| story by | |

| photos by | Steven Hertzog |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

The potential to expand and enhance Downtown Lawrence is there, but the ideas and decision-makers must come together to make it happen.

Steve Nowak-executive director for the Watkins Museum of History; Jane Huesemann-Principal architect at Clark/Huesemann

Talk to anyone who has ever lived in Lawrence, and they remember the particular Mass. Street location of their favorite store/restaurant/bar/attraction. Downtown Lawrence means different things to just about everyone, but it is pretty much always the touchpoint for life in Lawrence.

We can so easily talk about the downtown of the past, longing for that meaningful place or experience. But what about the future? Where, metaphorically, is downtown headed? What could or should it become? The answers to that are as varied as the storefronts downtown, and the only limits are imagination (well, and possibly money and consensus, and some other small details).

Steve Nowak, Jane Huesemann, Brandon Graham and Kirsten Flory are but a few of the people for whom downtown has been a workplace and/or residence. Their vocations and experiences position them to be able to speak to what they see as the future of Downtown Lawrence.

Nowak has been executive director of the Watkins Museum of History for 13 years. Huesemann has been a principal of Clark Huesemann, architecture and design firm, for 12 years and came to Lawrence in 1988. Graham has owned Jefferson’s restaurant for 13 years and grew up in Lawrence. Flory has worked in commercial real estate in Lawrence for 11 years and started her firm, Foundations Commercial Real Estate, in 2021.

Collectively, they see the potential for expanding event spaces downtown, increasing pedestrian areas and pathways, connecting downtown with The KU Gateway District and widening conversations and regulations to promote more community collaborations.

Brandon Graham-President/Jefferson’s Franchise SystemsBrandon; Kirsten Flory-President & CEO Foundations Commercial

Long-Term Future

The variety of ideas about Downtown Lawrence and the range of people who have them can be both a blessing and a curse, it appears. The community as a whole values downtown, but streamlining the voices and ideas into tangible action seems to cause overall momentum to fizzle.

LOCAL MATTERS

Our Local Advertisers – Making a Positive Impact

“Our biggest challenge about downtown is getting people to talk face-to-face. We all love that area. We want to keep its attributes; we just have to do it together,” Flory explains.

There is no shortage of data or information about downtown’s characteristics, Huesemann says. It’s collecting that data and harnessing it intentionally for planning purposes that presents challenges.

“A more cohesive effort would give the city a framework to approve projects. It ought to be more a design effort than just a bunch of regulations, and those projects would get backing on them. There are lists of needs already established by many groups for so many years. If we collaborate, we can put all the data into a compelling report that links together the needs, leading to the potential for grants and other resources for amenities and improvements downtown,” Huesemann says.

From city rules and regulations to relationships with the two universities in town, all would like to see open communication and novel collaborations come into being.

The old front of Jefferson’s at 743 Mass St; Renovation begins; Rendering of Jefferson’s by Paul Werner Architects; The original building at 743 Mass St-inside the red box

Rework What’s Already There

So what should change downtown in the medium- to long-term?

Though its streets, sidewalks and parking lots have long doubled as event spaces for parades, celebrations, concerts and fundraisers, establishing a dedicated space and infrastructure for gatherings would serve the area well, all four agree.

Nowak envisions changing a space such as the parking lot at Eighth and Vermont streets, plus closing off the block of Eighth Street between Massachusetts and Vermont streets to create an open pedestrian and event area. The library parking garage on Vermont Street faces that space, and “you’ll feel like you’re already downtown when you park in that garage,” Nowak says. Other spaces farther south near South Park could fulfill the same function.

“Downtown is at its best when you walk. You need to leave the car and experience it on foot so you can see the store windows and encounter people on the street,” he continues. By creating an open space near existing parking, Nowak says people will perceive it as being simpler to park and walk around. Flory says that having traffic-free spaces brings about a collaborative, community feel to the surrounding areas.

Huesemann also likes the idea of creating an event space and even suggests combining it with a permanent covered pavilion and public restrooms. The farmers market could take place in the pavilion on designated days, and the rest of the time, the space could be reserved by community groups—and even the University of Kansas (KU)—for events.

The City of Lawrence has established RFPs (requests for proposal) for the surface parking lots on New Hampshire and Vermont streets, and Flory says she hopes the city will be open to the creative possibilities of some of the proposals. Often, the city is too hung up on historical standards that don’t make sense, and that sometimes hinders development, she adds.

Huesemann agrees. “We make it so hard for developers to make a successful project that we end up with empty lots,” she says.

Outside the Cider Gallery in the Warehouse Arts District

Connect Downtown and KU

The KU Gateway District, being constructed around KU’s Memorial Stadium, presents opportunity for a westward connection emanating from downtown to the University and points beyond. Graham says downtown ideally should continue to be home to a majority of locally owned small businesses, with a constant evolution of merchandise shops, restaurants and activity-based storefronts. KU students and workers, as well as tourists, are the core of downtown business’ success, so luring them from The Gateway District east on Ninth Street is critically important.

“Downtown appeals to and attracts a giant melting pot of people. That’s the nature of the diversity of experiences down here,” Graham says.

Nowak suggests creating a west-facing entrance to clearly show visitors how close they are to downtown when they are in the area directly west of Mass. Street. Having clearer signage about parking and access points will also help out-of-towners better navigate the area, Huesemann continues. Further, enticing people downtown likely will also lead them to the Warehouse Arts District and other points of interest to the north and east of downtown, Flory says.

Huesemann notes that establishing downtown’s presence on its west side also could help the city cultivate its relationship with the University in new and unique ways, while bolstering neighborhoods and businesses in between.

Many Lawrencians worry that Downtown Lawrence will evolve into solely a bar district, where stores and shops might get squeezed out by increasing rents. Storefronts that offer activities and experiences, such as breakout rooms and ax-throwing venues, build a bridge that keeps the area active at all times of the day and appeals both to locals and visitors of all ages, Graham emphasizes. Downtown also serves as the center of the city’s intellectual life, Nowak says, with the Lawrence Public Library, Lawrence Arts Center and Watkins Museum.

“Ideally, downtown is one thing at night and another thing in the day. It should be a place to explore new ideas, celebrate and meet your friends, and it should keep growing in those roles but be more diverse in them,” Nowak says.

Outdoor dining at the Mass Street Fish House & 715

Creative Change

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the city’s hand on formalizing new types of outdoor spaces with the creation of parklets—those areas in front of downtown restaurants and bars that each took over a couple of Mass. Street parking spots. All four are in favor of keeping the parklets, and they all mentioned taking that idea further, either with more elaborate design elements as Huesemann suggests or by doing a trial shutdown of a block or two of Mass. Street, as Graham proposes and Flory supports.

Graham points out that the parklets were initially temporary, and the community responded positively, both when they were in a trial period and when they were approved permanently. That process established a new possibility for exploring ideas downtown, he continues, by doing shorter-term trials and then gauging response and viability.

Proposed developments for long-empty properties at Sixth and New Hampshire streets are an “exciting” prospect for what has been a quieter portion of downtown, Flory says. She hopes those projects will lead to rethinking the entire riverfront, including the Riverfront Plaza and even the area along the river by Johnny’s Tavern, in North Lawrence.

“The lower floors of the Riverfront Outlet Mall are kind of a hidden gem, because that space overlooks the river,” she says.

Huesemann agrees and would like to see the riverfront develop even farther east, beyond the mall building. The river should be a focus of recreation, allowing access to the water for boating and other activities, she suggests. Near the Amtrak station at Seventh and New Jersey streets, the river is at road level without the steep banks elsewhere.

“Enhance the edge of the river so that there are places you can get to. I picture stores and a coffee shop right there by the bike path near the train station. Right now, you don’t know the river is there unless you purposely seek it out,” Huesemann says.

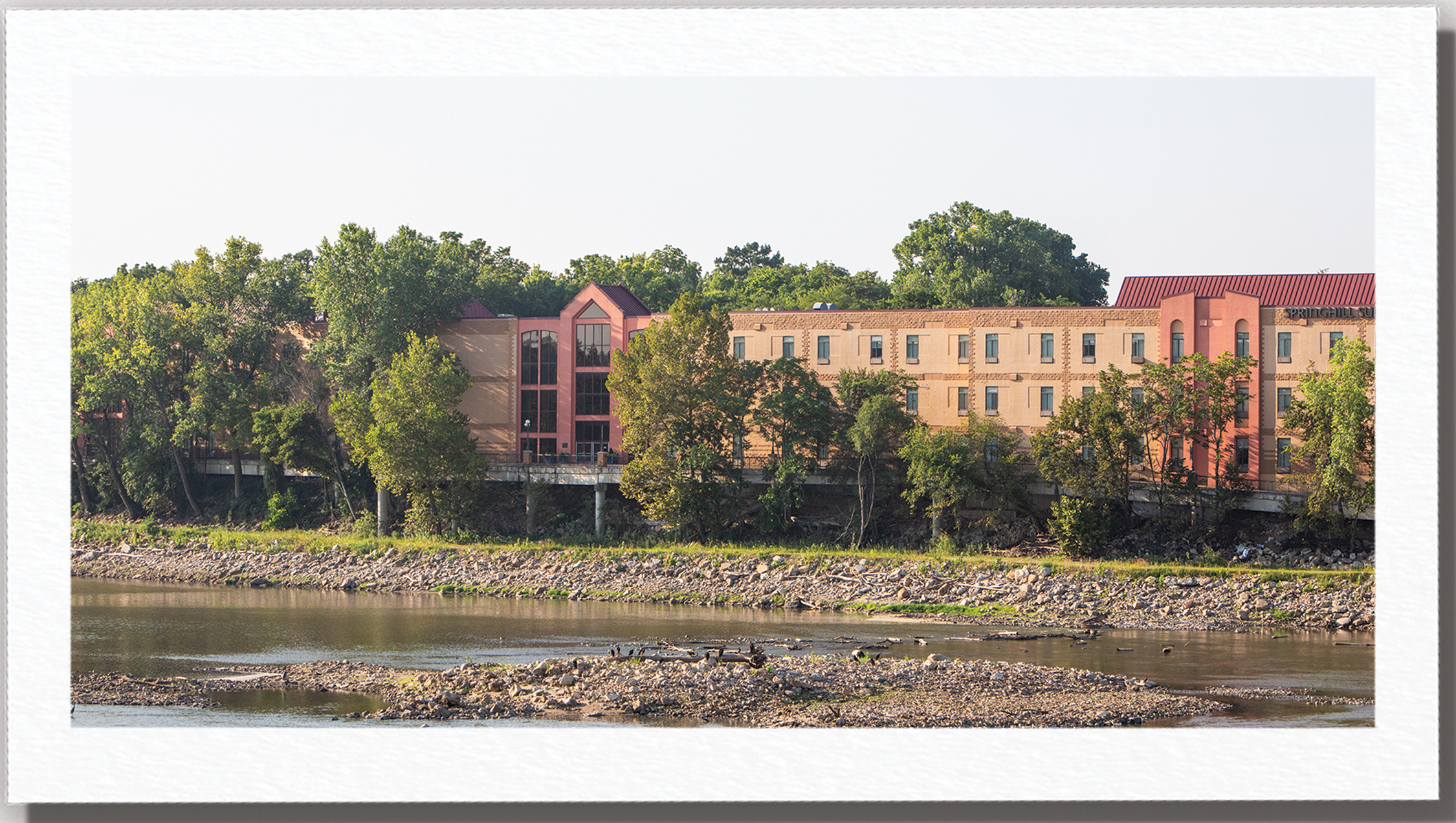

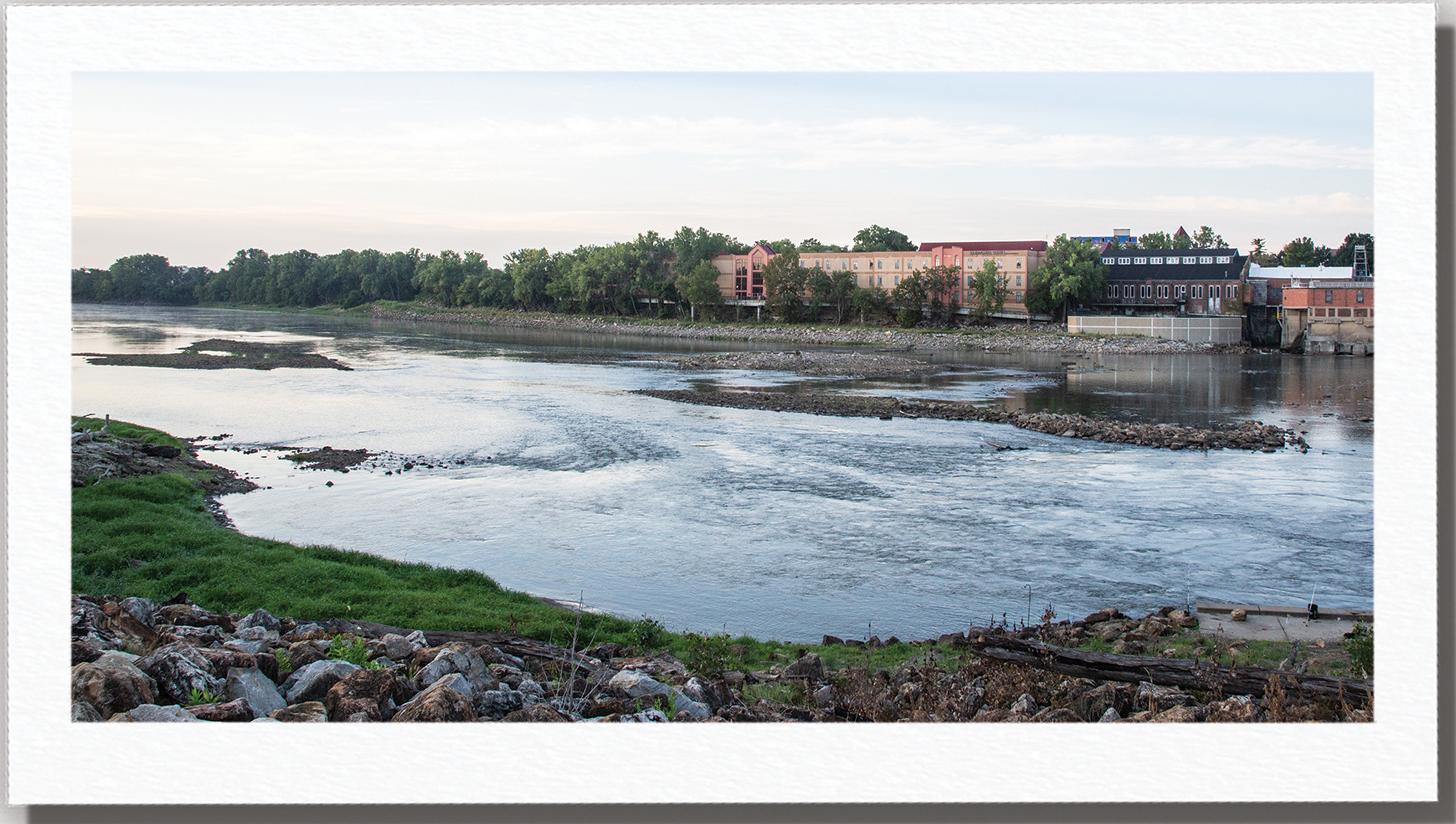

The warehouses of old Lawrence on the Kaw River; The southside of the Kaw River, known as the Riverside Mall, has much potential for growth; Closeup: the southside of the Kaw River, known as the Riverside Mall, has much potential for growth

The warehouses of old Lawrence on the Kaw River; The southside of the Kaw River, known as the Riverside Mall, has much potential for growth; Closeup: the southside of the Kaw River, known as the Riverside Mall, has much potential for growth

Make Old Space New

While looking to cast the proverbial net wider for downtown, equally important is to scrutinize the existing spaces and storefronts in the 150-year-old buildings in and around downtown, Flory says. Clark Huesemann chose to locate their offices downtown, but they are architects, so they had the ability to customize their space in the 900 block of Mass. Street.

So many companies would like to have their offices and headquarters in Downtown Lawrence, Flory says, but they are unable to do so because of the types of spaces in downtown buildings. A typical storefront is 25 feet wide by 100 feet deep, which is 2,500 square feet. Most businesses want about 1,500 square feet of space, Flory says, so downtown spaces aren’t functional for them.

“The challenge is: How do you divide the space? The price per square foot is lower in downtown, but you combine it with the bigger footprint, and it’s more expensive,” Flory says. There are many 1,500-square-foot spaces available in western Lawrence, but then the businesses and employees miss out on all that downtown has to offer. Flory says businesses often choose instead to locate in Kansas City, where there is more to do and younger people, than in western Lawrence.

Attracting more residents to downtown and continuing to develop more residences in and near downtown is critical to its future success, as well.

“More housing and more density, and trying to motivate and encourage that kind of development is healthy for the business district,” Graham says. “I would love to have 2,000 more potential customers within walking distance.”

More people living downtown would create change downtown, making daily life there more convenient and allowing more people to experience it without having to drive, Nowak says. Without a grocery store and some other conveniences, he says downtown isn’t as easy of a place to live as it could be.

When downtown exists as both a business center and a home for people, that ensures its long-term relevance and viability.

Downtown has had three purposes since it was designed and built in the 1850s, Nowak says: a mercantile center, a place for people to relax and socialize, and a community celebration location.

“Past, present and future live together very well,” he says. “How we use downtown may change over time, but the fact that it’s central to our identity will never change.”