| story by | |

| photos by | Steven Hertzog |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

Using data to get from question to answer, going beyond statistics to get to the win.

Changing the Scoreboard

“It is the questions and answers that matter, not the numbers,” says baseball writer Bill James in the last lines of a recent email. “The numbers are just a pathway between the question and the answer.”

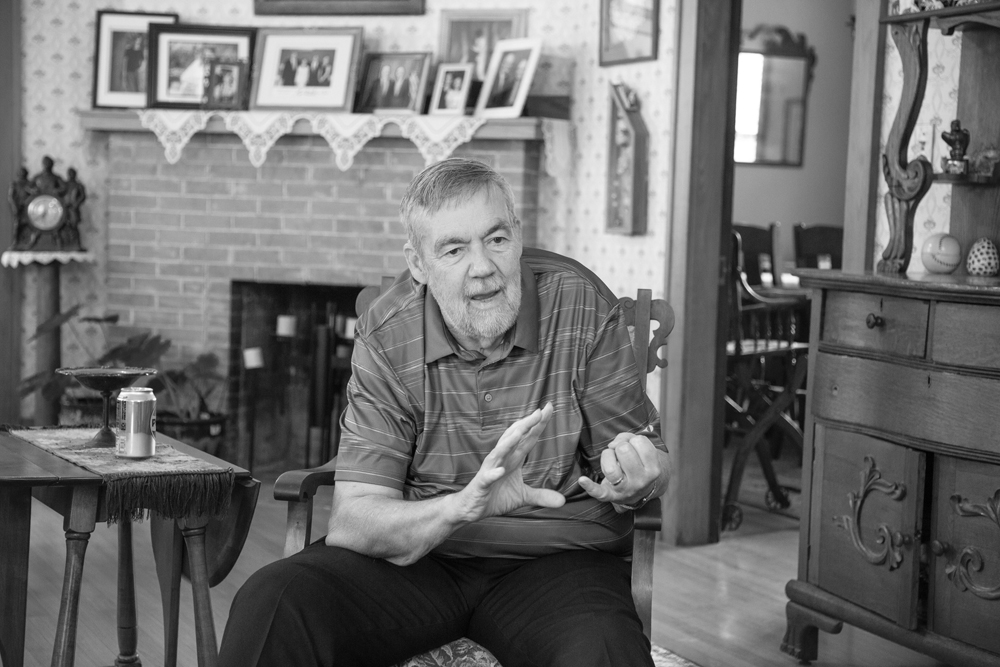

James, an influential American baseball writer, historian and statistician, lives in a well-appointed house in Old West Lawrence. A massive wooden carving of a baseball player greets us in the foyer. The nature of his work covers hundreds of articles, more than two dozen books and the ever-influential development of sabermetrics. The latter, as James puts it, is “the search for objective knowledge about baseball” and led to an entire chapter in Michael Lewis’ 2003 book, “Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game,” being devoted to James. In 2011, the film, “Moneyball,” was made based on this nonfiction book.

That search for objective knowledge, however, has changed over the years, the author says.

“When I started doing this, which is almost 50 years ago, there were really basic things that could be answered with fairly simple research,” James explains. “We’ve run through most of those—not to say that we’ve answered all of the basic questions.”

LOCAL MATTERS

Our Local Advertisers – Making a Positive Impact

Those issues most in need of research now are harder to get to, he continues. When he started using sabermetrics—detailed statistical analysis of baseball data used to evaluate player performance and develop playing strategies—the idea of asking how many runs a player had created was new, which he believes is incredible, being that would likely be the first thing people would ask about a hitter.

“The idea is to change the scoreboard, so the question is how many times does he change the scoreboard, and how much does he do to change the scoreboard,” James says. “It’s a really basic thing, and I created (and others created) simple formulas to address that issue.

“What is the relationship between runs and wins, and how many extra runs do you have to add to the scoreboard to change the win-loss record?” As he explains, it’s a pretty simple question with an equally simple answer: With nine or 10 extra runs, you get an extra win.

The issues he deals with now, however, are beyond immediate reach.

“Most of the field has devolved into smaller and smaller questions,” says James, asking, “If we move the first baseman a foot to his left, does that save us a hit a year, or does it not? It’s really important for major league teams to have answers to questions like that, because every win is worth a lot of money.”

Bill James, baseball writer, historian and statistician. Creator of Sabermetrics

Bill James, baseball writer, historian and statistician. Creator of Sabermetrics

The First Question

Additionally, he says there are people who will insist that what a player does off the field has no relevance to his value to a team, which James finds absurd. “I mean, a player doesn’t take the field and figure out how to play. All of the things that make him a major league player are done off the field and before he gets on the field.”

While James and his colleagues can’t address that issue with exact numbers, it doesn’t mean it’s not real. It’s still important, and you still have to worry about it, he says. “You still have to try to factor it into your estimates of value even though you lack any coherent, consistent way to measure it.”

All of these questions began back when James was in high school and already a rabid baseball fan, listening to games on the radio whenever possible. It was those radio broadcasts that first raised the questions he’d go on to answer later in life.

“If you listen to a broadcast, they have answers to every question, right?” James asks. “They have answers to all of those questions, and they’re happy to tell you what they are—usually several times a game. But they don’t know, they’re just making stuff up. It’s not difficult to see they don’t actually know. By the time I was 15, I was aware that the answers they were giving to those questions were inconsistent and illogical.”

In 1965, the Dodgers won the pennant with Wes Parker playing first base, James explains. Parker was a great fielder but a weak hitter. The year after that, the team signed notorious slugger Dick Stuart, and they started him some at first base, but it was a controversy as to whether that was a smart decision.

“One thing you would hear surprisingly often was that Parker’s glove probably saved the Dodgers a hit a game with his fielding, but there was a question whether he could hit enough to stay in the lineup,” he continues. “I figured that if he was an average fielder and hit the way he did, that his value was the same as if he was the hitter he was but add one hit a game, which would have meant that he was a 470 hitter.”

To James, the Dodgers debating whether they should keep a 470 hitter in the lineup didn’t make sense. As an obsessive baseball fan, contradictions like this were everywhere and not difficult to spot, so when he came to the University of Kansas (KU) and studied economics, rather than applying it to economic questions, he applied it to baseball questions.

Answering the Questions

Economics is, in part, a study of value, and to James, it’s a study of how many of X are worth how much of Y. In the case of James’ Dodgers’ revelation, how many hits is a fielder worth? How many hits is a runner worth?

“There’s an on-field economy in which the elements are not dollars and cents, but runs and hits and wins,” he says. “Basically, I misapplied my education. That’s how I got here.”

James is able to measure and create data to get to his answers because in baseball, data about games played is easily collected, and the game was extremely well-organized very early on. So the data accumulated for a hundred years before people began applying it seriously meant what would become his life’s work had a hundred years of a backlog of data.

“Since then, we’ve added a lot of data,” James admits, although quickly explaining that data collection is not the problem. “My problem is knowing what the question is and figuring out what data I need to answer that question. And then it’s somebody else’s problem to create the data.”

James’ work through the years has transformed into data that can be applied in both economic terms and in terms of who to recruit for a team. But now, it can also be used for entertainment purposes such as fantasy sports. Business and entertainment being two different things means James has to make what he’s learned through his work understandable to the layperson. How? The answer, he says, is the ubiquity of measurement.

“If I was really writing about the numbers, or if it was the numbers themselves that were important, then what you just said wouldn’t be true,” James explains. “You wouldn’t be able to apply them to both games and business. It’s the fact that it’s not about the numbers themselves but about something external for the numbers that makes them useful in both games and business.”

For example, he likens the ubiquity of measurement of how good Babe Ruth was compared to players today to the question of how high a mountain is.

“You have to have a topographical map of the quality of play,” James explains. “People won’t understand the issue itself, but they understand the concept of topographical maps. We can do the same thing about quality of play over time. We just have to study it in a lot of different ways. But you have to have a common reference point like a topographical map in order to help people understand it.”

This method of study and analysis is more a holistic approach as opposed to a data-driven approach. James says he’s not a data scientist for that reason.

“The guy who had my name—the 19th-century philosopher, William James—wrote about the way that there are questions that drop down from the sky, and there are questions that rise up from the ground,” he says. “You have to live in the middle of them, and you have to find a way to tie the knowledge that grows up from the ground to the knowledge that drops down from the sky.”

James says people think he deals strictly with knowledge that grows up from the ground, but he actually deals with questions that drop down from the sky. That misunderstanding of his work is not a new thing, he continues, referencing the line in the “Moneyball” movie about how much baseball hated him: “You’re not buying into this Bill James bull****?” asks John Poloni, played by actor Jack McGee.

“And it’s true,” James says with a laugh. “What I faced in the first 15 years I was doing this was a lot of hostility, and that hostility has pretty much dissipated over the years. People don’t resent my doing this anymore. The biggest change is the disappearance of that.”

Accumulating an Audience

When James started doing what he was doing, many people would say to him, “Well, I think what you’re doing is really interesting, but you’re never going to make a living doing it, because there just aren’t that many of us who are interested in it,” James says.

So many people told him that, but he didn’t believe it to be true, he explains, because if 50 people who you know tell you they’re interested in what you’re doing, that’s certainly something worth noting. When James started working on this concept in the’70s, Lawrence, Kansas, had a population of roughly 40,000 people.

“If one person in 40,000 is interested in what you’re doing, and you multiply that to the size of the country, then there’s a market, there’s an audience for it, and that issue is resolved,” James calculates, explaining that he believed in the existence of that audience more than anyone else did. At the same time, however, he underestimated its size by thousands.

“I knew there was an audience there, but I envisioned that audience as being a few thousand people around the country, whereas it turns out to be many, many millions,” James says, with equal parts amazement and satisfaction. “What I really did was to open the door to those people. That’s all I really did was to insist on opening that door, which people told me was a waste of time. But it wasn’t, and it turned out that there weren’t a thousand people hiding in that room waiting to get out. There were a million. That’s really what made me who I am.”