| story by | |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

Local environmental nonprofits and research centers are valuable commodities when it comes to community outreach and research, as well as a boon to the economy.

Local environmental nonprofits and research centers are valuable commodities when it comes to community outreach and research, as well as a boon to the economy.

Native Kansas flowers and the Kansas Prairie Photos by Jerry Jost of Kansas Land Trust and Craig C. Freeman

Nature is close at hand in Lawrence, with forest, grasslands, wetlands and wildlife practically within walking distance of the city limits. Understanding the role it all plays in both the environment and the economy is more of a reach, though.

That’s where the area’s network of advocates, educators and researchers comes in. Nonprofits and research centers like the Kansas Native Plant Society, Monarch Watch, Kansas Land Trust, Kansas Biological Survey and others play a vital role in fostering access and creating economic and intrinsic value within this community and beyond.

“Lawrence is a real nexus of activities related to knowledge and awareness of the environment, not just in Kansas but more broadly,” says Craig Freeman, who has long served on the board of the Kansas Native Plant Society (KNPS), which promotes awareness of the state’s native plants and their habitats through education, stewardship and scientific research.

Native Kansas flowers and the Kansas Prairie Photos by Jerry Jost of Kansas Land Trust and Craig C. Freeman

Environmental Economics

Those activities are more of an economic generator than they might appear. For one thing, such groups create employment, ranging from one contractual employee at the KNPS to 74 faculty, staff and graduate assistants at the Kansas Biological Survey (a University of Kansas research center often referred to as the Bio Survey).

Events and meetings also draw out-of-town visitors, who then spend money on hotels, restaurants and other amenities, Freeman notes. As many as 120 participants typically attend KNPS’s three-day annual meeting in a different Kansas town each year, while several thousand come to Lawrence for Monarch Watch’s various events.

There is “an economic benefit if you have to boil it down to dollars and cents,” says Freeman, who is a senior scientist at the Bio Survey and director of its R.L. McGregor Herbarium.

Still, organizations like KNPS “operate on a shoestring,” Freeman acknowledges, and so rely heavily on supporters. Dues from KPNS’s 800 members finance the budget, and it receives some grants for specific initiatives. Freeman’s wife, Jane Freeman, manages its administrative functions in Lawrence as the sole paid worker. Volunteers oversee the website and other activities.

Outreach includes holding Wildflower Walks and a photography contest, providing “Plant a Prairie” garden kits to teachers, offering a graduate student scholarship and creating educational events and resources. The cancellations of 2020 proved challenging for an organization that relies heavily on in-person interaction at field sites, but Freeman is optimistic about safely resuming some activities this year. One silver lining: KNPS has benefitted from learning to better utilize technology.

“We’ve increased the size of our toolkit,” Freeman says. Virtual forms of communication are “something we understand now, and we’re able to use it if we need to in the future.”

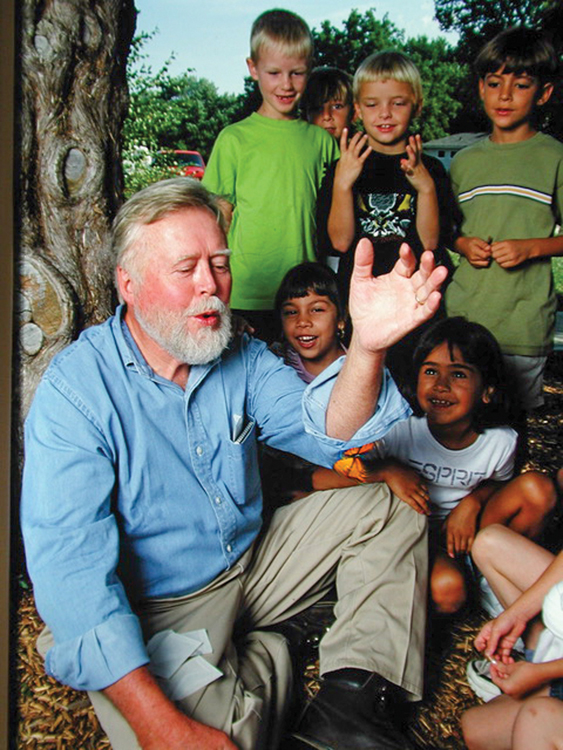

Orley R. “Chip” Taylor founder of Monarch Watch gives flyoung children an introduction to the world of butterflies

Butterfly Outreach

Monarch Watch also moved several of its marquee events online last year, but even a pandemic couldn’t shake this underlying truth: People have been enthusiastic about the outreach program since its beginning.

Orley R. “Chip” Taylor founded Monarch Watch in 1992 to facilitate monarch butterfly education, research and conservation, and still serves at its director. His first project was studying the monarch migration between the U.S. and Canada, and the species’ overwintering grounds in central Mexico; but he needed help collecting data. So Taylor invited the public to assist in tagging butterflies with tiny coded, all-weather circular tags and was gratified by the response.

“From the first year, I knew there was a thirst from the public to learn something about them,” he says. “They wanted to catch a butterfly, put a tag on it and learn more about this mysterious phenomenon.”

Thousands of volunteers across North American now tag some quarter-million butterflies each season, helping track their declining population. Expanding the monarchs’ habitat is essential to countering the slide, so in 2005, Taylor launched the Monarch Waystation program. It encourages people to plant milkweed and other host species, and now has 31,000 registered waystations in the U.S. and eight other countries.

“We’ve got a lot of sites around the country, but we need 10 times that many,” says Taylor, who is also a professor emeritus in ecology and evolutionary biology at KU. “If you want to sustain these things, you have to create habitat.”

Monarch Watch is affiliated with the Bio Survey, which provides it with facilities on campus. Between four and eight KU students work for it at any one time. The tagging and waystation programs are self-funded, merchandise sales generate other income, and Monarch Watch does have some grant support.

The program provides milkweed plants to schools, nonprofits and restoration projects; involves “citizen scientists” in research projects; and facilitates forums, communications and publicity. Monarch Watch’s spring open house and plant sale, fall open house and fall tagging event each normally attract between 600 and 800 participants to Lawrence, often from as far away as Minnesota, Mississippi and California, Taylor explains. Even more people visit throughout the year, and Monarch Watch frequently collaborates with researchers from other universities.

“We’re kind of an anchor for monarch studies and conservation,” Taylor says.

Orley R. “Chip” Taylor founder of Monarch Watch gives flyoung children an introduction to the world of butterflies

A United Cause

Environment-minded organizations also unite diverse groups within Lawrence. One example is Lawrence Ecology Teams United in Sustainability (LETUS), an interfaith network with representatives from First Presbyterian Church, Lawrence Jewish Community Congregation, Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Lawrence, Plymouth Congregational Church, Oread Friends Meeting, St. John the Evangelist Catholic Parish, Trinity Episcopal Church and the Islamic Center of Lawrence.

Together, they provide environmental advocacy and education on local issues, such as development of the 2040 Comprehensive Plan for Lawrence and Douglas County, as well as those with statewide impact, such as the Kansas Department of Agriculture’s efforts to update its Noxious Weed Guidelines.

Other nonprofits connect Kansans to a wider network of like-minded advocates. Take Friends of the Kaw. The grassroots group has for 30 years protected the Kansas River through environmental advocacy, educational paddle trips, speakers, a film festival and other programs. As the only Kansas member of the Waterkeeper Alliance, Friends of the Kaw is also helping fight for clean water on an international scale.

Similarly, the Jayhawk Audubon Society builds appreciation of birds and advocates for sustainability and preservation of intact ecosystems throughout Eastern Kansas. But even regional birding trips and events like the Kaw Valley Eagles Day help advance the National Audubon Society’s wider aims.

“We’re a part of the bigger picture,” says Jayhawk Audubon president Dr. James Bresnahan. “All these birds, like the warblers that come in the spring heading to Canada—we want to get the local population involved in appreciating that, but these are global issues.”

Protecting the Land

Environmental advocacy usually centers on management of public resources. But what happens when people want to protect their own private land? The Kansas Land Trust (KLT) was created in 1990 to help landowners do exactly that.

KLT collaborates with landowners to create voluntary, customized conservation agreements that protect areas with ecological, agricultural, historic, scenic or recreational value. Landowners can continue using their properties as they currently do, but they and all future owners are prevented from making man-made changes such as installing billboards or cell towers, building housing developments or fracking.

“It’s principally to keep the natural state of the land in perpetuity. If it’s farmland, it stays farmland. If it’s a wetland, it stays a wetland. If it’s prairie, it stays prairie,” says Jerry Jost, KLT’s executive director and its only full-time employee. The organization also has two part-time employees, and volunteers help with functions like monitoring compliance.

KLT has helped create 77 conservation easements throughout Kansas, including 11 in Douglas County. While most are private, some are open to the public, such as the Kelly-Varvil and Lichtwardt Conservation Easements. They’re part of the nearly 100-acre Lawrence Nature Park in northwest Lawrence and feature woodlands, a savannah, limestone outcroppings and walking trails. Ensuring access to that kind of green space enhances quality of life, improves residents’ health and makes Lawrence more appealing to businesses, Jost says.

Information about other accessible properties is on KLT’s website, and the nonprofit hosts guided hikes, Nature Detective Winter Outings for young children and other events. It all contributes to a more environmentally aware community while helping landowners meet their own goals, he explains.

“What we don’t know, we neglect. What we don’t appreciate, we neglect,” Jost says. “It’s important to get people outdoors and get them outdoors on protected lands.”

Native Kansas flowers and the Kansas Prairie Photos by Jerry Jost of Kansas Land Trust and Craig C. Freeman

Understanding Through Research

Understanding what’s out there is also essential. That’s the mission of the Bio Survey, which holds dual status as a nonregulatory state agency. Faculty, staff scientists, postdoctoral researchers and graduate and undergraduate students study terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems, and how those are impacted by humans. Projects range from analyzing harmful algal blooms and their effects across the state to grassland biodiversity, river ecosystems and remote sensing/GIS mapping applications.

The Bio Survey also manages the 3,700-acre KU Field Station, which was established in 1947 as a living laboratory. In addition to creating research opportunities, the field station also has a five-mile trail system showcasing woodlands and native prairie, and a Native Medicinal Plant Garden, both open year-round. It also offers occasional tours of the Baldwin Woods Forest Preserve, a research area that’s normally restricted and works with schoolteachers when possible.

The presence of such research expertise and the concentration of environmental nonprofits is a boon for Lawrence, because they all boost awareness, enthusiasm and engagement. Residents who understand such issues and appreciate the area’s unique resources are more likely to value and preserve them, making the city an even better place to live and work, the KLT’s Jost says.

“Every healthy community needs a broad menu of ways to be culturally, socially and intellectually engaged,” he says. “This is just one of those pieces on the menu.”

![]()