| story by | |

| photos by | Steven Hertzog |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

An invaluable local agency, Douglas County Emergency Management educates the community, plans for varied situations and assembles support systems for possible large-scale emergencies.

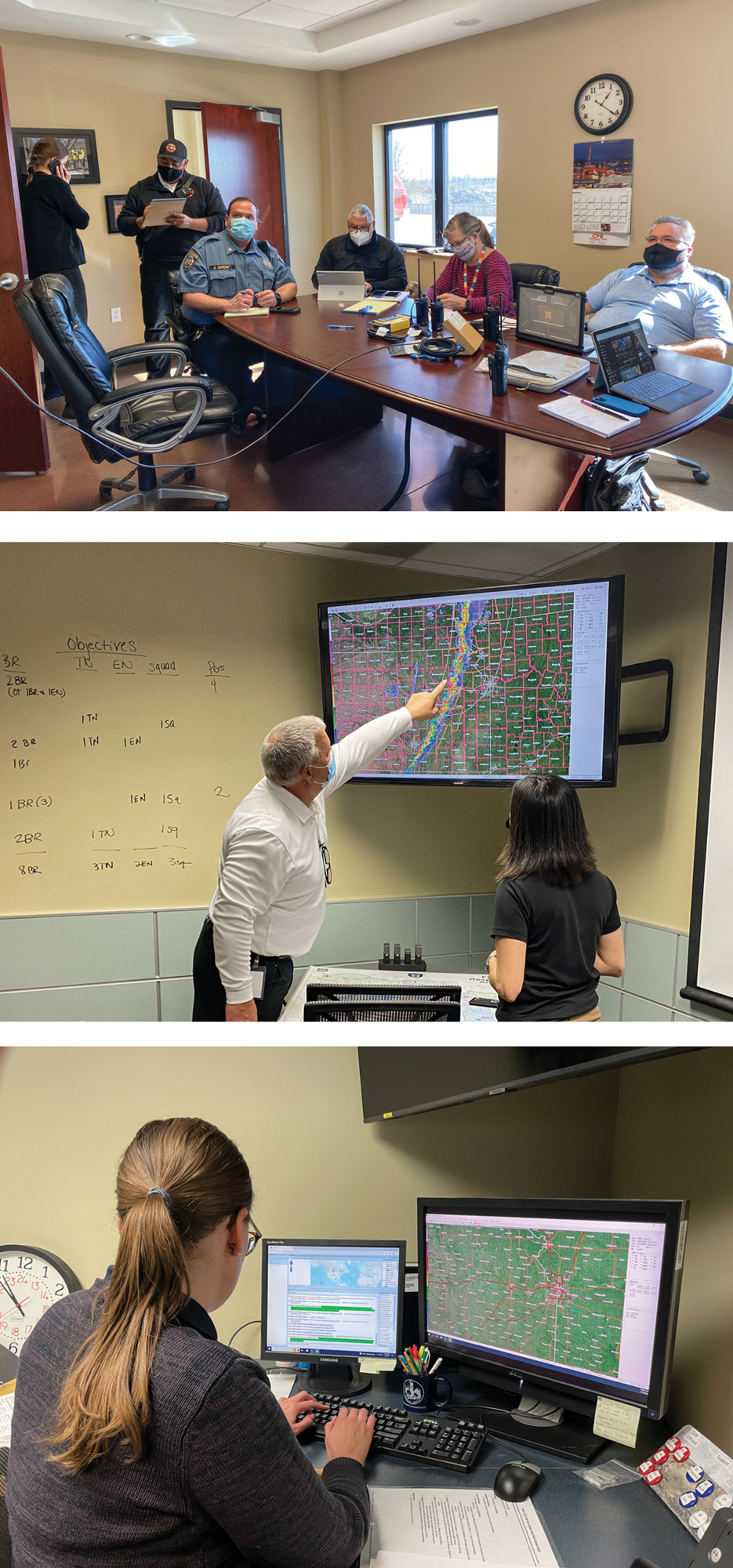

The team at work in the

Douglas County Emergency Management Center

Ideally, when an emergency occurs, local residents won’t respond in a way that looks like the old cartoons: people running every which way screaming and arms flailing.

Hoping that people respond calmly isn’t enough, though. Educating people ahead of time, providing resources for them to turn to and planning, planning, planning at the times when there is not an emergency can help ensure that chaos does not ensue.

One agency in Douglas County that unites people who spend almost every waking moment (and likely even some sleeping moments) doing all of the above is Douglas County Emergency Management (DCEM).

LOCAL MATTERS

Our Local Advertisers – Making a Positive Impact

“No one wants to think about the bad things that can happen,” says Jillian Rodrigue, deputy director of DCEM. “We do a lot of worst-case scenario planning so that our plans and procedures are better.”

DCEM staff and volunteers are not typically first responders in their planning roles. Rather, they either jump into action when a large-scale emergency happens, such as a severe weather event, or they are contacted when local first responders in the field are stressed or overwhelmed by the number or severity of emergency calls.

“We’re partners—we don’t do it to them; we do it with them, helping people understand that everybody has a role to play,” says Mike Russell, director of the department of Environment, Health and Safety at the University of Kansas (KU), and longtime DCEM board member.

DCEM assembles the support systems for any and every type of emergency that might take place in Douglas County; it has staff, technology and budget to support resources and communications that need to be deployed.

“We help the helpers. I like to say we conduct the orchestra. They know how to play the instrument, and we stay on time, putting structure over the top, with all of us starting and ending together,” Rodrigue explains.

What types of emergencies does DCEM prepare for? The short—and rather sarcastic— answer is “yes.” In other words, DCEM has formulated plans for just about every type of emergency imaginable that has the potential to happen in Douglas County, including tornadoes/severe storms; flooding; mass casualty events such as shootings or fires; large-scale power outages; hazardous materials spills/leaks; virus outbreaks; and even cyberattacks. Not all of the emergencies DCEM has plans for are negative events: The county’s NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament plans for Downtown Lawrence, for example, fall under DCEM’s purview, as did the 2022 KU National Championship parade.

“Our program is risk-based. We plan and train for incidents based here—we’re not training for tsunamis, for example,” Rodrigue says.

Jillian Rodrique, deputy director of DCEM – Douglas County Emergency Management Center

Planning, planning and more planning.

Preparedness, mitigation, response and recovery are the four traditional stages of any emergency. Because larger-scale emergencies thankfully do not occur all that often in Douglas County, DCEM staff, board and volunteers spend most of their time planning and updating plans for a variety of types of emergencies. The plans lay out detailed steps for each of the four stages, and they include precise communication tactics with backup communication plans in case of power outages or communication network outages. Plans also either mobilize resources of vehicles and people who are first responders, and/or they alert particular agencies to prepare specialized equipment or supplies for implementation or distribution.

Rodrigue says that one of the main goals for big disasters is planning to ensure continuity of operations, still providing essential services no matter the circumstances.

Staff and volunteers with the DCEM board and community partner agencies are constantly on call in case of an emergency.

“There are a lot of people on the board with the same mindset. We’re at the beck and call 24/7/365,” Russell says.

Being on alert and having people on call is not intended to generate fear or anxiety – to the contrary, Rodrigue says.

“In making these plans, we tend to regain some control. That helps to take a little bit of stress and anxiety out of the disaster. Having an action people can take allows them to take the control back,” she continues.

Protecting human life and safety, and providing information to the public about how to protect themselves shows people how to respond to a local emergency, Russell says.

“Trying to be aware of the various hazards out there, we want to inform people; we don’t want to scare people,” he says.

Once the sky clears, either literally or metaphorically after a disaster, is when recovery begins. Recovery plans can be slow to unfold, depending on the circumstances of the disaster.

“We are involved with the emergency notification and life safety, all the way through putting the trash out and informing people to be alert for scams,” Rodrigue says. “Most folks think it is done quickly, but there is an extremely long process of recovery.”

For example, some people were still in the process of recovery from the May 2019 tornado in December of that year, when DCEM officially closed out its tornado recovery plan, she explains.

DCEM looks at the lessons learned from each disaster response through the recovery process in after-action reports. Responders and managers do what is called a “gap analysis” to make sure the plan covered every potential scenario that developed. They ask themselves what the plan did well and what they were not comfortable with so they can build a template for how to respond to future similar disasters.

Interestingly, Rodrigue says the 2019 tornado helped prepare DCEM for a seemingly different emergency: the COVID-19 outbreak that began in early 2020.

“We had built a lot of relationships ahead of time, so when COVID came, we had flexed those muscles. We folded right into 2020 and had many of those same response structures being used,” she says. The idea for the COVID hub website came from the tornado, a central place for the public to look for relevant information about the emergency.

Although DCEM did not have a plan that was specific to an airborne respiratory illness like COVID-19, the agency had detailed plans for how to respond to a virus outbreak similar to influenza. In fact, they had staged drive-through flu vaccine clinics in previous years to practice mass distribution of vaccines in an outbreak. Rodrigue says the flu vaccine clinics did not look exactly like the events that DCEM eventually conducted at the Douglas County Fairgrounds for the COVID vaccines, but the flu clinics were similar enough to use as a model for the COVID clinics.

top to bottom: The Douglas County Alternate Emergency Operations Center (EOC) was activated to support first responders through the coordination of information and additional resources as they were fighting numerous grassfires in Feb. 2022. Pictured LDCFM and EM staff monitoring severe thunderstorm warnings to keep first responders in the field aware of the approaching hazard. ; An EM Staff member (Erin Huneke, Management Analyst) shares information in NWS Chat during the Statewide Tornado Drill.

The other difference between the COVID outbreak and DCEM’s influenza disaster plan, she adds, was the sheer number and variety of agencies with which DCEM worked.

“We worked with organizations and people during COVID that we never would have worked with otherwise, from the Realtor board to Just Food to the Lawrence Arts Center and many private-sector businesses,” she says. “A lot of other jurisdictions could not fathom how we came together across the community.”

Through both his job at KU and his roles with DCEM, having served as DCEM board president 10 times, Russell says he values both the cohesiveness and effectiveness of the agency.

“I’ve seen and experienced a lot of emergency management boards in the state. I’ve never seen or been involved with one that works as well as this one does,” he says.

DCEM staff and volunteers rely on information about best practices from around the country and the state to keep their plans updated and prepared. At times, local first responders and emergency managers are called upon to assist in regional disasters and vice versa. Emergency planning is a collaborative undertaking, and information is shared openly among agencies and peer networks.

Certain regions are more susceptible to more frequent disasters in certain categories, so DCEM consults those disaster and recovery plans that may apply to local situations. For example, states where hurricanes occur tend to have the best plans for things like debris management, Rodrigue explains, so it is most efficient and effective to adapt those tried-and-true techniques and practices locally.

The Douglas County Emergency Operations Center (EOC), led by Emergency Management, was fully activated following the May 28, 2019 tornado to support immediate needs from field operations and the community as well as begin recovery planning.

What’s Next?

What does the future hold for emergencies and disasters? Well, more of both, of course. With evolving technologies, politics and weather, DCEM is always analyzing new types of potential emergencies that can strike locally.

Rodrigue says DCEM is evaluating all of its disaster plans to account for the potential of artificial intelligence either being involved with or generating an emergency. Trainings and exercises incorporate new and up-and-coming technologies both for the genesis of emergencies and for the response.

“We did a field exercise last summer simulating a disaster with a hazmat transport. In the exercise, we used drones that were capable of reading the paperwork inside the cab of a truck,” Russell says. There would be no need for people or first responders to enter the dangerous and potentially fatal scene if the drones can safely access that type of information instead.

Recently there has been an increase in discussions about emergencies that result from political and civil-related violence, and how to respond accordingly, he adds.

DCEM is examining its network and processes for providing mental health services to first responders and emergency managers, as well as working to incorporate mental health support into its plans, Rodrigue explains.

Unfortunately, there is no way to keep Douglas County residents’ lives completely disaster-free.

“Emergencies and chaos will happen. How much impact they’ll have depends on our response to them,” Russell says.