| story by | |

| photos by | Steven Hertzog |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

With the help of local residents and businesses, many associations exist to ensure Lawrence’s historic architectural treasures are preserved.

Renovation and restoration of stained glass windows by Hernly Associates

Piece by piece, the windows are coming back together. Part of the original St. Luke AME Church, built in 1910 at the corner of Ninth and New York streets, in downtown Lawrence, these majestic stained glass windows, with their mottled blues, greens and golds, were cracked, missing panes and in general disrepair. But just as the Lawrence community has come together to initiate a rehabilitation of this historic structure so that it can stand tall for another century of churchgoers, the windows themselves are being resurrected through the meticulous craftsmanship of Hoefer’s Custom Stained Glass, in Hutchinson, Kansas, and the funding efforts of the St. Luke AME congregation, the Douglas County Community Foundation, the Lawrence Preservation Alliance, the Douglas County Heritage Conservation Council and the Kansas Historical Society.

Lawrence has a long history of treasuring the architectural artifacts of times past. Founded in 1984, the Lawrence Preservation Alliance, the city’s nonprofit advocate for the preservation of historically significant buildings and natural environments, started when community members recognized their historic neighborhoods were vulnerable to demolition when solely economic concerns were taken into account.

Beginning as a grassroots effort to raise funds to purchase endangered residential properties that could be sold to individuals who recognized their historic value, the Lawrence Preservation Alliance quickly became a legal nonprofit entity and a leader in historic preservation initiatives within the city. It lobbied for the passing of a preservation ordinance, and as a result, Chapter 22 of the City Code was adopted by the City Commission in 1988. Chapter 22 established the Historic Resources Commission, a Certified Local Government endorsed by the National Park Service and the State Historic Preservation Office to maintain standards consistent with the National Historic Preservation Act within city limits. It also established the position of historic resources administrator, a salaried city staff position currently held by Lynne Braddock Zollner, as well as Lawrence’s local Register of Historic Places, an initiative designed to complement both the National Register of Historic Places and the Register of Historic Kansas Places.

Today, Lawrence is home to 12 historic districts, three urban conservation overlay districts and one national historic landmark: Haskell Indian Nations University. At the time of this writing, Lawrence has 65 properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places, 72 listed on the State Register of Historic Kansas Places and 94 listed on the Lawrence Register of Historic Places.

Not surprisingly, Lawrence is also home to a number of architectural and construction firms specializing in historic preservation and rehabilitation, including Form and Function, Gould Evans, Hernly Associates Inc., Natural Breeze, Rockhill and Associates, Struct/Restruct and Treanor Architects, as well as a number of craftspeople whose skills make detailed historic rehabilitations possible. While upholding our community’s commitment to historic preservation can be challenging and, at times, even controversial, through innovation, compromise and collaboration, we can ensure that the stories of our past survive within the walls and windows of our neighborhoods for years to come.

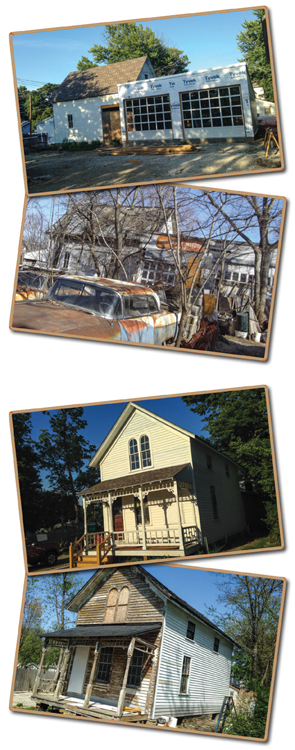

Renovation of 1106 Rhode Island by Hernly Associates

Why Preservation Is Important

Dennis Brown, president of the Lawrence Preservation Alliance since 2006 and a professional house painter who has been working on historic homes for more than 40 years, explains why he has chosen to commit so much of his life to the historic preservation of Lawrence’s neighborhoods: “When I walk up the steps inside the Douglas County courthouse, and I see the rounded impressions of thousands of feet that have gone up and down those steps for hundreds of years now, I think of all the many folks I wish I could meet, that I respect from our history, who were standing on these stairs just like I am right now. If you remove the building, you remove the tactile experience that connects you to that history.”

Brown’s dedication to preserving Lawrence’s historic architecture is practically unmatched, although he would be the first to try to pass any such accolades to someone else. His passion for history is evident, even as he deflects questions about his own contributions to the cause in order to focus on the original movers and shakers of Lawrence’s historic preservation movement, e.g. Oliver Finney, the first president of the Lawrence Preservation Alliance; Marci Francisco, Kansas state legislator who was one of the original galvanizers of the Alliance; and Dennis Domer, prolific historian of Lawrence’s many neighborhoods and retired professor of American Studies at the University of Kansas.

The history of our neighborhoods and preservation of the architectural landscape seem especially important at this cultural moment during which so many of us are confined to our homes, cut off from our larger communities and compelled to transition our social interactions from the brick-and-mortar backdrops of offices and meeting halls, bars and coffee shops, to the digital realm. As our everyday interactions with the environment outside our individual domiciles are diminished, it is, perhaps, exactly the time we must listen most carefully to what historic resources commissioner and architectural historian Brenna Buchanan calls “the voice of the structure.” “I see myself as being a steward of the architecture,” she confides. “It can’t speak for itself, so I try to be the voice for the structure, the voice for the home.”

Top: Landon Harness founder of local construction and design company Form and Function in front of a finished project on Connecticut Street and working on a new project; Bottom: The staff of Hernly Associates Inc and Hernly Environmental Inc; Joni and Stan Hernly

Finding Compromise

For both Brown and Buchanan, the act of historic preservation is one of humanizing the architectural landscape and bringing the stories of Lawrencians past back to tangible life. But historic preservation has its detractors—often those who see it as costly, difficult, bound up in bureaucratic red tape or all three.

If you ask Landon Harness, co-founder of local construction and design firm Form and Function, they’re not totally wrong. “It’s a labor of love,” Harness says. “Historic homes can be more difficult to work on than new construction. You have to find the right windows, find the right trim, find the right tile.” And of course, extra work on behalf of the contractor means extra costs on behalf of the property owner.

Fortunately, federal and state government have recognized the extra challenges historic preservation work can present and the additional costs it can incur. To offset these costs, the U.S. Department of the Interior developed a tax-credit program that provides a 20% income tax credit to taxpayers rehabilitating income-generating historic structures listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the state of Kansas offers a 25% income tax credit to taxpayers rehabilitating residential or income-generating structures listed on the National Register of Historic Places or the Register of Historic Kansas Places in accordance with federal historic rehabilitation standards and guidelines. This state tax credit goes up to 30% if the taxpayer is a certified 501(c)3 nonprofit, and the national and state tax credits can be combined.

Dennis Brown, president of the Lawrence Preservation Alliance

Stan Hernly, principal architect and founder of Hernly Associates Inc., the national and/or state tax credits are usually more than enough to offset the additional costs accrued as a result of a historic rehabilitation project in compliance with federal preservation guidelines. In addition, Hernly points out, “You’re preserving the main structure, and there are a lot of costs and a lot of energy expended in the original construction of any building. If we tear that original structure down, all of those costs and all of that energy is just thrown into the landfill. Rehabilitation is really one of the best ways to approach resource conservation both in terms of finances and in terms of energy, because you’re keeping what was put into the construction of that building in the first place.”

Joni Hernly, owner of Hernly Environmental Inc. and Stan’s life as well as business partner, agrees. Running a business committed to conducting safe and healthy environmental testing for toxins often found in historic structures, including lead-based paint, mold, asbestos and radon, while also working as a rehabilitation tax-credit specialist at Hernly Associates, she explains historic rehabilitation is an environmentally friendly practice that doesn’t have to be intimidating, although each project is different. “The first step for any historic rehabilitation project is to have a knowledgeable consultant or contractor do a walkthrough,” she says. This helps clients understand the best way to achieve their goals while maintaining key elements of the structure and adhering to the necessary standards and guidelines.

In addition to offsetting the costs of historic rehabilitation to the property owner, historic tax-credit programs also benefit the communities in which they operate. According to the National Park Service, the Federal Historic Tax Credit program created 2.54 million jobs, generated $89.97 billion in rehabilitation investment and established 160,058 low- and moderate-income housing units in fiscal year 2017 alone. At the state level, the Kansas Preservation Alliance reports the Kansas Historic Tax Credits program generated 4,443 jobs and $141.6 million in income for Kansas residents between 2002 and 2009.

While there are currently no city tax credits for historic preservation projects, such projects produce socioeconomic benefits at the local level, as well. In addition to generating jobs and income for Lawrence residents who work in the historic rehabilitation field, historic preservation projects and historic districts also attract visitors. As the City’s Zollner explains: “Aside from being environmentally sustainable, historic preservation can be a real boost to city tourism. Many people travel to learn about local architecture and to feel the history of a place, and that brings in business to our larger economy. Having these historic listings and sites available for people who want to visit is a benefit to the entire Lawrence community.”

Top: Landon Harness founder of local construction and design company Form and Function in front of a finished project on Connecticut Street and working on a new project; Bottom: The staff of Hernly Associates Inc and Hernly Environmental Inc; Joni and Stan Hernly

Standing Stronger

The Rev. Verdell Taylor Jr., leader of East Lawrence’s St. Luke AME congregation for more than 26 years and was responsible for getting the church listed on the national historic registry shortly after his arrival in Lawrence, has also been a member of the Lawrence Preservation Alliance board for more than 20 years. He confides: “The intricacies of older buildings, the detailed work on older homes, always attracted me. When I learned that St. Luke AME had been the childhood church of Langston Hughes, I knew we had to get it on the registry.”

Photographs of the church’s stained glass windows being restored pane by pane have been getting an impressive number of likes on the Lawrence Preservation Alliance’s social media accounts. What is it about the windows? “They just give you a special feeling,” Taylor says. “There’s a reverence, something spiritual about them that we can’t quite understand. When you drive by them, and they’re all lit up inside, or you sit quietly within the church feeling the sunlight come in around you, it’s a kind of sanctuary that’s been passed down through the generations.

“You know, I’m a pastor and a God-believing man, and the only thing that kept those windows in the church walls was God himself; because without God’s help, those windows would have fallen out of there,” he chuckles.

It’s easy to laugh now knowing the windows are on the mend. And thanks to support from the Lawrence community, they’re going stand up stronger than ever, gracing the corner of Ninth and New York streets with a century of stories for at least another hundred years.

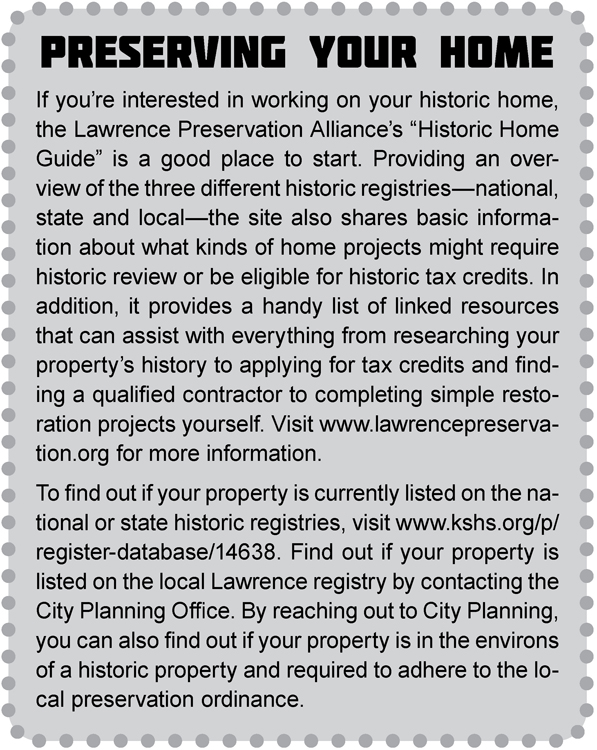

Preserving Your Home

Preserving Your Home

See if Your House Deserves a PIP Award

PIP Award

![]()