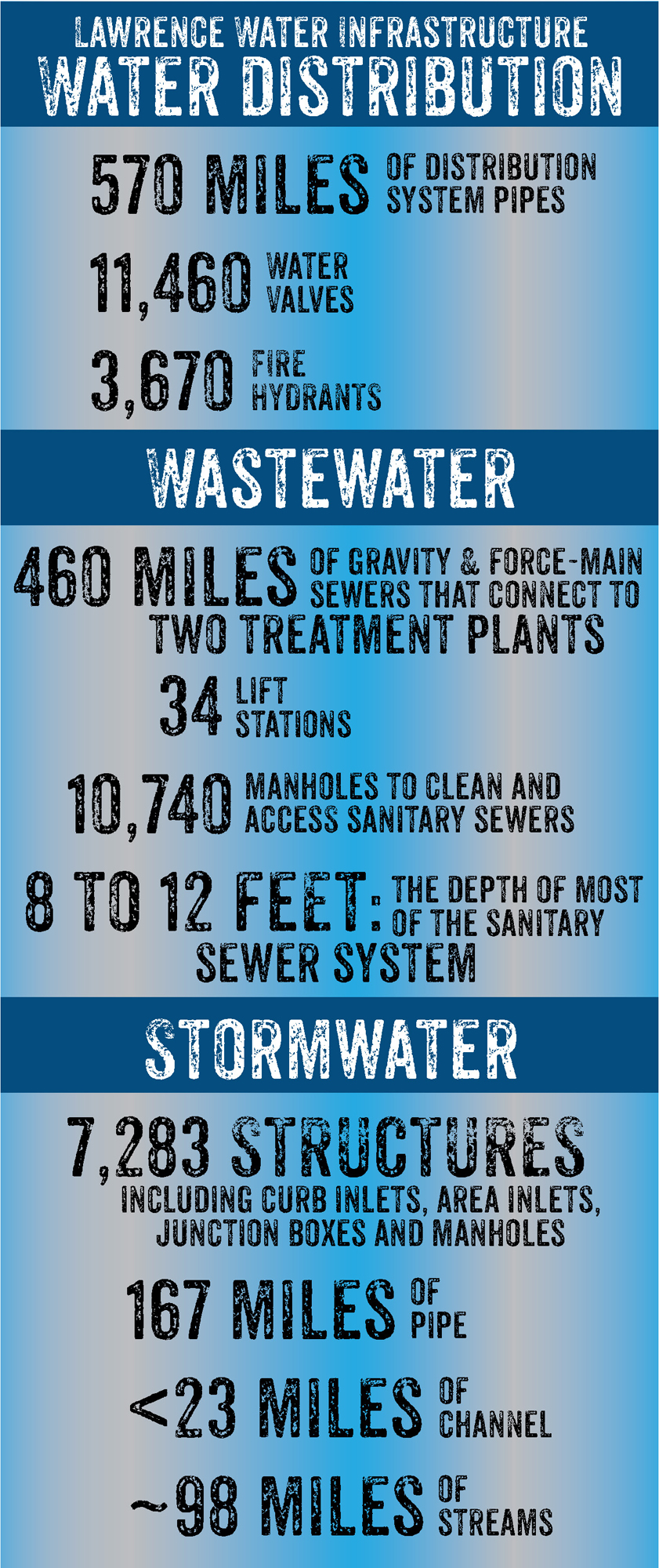

When talking about water infrastructure, it is important to note there are three different types of water systems that serve the City of Lawrence: drinking water, wastewater and stormwater.

Deputy Director Mike Lawless gives a tour of the Kaw River Water Treatment Plant to Jack Bell, owner of Turf Masters

Drinking Water Distribution

Lawrence is fortunate to have not one but two freshwater sources from which to draw water to drink: the Kansas River and Clinton Lake. The City operates two water-treatment plants: the Kaw River Water Treatment Plant, near Burcham Park, and the Clinton Reservoir Water Treatment Plant, at Clinton Lake.

The Kaw River plant is the older of the two, built in the 1910s and upgraded in 1955. “A new building and basins were constructed that upgraded the treatment process, but we are still working on that 1950s technology. We are rehabbing 65-year-old concrete basins on an ongoing basis as funding and continuous operations allows,” says Mike Lawless, deputy director of MSO.

The Clinton Reservoir plant was constructed in 1980, which makes the newer of the two plants already 40 years old. Lawless says it serves its purpose well. “But there are ongoing maintenance issues, no different than your house in a way. We have to maintain the roofs, HVAC, concrete, mechanical pumps and things like coatings on the tanks,” he says.

Besides the treatment plants, water-distribution infrastructure encompasses water towers, fire hydrants, water valves and hundreds of miles of water pipelines that deliver the water from treatment plants to residences and businesses. Those water mains and pipes range from 24 inches in diameter down to service lines that are ¾ inch in diameter. Depending on their age, they are made of concrete, PVC plastic, cast iron, transite, ductile iron, copper or galvanized steel.

Wastewater Treatment

Similarly to water distribution, the city has two wastewater-treatment plants, an older one and a newer one.

The Kansas River Wastewater Treatment Plant, on East Eighth Street, east of the Warehouse Arts District, was built in the 1950s. Major changes were made to the plant in the 1970s, Lawless explains, because of the Clean Water Act. In the early 2000s, the plant was adapted for some new processes. And now, 20 years later, the plant is about to undergo further upgrades that will change the way nitrogen and phosphorus are processed with biological nutrient removal.

The Wakarusa River Wastewater Treatment Plant, southeast of town on 41st Street, was completed in 2018. Wakarusa is a biological nutrient-removal plant, so once the Kansas River plant is upgraded, both plants will be capable of removing nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater.

Engineering Program Manager Matt Bond on the Kansas bridge overseeing the Bowersock Dam project

Directing Stormwater

Storm sewers and drains, like water lines and sanitary sewers, are under us and all around us. Most of the time, we are unaware of their existence, but there is nothing like a couple of inches of rainfall in the short span of an hour or two to show us where the drains and sewers are not up to task.

Matt Bond, engineering programming manager of MSO, often hops in his vehicle at the first sign of incoming heavy rain in order to see for himself how well the City’s stormwater infrastructure is or isn’t functioning.

“In 2019, we had five extreme rainfall events. In one of those, we received almost an inch in five minutes. In 2020, we had two or three of those events, and on April 28 of this year, the rain gauge at Pump Station 16, west of the Vermont Street bridge, recorded 2.17 inches of rain in 25 minutes,” he says.

Even without these extreme rains, certain streets and neighborhoods don’t shed water at an adequate rate. The stormwater infrastructure is best described by some of the projects that are underway to assess and repair it. Certain intersections fill with water during rainfall, which makes for dangerous driving; and water ponds in some grassy areas or people’s yards sometimes don’t drain for days after rain. Engineers work to pinpoint the choke points, where either the water can’t get to storm sewer inlets or where it doesn’t flow quickly enough once it does.

Bond began public meetings this fall to discuss the Jayhawk Watershed, which is a former open channel that ran from Mount Oread to the Kansas River, and now is underneath the area of Ninth and Indiana streets, toward Eighth and Ohio streets and northward. After detailing the entire watershed, he and his group found that those spots in particular are taking on water in storms.

“We can’t just add more curb inlets. We have to increase the size of the conduit to allow the water to flow,” Bond says.

He also has developing projects near 17th and Alabama streets south of KU and along Sharon Drive northwest of the former Hy-Vee on Sixth Street.

Water Challenges

By the Numbers

Many of the MSO’s projects are in response to a problem, whether an emergency or an ongoing known issue, such as the corrugated metal pipes that are only about 20 years old but are beginning to corrode in certain soils. Other projects are general system upgrades or in response to EPA rule changes—and some are even related to climate change.

The emergencies are one thing. With an onset of cold weather in the winter, there is no telling how the various mains and sewers will change and shift underground. Pipes, sanitary sewers and routing around Lawrence ranges in age from the late 1800s to shiny, new 2021. Every season is different and, in some ways, unpredictable; but at the same time, the City’s geographic information system (GIS) maps every water main, sanitary sewer line and storm sewer. The GIS reflects every repair plus the materials of the mains and sewers, and even the soil types throughout the city. Much of this information is available to the public, as well, on the interactive map featured on the City’s website.

“We have water infrastructure that’s really old that we have to take care of, and unfortunately, we have water infrastructure that is not that old that we have to care for,” Lawless explains.

Long-Range Water Infrastructure

In the past decade or so, the City has made a concerted effort to carry out more holistic, long-range projects involving water infrastructure. The ongoing EcoFlow project, which installs sump pumps in many homeowners’ basements in order to keep stormwater from affecting the sanitary sewers in certain neighborhoods, began about eight years ago and was one such project.

Planning, bidding and construction for the extensive upgrades at the Kansas River Wastewater Treatment Plant will likely extend until 2025.

In the meantime, the City is about to be the proud owner of thousands of new water service lines starting this month, thanks to a significant EPA rule change, the 2021 National Primary Drinking Water Regulations: Lead and Copper Rule Revisions. Related to the discovery of lead in the drinking water of Flint, Michigan, in the mid-2010s, this new EPA rule requires municipalities to be aware of what kinds of pipes are transporting drinking water right up to its residents’ dwellings.

Lawless says under previous rules, the City owned and maintained the service lines from the water main to a residence’s water meter. The length of the line that went from the water meter to the structure was to be maintained by the residence’s owner, but no longer. Now the city must maintain the water service line all the way from the water main up to the structure.

With more than 34,000 water meters in the city, the project’s scope will be unprecedented. Add to that the City does not know the materials or condition of the vast majority of those service lines—and many of those that have records are only documented on manual paper file cards—and this could amount to quite the undertaking.

“We don’t have very good information about the service line material that is between every meter and structure. The new rule says that we need to know that. In three years, we’ll have to tell the EPA what we know and what we don’t know. If we don’t know, the rule says we have to treat them as if they’re lead,” Lawless says.

Storm water engineers are in the midst of their own three-year inventory project, Bond explains. The asset identification program began earlier this year and involves taking 360-degree video of every single storm sewer and storm water asset that is more than 10 years old.

“We will assess the condition of all of our structures, and then we will build a capital-improvement program on that,” he says. “We anticipate we’re going to find some issues.”

Water indeed is everywhere in Lawrence, and where there is water, there is just as likely to be a plan to maintain, expand or improve its infrastructure.

“I think we do a pretty good job finding the balance between the funds we have and what needs to be done,” Lawless says. “I hope we’re doing a better job of trying to project what we need to do.” p

![]()