The Public Land Survey System was the U.S.’s solution to surveying and distributing land to settlers despite it having already been claimed by indigenous people.

Surveys of the public lands in Kansas and Nebraska Territories made it possible for settlers to claim land and establish legal title to it. Today, rural areas still use range, township, section and section subdivisions to describe property. Perhaps if you grew up on a farm, you heard phrases such as “the lower 40” or “the west 40,” referring to the 40-acre quadrants of a section. The massive mapping effort of the Public Land Survey System was one of the most important factors in making it possible for people to settle in Kansas.

Many of us recall learning about the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the size of the United States at that time, in high school history class. The United States purchased 530,000,000 acres of territory in 1803 for $15 million from France. Once the U.S. had acquired this vast, funnel-shaped area from the middle Canadian border, across the Great Plains and narrowing into the Mississippi River Delta, it had to figure out how to make it available to settlers. The solution was the Public Land Survey System (PLSS), which established a grid of townships, ranges and sections to create legal descriptions for specific parcels of land.

The statement that the U.S. purchased this land from France ignores the fact that much of the land was claimed by Native American tribes. Debates about the idea of indigenous lands rights resulted in numerous court cases lasting into the 1930s. The Indian Claims Commission was established in 1946 to determine historical damages for the loss of tribal land. The damages were estimated at over $800 million, 20 times what the U.S. had paid France in 1803.

Thomas Jefferson wanted to use the land acquired through the Louisiana Purchase to distribute to Revolutionary War soldiers and to raise money for the U.S. by selling it. To prepare for this distribution, the land had to be surveyed. On Aug. 26, 1854, the Commissioner of the General Land Office, John Wilson, provided instructions to John Calhoun, who had been appointed Surveyor General of Kansas and Nebraska. The first priority was to survey and mark the border between Kansas and Nebraska territories. Wilson wrote to Calhoun:

- For reasons of expediency, because of the apprehension of hostile interruptions from the Indians, it is not deemed proper and prudent to survey a base line further to the west than one hundred and eight miles distant from the Missouri River, at the precise point where it is intersected by the 40th parallel of north latitude.

LOCAL MATTERS

Our Local Advertisers – Making a Positive Impact

Calhoun, born in 1806 in Boston, moved to Springfield, Illinois, where he became a surveyor. He was a Democrat and supported Stephen A. Douglas, who proposed popular sovereignty that called for the residents of a territory to vote on whether to allow slavery in their proposed state. Douglas used his influence with U.S. Pres. Franklin Pierce to have Calhoun appointed Surveyor General of Kansas and Nebraska. He participated in the Lecompton Constitutional Convention in 1857 and was considered a moderated proslavery supporter because he supported a vote on the issue.

The contract for establishing the baseline between the Kansas and Nebraska territories was awarded to U.S. Deputy Surveyor John P. Johnson. He was not an experienced surveyor but began working to establish the baseline on Nov. 16, 1854, and finished 20 days later on Dec. 5. At the same time, Charles Manners and Joseph Ledlie were preparing to begin surveying in the territories. Manners was assigned Nebraska, and Ledlie was awarded a contract for Kansas.

Manners was to procure a cast-iron monument from St. Joseph, Missouri, and place it at the east end of the baseline on the western bluff of the Missouri River. This monument weighed approximately 600 pounds and was transported by canoe from St. Joseph and set by Charles Manners on May 8, 1855. Meanwhile, Ledlie realized the corner that Johnson set at the First Guide Meridian East was located incorrectly. They both returned to Leavenworth hoping to get instructions from Calhoun. On May 30, 1855, Ledlie wrote his brother to update him on his work.

- I came out to this country prepared to execute such contract, or contracts for surveying as I might be able to obtain from the Surveyor General. I have now in my employ ten men; two teams of mules and all necessary equipment for a regular camp siege. Mr. Charles A. Manners, late surveyor of Christian County, Ill., with a like number of hands is associated with me in the enterprise.

Both Ledlie and Manners found errors in Johnson’s work. Again, Ledlie wrote his brother about this problem.

- I arrived at my place of destination on the evening of the 8th. On the night of the 9th made the necessary observation of the Polar Star when on the eastern meridian and again when at its greatest eastern elongation thereby establishing very satisfactory a true meridian. I now felt pretty well contented and felt strongly in hopes I could be able to proceed next morning. The next morning I tested the baseline by the meridian thus found; and to my horror and astonishment found the base line wrong. … finally I concluded to start east on the line and meet Mr. M. I left my men in the camp (except one) and taking one of my lightest wagons I proceeded on east, and on the evening of the 13th met Mr. M 33½ miles from my camp; he was encamped on the waters of the Nemaha. … That night I established a true meridian at his camp with my transit instrument and the next day compared it with Mr. M.’s solar compass, and found to agree to a hair.

Ledlie and Manners decided they needed to report these problems to Calhoun, but he had already returned to Springfield, Illinois. The primary way of communicating with people in the east was via the telegraph. Calhoun did not respond to the first telegram the surveyors sent. Eventually, Calhoun responded that he was at home, and Ledlie sent him another message. It was unsuccessful because, “the next day, the lightning took possession of the wires, and we have not been able to obtain any answer to your dispatch as yet. On yesterday morning, we dispatched a special messenger to Springfield fearing that the wires would not be relied upon.”

The deputy surveyors were paid by the mile for surveying completed at the rate of $12. They created field notes to document their measurements. These were submitted to the Surveyor Generals office at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The employees staff included a chief clerk, a chief draftsman, draftsmen, copyists, clerks, accountant and messengers. Estimated expenses for this office of 1857 totaled $19,400. The surveyor general’s salary was $2,000, and six clerks, paid varying salaries, received a total of $7,400. The cost of transcribing field notes was estimated at $4,000 with another $6,600 for office rent, stationery and contingencies. Surveyors were paid by the contract with amounts ranging from approximately $500 to $700.

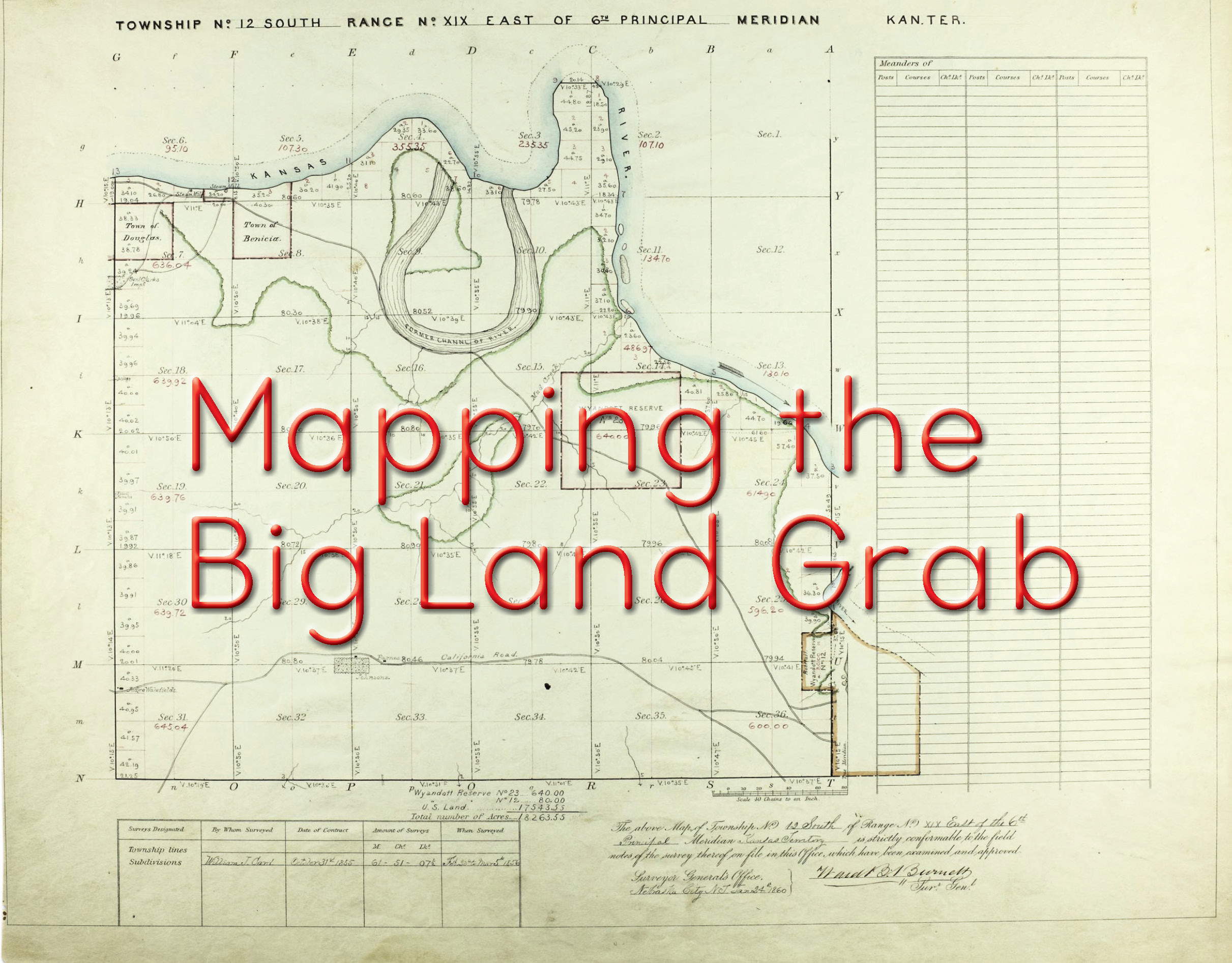

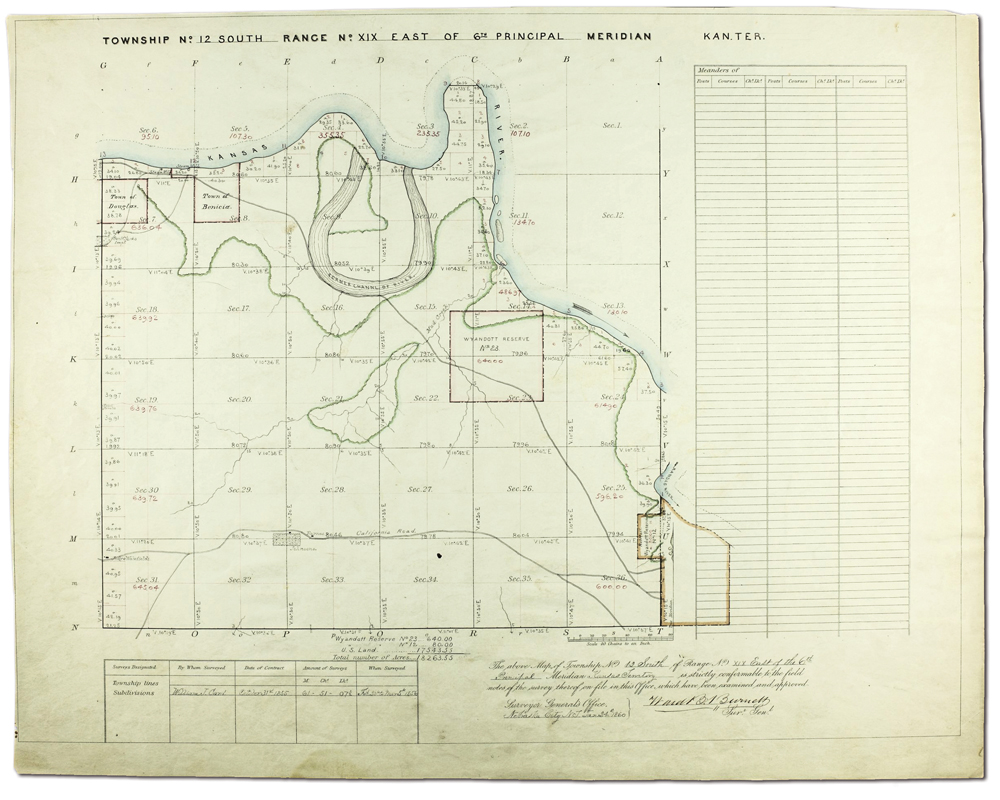

Plat maps from the work creating the Public Land Survey System were created by draftsmen using the field notes of the surveyors. They are close to “works of art” given the information with which the mapmakers had to work. The key to the maps follows: Green outline of banks and riparian areas around the streams, rivers were drawn in blue, squares with squiggly lines across them are cultivated lands, roads and trails consisted of two parallel lines, and the exact acreage of each section is shown. The map show is for a plat for Township 12 S, Range 19 E which ultimately contained part of Lawrence.