| story by | |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

This self-taught Midwest boy discovered Pluto early in life and lived out his dreams of earning college degrees and contributing to the field of astronomy through his significant discoveries.

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft captured this high-resolution enhanced color view of Pluto on July 14, 2015.

How does a boy who grew up on the plains of north-central Illinois and the prairies of southwest Kansas become a world-renowned astronomer? Clyde W. Tombaugh, who discovered the planet Pluto, described how it began in a 1986 oral history interview with George M. House, curator of the International Space Hall of Fame, at New Mexico State University (NMSU), in Las Cruces, New Mexico. In response to a question about how he got interested in astronomy, Tombaugh said it was because he enjoyed geography.

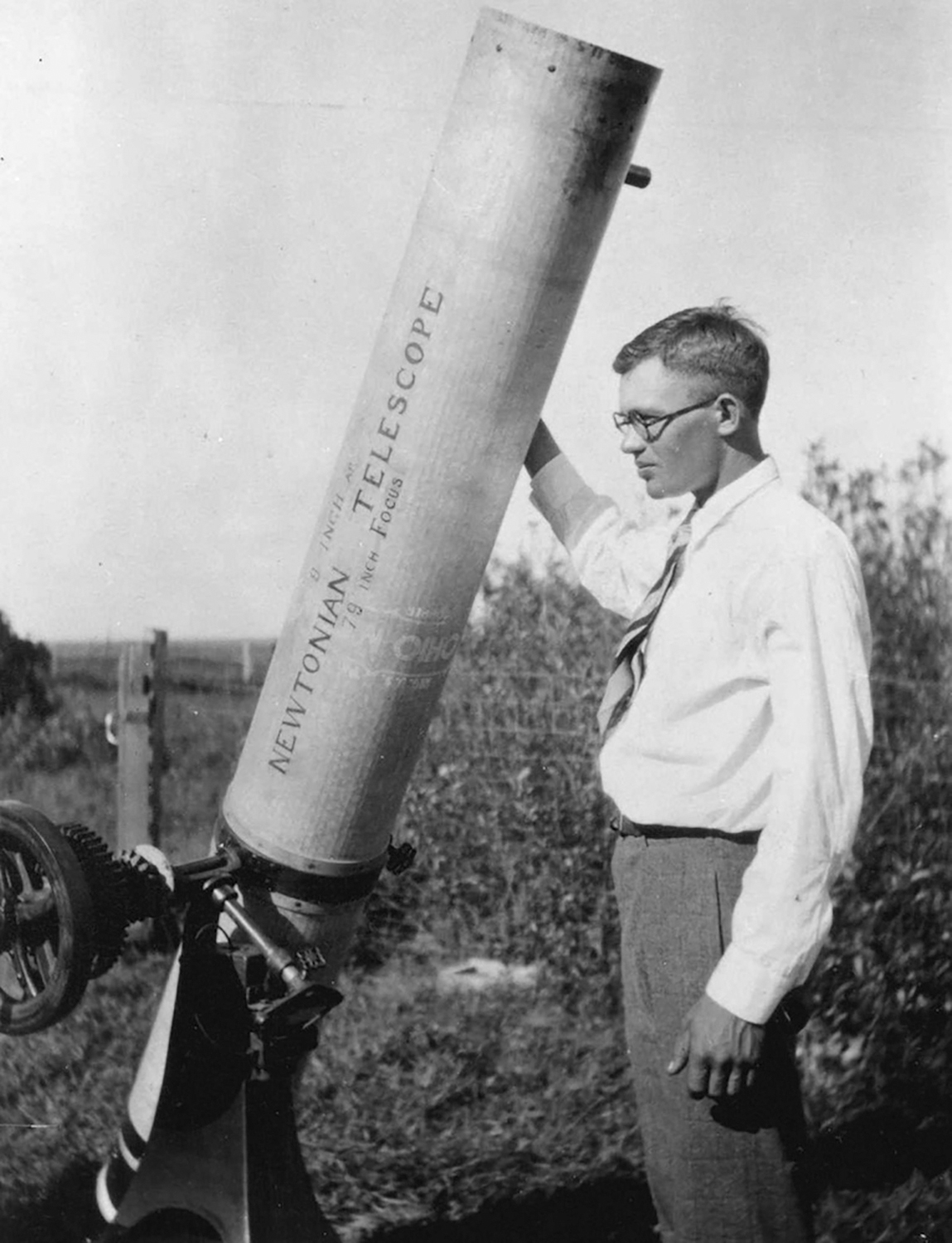

When he was in fifth or sixth grade, Tombaugh began to think about the geography of other planets. He started observing the night sky when his Uncle Lee, who lived near the Tombaugh family farm, in Streator, Illinois, gave him a 3-inch telescope. With it, Tombaugh saw Saturn’s rings and Jupiter’s moons and craters. In 1920, his father and uncle purchased a 60 millimeter telescope from Sears, Roebuck and Co. However, he wanted a telescope with more power. The family didn’t have money for things that weren’t necessities, so Tombaugh began building his own.

When asked when he built his first telescope in an interview published in the “Academy of Achievement” journal, Tombaugh responded:

- That was in 1926. I was 20. It wasn’t a very good one because I had such meager instruction. It worked fairly well, but not good enough to suit me. The following year, Scientific American published a book called “Amateur Telescope Making.” I bought a copy and digested it and realized where I’d made mistakes. … The nine-inch in my backyard, for instance, was my third telescope of excellent quality. It was the drawings I made of the markings on Mars and Jupiter with that telescope that I sent to the Lowell Observatory in 1928. That impressed them favorably so that they invited me to come out for a trial work with the new telescope at Flagstaff. That was a big break.

The observatory was installing a new photographic telescope and thought Tombaugh would be a viable candidate to operate it. He went to Flagstaff for a three-month trial and stayed 14 years. At the time, he only had a high school degree but had studied math and astronomy on his own.

Astronomers believed there might be another plant in the universe they called Planet X. Tombaugh was given the task of trying to document it with the new telescope. He took photos with the telescope and then studied them on a special machine called a blink comparator. He would compare two plates rapidly in alternating views to see if a change occurred in the star field.

LOCAL MATTERS

Our Local Advertisers – Making a Positive Impact

“That was the technique, because these plates would have several hundred thousand star images a piece,” Tombaugh said. “That’s an awesome thing to look at and realize you had to see out of all those images which one moved.” This was because the stars were in fixed positions, but the ones that moved were planets orbiting the sun.

Tombaugh described how he finally determined there was a new planet on the photographic images he took in January 1930.

- I did not know that I had recorded the image of Pluto on those plates, not until I scanned them later in February. You passed your gaze over all of these stars that you have to be conscious of seeing every star image, because you don’t know which one’s going to shift, if they shift. It’s very tedious work and you go through tens of thousands of star images. I came to one place where it actually was, turned the next field and there it was! Instantly I knew I had a planet beyond the orbit of Neptune because I knew the amount of shift was what fitted the situation. That was the instantaneous thrill you can imagine. It just electrified me!

It was Feb. 18, 1930. Tombaugh realized he had made a great discovery, and his life would change from that point on.

Clyde Tombaugh. (2024, May 20). In Wikipedia.

Carl Lampland, assistant director of the Lowell Observatory and colleague, had an office across the hall from Tombaugh. He had been hearing the click of the blink comparator as Tombaugh worked on the photographic plates. Suddenly there was silence, and Lampland surmised Tombaugh had discovered something significant. He waited to be invited into the office to see what Tombaugh found. They then showed Earl Slipher, director of the observatory, the plates and data associated with them. The staff decided to name the planet Pluto for the god of the underworld. It seemed to fit because the planet was so far away from Earth out in the darkness.

Tombaugh and the Lowell Observatory received lots of publicity, and he tried to answer the thousands of letters received from all over the world. During the years Tombaugh worked at the observatory, he discovered hundreds of new variable stars and asteroids, and two comets. He also located new star clusters and clusters of galaxies, including one supercluster of galaxies.

Tombaugh had always wanted to go to college and was offered a scholarship to the University of Kansas (KU), in Lawrence, Kansas. He attended KU from 1932 through 1936, receiving his bachelor’s degree, and returned to the Lowell Observatory to work during the summers.

Tombaugh had shared astronomy classes with fellow student James Edson, who encouraged him to rent a room at his mother’s home. In the fall of 1933, Tombaugh moved to Lawrence to begin classes. He enrolled in a beginning astronomy class, but the professor of the class felt it was inappropriate for the discoverer of Pluto to be in that class. Tombaugh, Edson and four or five other students formed a club they called Syzygy, which meant the conjunction of the moon with the sun.

He met his wife, Patsy, Edson’s sister, in the spring of 1933 while living at Edson’s mother’s home. Patsy joined Syzygy as they talked about rockets, space travel and astronauts. She even painted tennis balls to look like Mars and Jupiter, which impressed Tombaugh. The couple married on June 7, 1934. Tombaugh went back to KU in 1938 and 1939, and earned his master’s degree in astronomy.

During World War II, Tombaugh taught navigation to new Navy pilots at Northern Arizona University. In 1945, he was a visiting professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. He was then named chief of the Optical Measurements section at White Sands Proving Ground, at Las Cruses, New Mexico, in 1946, where he worked with rockets for nine years. But he decided he wanted to get back into astronomy. Tombaugh returned to NMSU in 1955 and taught there until he retired in 1973. He helped create a department of astronomy doctoral program there.

Tombaugh was involved in community activities and was in demand as a speaker. He received so much mail that at one point he told colleagues he received 20 e-mail letters a day and 6 inches of mail in his university mailbox. Tombaugh was known for making puns, but when he declared, “I get so much mail that it is downright astronomical,” his colleagues laughed because he didn’t realize he had made a pun. One of his favorite puns was, “What do you call an angry crow?” The answer was a “raven maniac.” When a security guard at a White Sands entry gate told him his wheels weren’t moving, Tombaugh told him that “they are tired.” An unnamed friend made his own pun about Tombaugh saying he “was the only true plutocrat.”

Clyde Tombaugh was a brilliant man. In his early years, he taught himself about mathematics, science and astronomy. He persevered until he found the kinds of jobs he found rewarding. He was always constantly learning new things and following new developments in his field. Fittingly, some of his ashes were interred in the New Horizons spacecraft, the first to explore Pluto up close, flying by the dwarf planet and its moons in 2015. It is one of five spacecraft that would eventually leave our solar system traveling at 300,000 miles per year. This spacecraft continues Tombaugh’s lifelong dream of learning more about the solar system and beyond.