| story by |

Looking back at the last pandemic in the United States, the Spanish flu, reveals just how devastating an uncontrolled virus spreading through a community can be.

Does History Repeat Itself

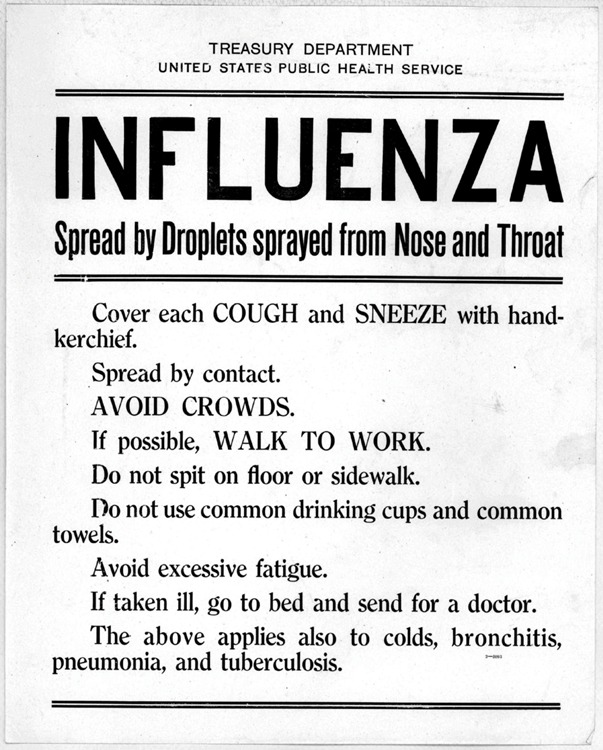

Wash your hands. Stay at home. Close the schools. Statewide shutdown order issued. Do these admonitions sound familiar? They were part of the effort to combat the Spanish flu in 1918, but these safety efforts heard today are to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

The Spanish flu epidemic, which had no established connection with Spain, was also known as the 1918 flu pandemic. It was a deadly strain of the H1N1 influenza A virus. There were four waves, but the second wave was the deadliest. It reached its peak in Kansas in October 1918, with more than 292,000 deaths nationally between September and December 1918. The pandemic may have started in Kansas, when one of the first cases reported was at Camp Funston, Fort Riley, Kansas. The U.S. was still fighting World War I, and Camp Funston trained thousands of new soldiers who traveled through Kansas.

Obviously, Lawrence was impacted by the pandemic. On Oct. 8, 1918, schools and theaters were closed. The story on Page 1 of the Lawrence Daily Journal-World for October announced:

University And Schools Ordered Closed Today by State Health Authorities

- Theaters, Churches, And Clubs of Lawrence Follow Suit And Go Into Voluntary Quarantine Against The Spread Of The Spanish Influenza Which Now Threatens The Population And The Student Body

- Ninety-Two Cases Reported On “The Hill”

W. W. Holyfield, acting mayor of Lawrence, issued a proclamation that also appeared on the front page of the Oct. 8 newspaper. It stated, in part:

- Now, Therefore, I hereby order and direct that all public and private schools, church services, lodge meetings, theaters, picture shows, and all public assemblages of people be suspended until further notice and that there be no gatherings of more than 20 people in one place.

One of the complicating factors was that approximately 3,000 young men were undergoing military training as part of the Student Army Training Corps (SATC). Barracks were built near campus and, because of living in close quarters, the trainees were the victims of most of the cases of the flu in Douglas County.

On Oct. 12, Kansas Gov. Arthur Capper issued a statewide closing order for one week to try to stop the spread of the virus; and on Oct. 18, the order was extended for one week. The closings were announced following a long-distance telephone discussion with Dr. S. J. Crumbine, director of the State Department of Health, Governor Capper and Chancellor Frank Strong. Students were warned that travel by train (which was the primary form of transportation for college students) “is one of the most sure ways of spreading and becoming infected with the influenza, and the students are advised to remain in Lawrence until school is reopened.” Crumbine acknowledged that if “crowds again are permitted to congregate, one bad case in a school, church or theater would be sufficient to affect every person susceptible.” Sound familiar?

Public schools in Lawrence and Douglas County were also impacted. County Superintendent of Public Schools O. J. Lane and the City Superintendent of Public Schools Raymond A. Kent ordered local schools to be closed to implement the statewide closure order. Finally, on Nov. 11, the ban was lifted, but local governments were encouraged to develop their own restrictions and precautions.

The 1918 pandemic included the closure of billiard and pool halls “except for the sale of cigars and similar articles. The following conditions were required if drinks were served: All glasses, spoons and other utensils served to the public shall be thoroughly sterilized by boiling water or live steam; of that in lieu thereof paper cups and dishes should be used. Health officials, police officials and sheriffs are called upon to see that this order is obeyed.” A. W. Clark, the Lawrence City Health Officer, also addressed concerns about barber shops. He believed that “the dangers of barbers conveying to or taking from their clients the influenza infection is probably greater than any other profession. Until further orders, all barbers while actually at work are required to wear gauze masks closely covering mouth and nostrils. At least four thicknesses of gauze about 5 inches square should be used with a tape at each of the four corners to tie at the back of the head and back of the neck. Shops not complying with this order will be closed.” Sound familiar?

Other impacts of the pandemic were described by the newspaper. Patrons of the public library were assured that all books returned to the library would be fumigated before they were put back in circulation. It was noted that train traffic was down, with only two people leaving Lawrence on the morning trains. Mail delivery was slowed because two of the mail carriers had contracted influenza. Local florists had difficulty filling the “abnormal demand for flowers resulting from the influenza epidemic because greenhouses had to abide by U.S. fuel administrations restrictions because of World War I.” When a local druggist had trouble receiving orders of antiseptics, atomisers and other articles needed to fight the flu, he found a creative way to combat his shortages. The druggist was Walter Varnum, of the Round Corner Drug Store. He “turned his pleasure automobile into an automobile express car and with it has been relieving the emergency created by the influenza epidemic.” He made two trips to Kansas City and brought back a large number of supplies needed by the medical community.

In early November, Crumbine reported that there were about 50 cases in Lawrence hospitals, and another 200 convalescents would be unable to attend classes. Crumbine also stated “that conditions in many localities were not as favorable as they are here, and if some thousand or more students were brought back here from all parts of the state, the condition of about a week ago would be repeated.” In 1918, Lawrence did not have a public hospital. Several doctors provided beds for patients in their clinics/home, and the Social Service League Hospital operated a charity health clinic located at 546 Vermont St. These facilities were filled with influenza patients. The Lawrence Daily Journal-World reported on a Black man who had become seriously ill on an Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe train. Paul W. Conners, of Prescott, Arizona, was removed from the train. The Social Service League Hospital was full, so he was kept at the police station overnight. The next day, “local colored Masons” arranged for him to be cared for in a private home.

At the urging of Mayor George L. Kreeck, the Lawrence Red Cross quickly set up an emergency ward at 826 Mississippi St., courtesy of the Bullene estate. Furniture, beds and other linens were donated by private families. Dr. A. W. Clarke, the city health officer, was appointed superintendent of the hospital, and Mrs. Ruth Seaman was named head nurse. A call was made for additional nurses, but most of them were already involved in treating influenza cases. Other women were encouraged to volunteer, even if they did not have medical training. In some homes, everyone in the family was ill, and neighbors were urged to check on each other and help, as needed.

As indicated earlier, many of the young men undergoing training as part of the SATC had the flu. The Lawrence Chapter of the Red Cross answered the call for assistance. It helped recruit 10 graduate nurses, 12 practical nurses and 55 nurses’ aides. The Red Cross also reported it had provided the following supplies: 496 suits of pajamas, some 1,800 gauze masks, 155 bed slippers, 260 sleeping helmets, all manufactured in their work rooms. The chapter also furnished 340 bed sheets, 347 pillowcases, 294 pillows, 420 towels and 155 washcloths, all gathered from house-to-house campaigns.

While the influenza pandemic reached its height in October 1918, additional cases were reported into 1919. It is difficult to locate statistics about the number of cases in the state of Kansas and its communities. In Kansas, 12,000 had died from influenza by 1919. However, impact of the Spanish flu was immense. It is estimated that the disease killed between 16 and 30 million people worldwide, and was responsible for 675,000 deaths in the United States alone. The Spanish influenza was responsible for twice the number of casualties (both killed and wounded) of the United States in World War I, which totaled near 323,000.

To end on a slightly lighter note:

- There was a little bird,

its name was ENZA

I opened the window

And in-flu-enza.