| story by | |

| photos | Douglas County Historical Society, Watkins Museum of History |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

Although started as a school to assimilate American Indians into white culture, Haskell Indian Nations University transformed into an institution that celebrates indigenous cultures.

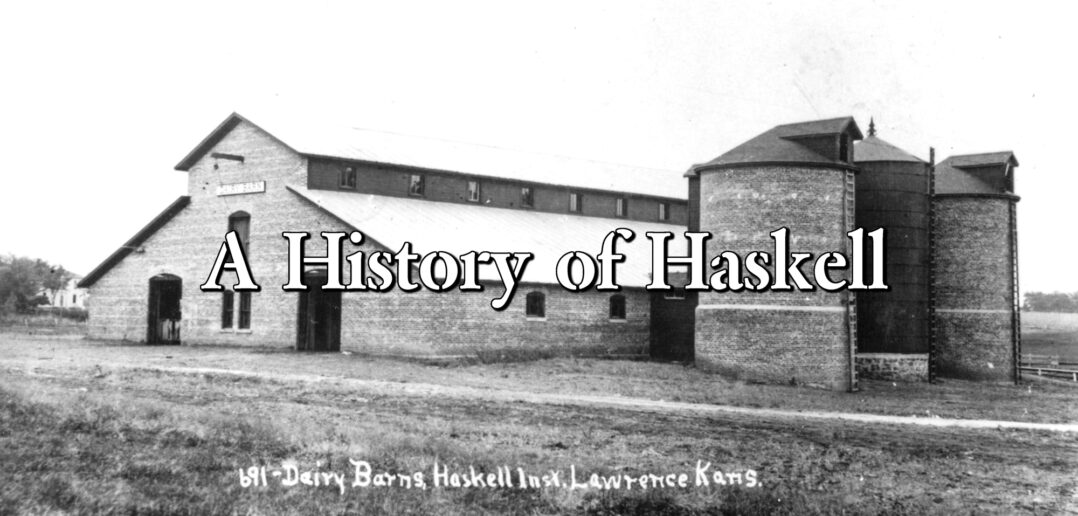

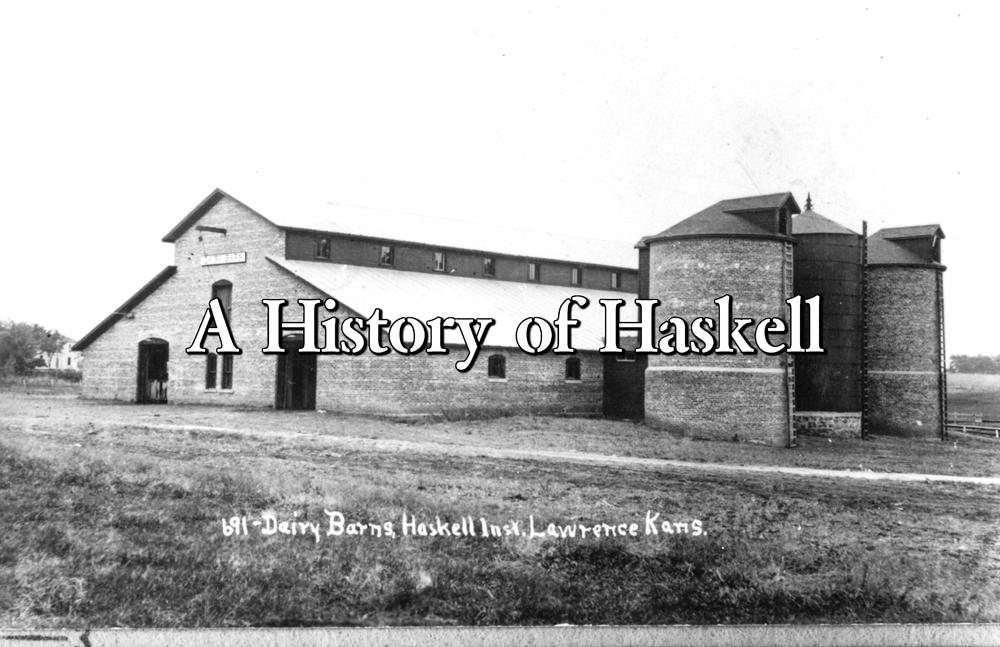

Dairy barn – Haskell

Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, Kansas, is a diverse inter-tribal educational institution. Its mission is “to build the leadership capacity of our students by serving as the leading institution of academic excellence, cultural and intellectual prominence, and holistic education that addresses the needs of Indigenous communities.” Approximately 1000 students attend the university where they can receive associate and baccalaureate degrees. The baccalaureate degree programs are Indigenous and American Indian Studies, Elementary Education, Business Administration and Environmental Science.

In the 19th century, the United States government believed industrial training schools were part of the solution to the American Indian “problem.” The government stated that it wanted to assimilate Native Americans into the mainstream (white) society and felt that education of the tribal children was the best way to accomplish this. However, the students spent most of their time doing manual labor. Little time was spent in the classroom.

LOCAL MATTERS

Our Local Advertisers – Making a Positive Impact

It is important to understand how the Europeans settling North America viewed Native Americans. They believed they were inferior to the whites and that the Europeans had a right to the land the indigenous people had lived on for generations. As European settlers expanded west, they encroached on land claimed by Native Americans. This led to a government policy of Indian removal and the establishment of the reservation systems. Tribes were resettled into areas where the environment was extremely different from where they had been living. A report dated June 30, 1885, from the Haskell superintendent James Marvin to the Commissioner of Indian Affair contained the following assessment of the students attending the school:

- In every department two points have been made most prominent: First, how to speak the English language; second, how to do any kind of work in hand quickly and well. The difficulties attending instruction can be appreciated best by those who have had the experience with youth who know little or nothing of English and who are entire strangers to all habits of industry and economy. A vague notion that necessity if laid upon them to “learn the white man’s way” is the leading thought with these youth and their friends. They have no conception of the particular subjects of study, nor of the time and effort required. On these points the parents are as ignorant as the children. Aversion to severe manual labor is not only fixed by heredity, but by prejudice, especially on the part of boys. A knowledge of letters without habits of industry cannot save the Indians.

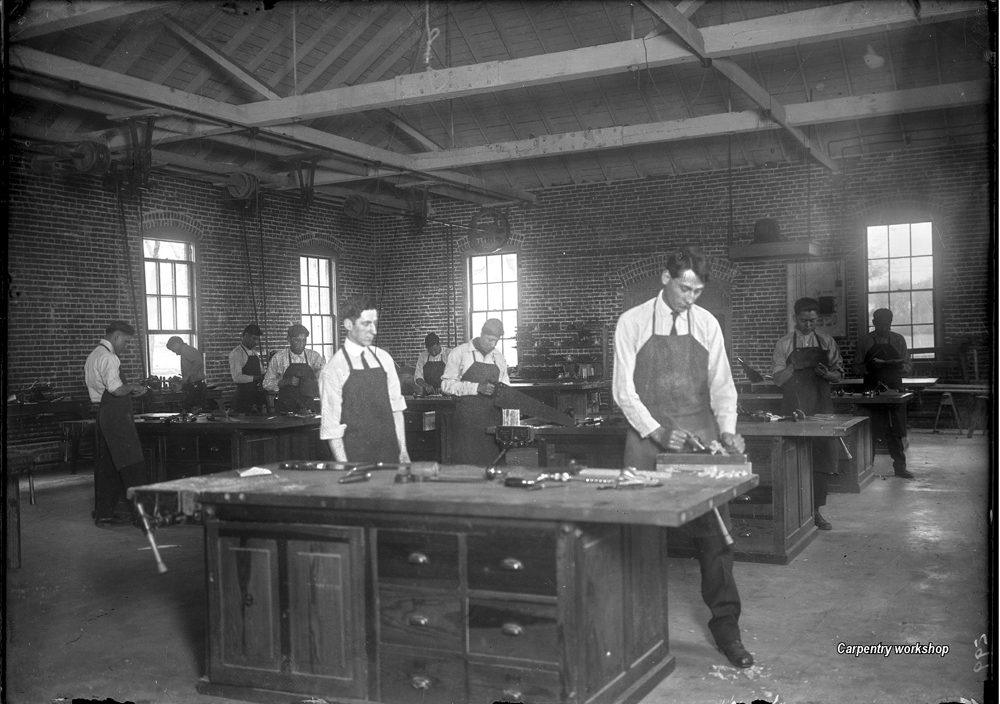

carpentry workshop – Haskell

This unfair judgement of the students doesn’t take into account that Native Americans had their own cultures and traditions of educating their youth. It does make it clear that the intent of education at Haskell and other Indian schools was to “Americanize” the young men and women attending the schools.

Haskell was founded in 1884 as the United States Indian Industrial School on 280 acres of land that was donated by Lawrence residents. When the first students arrived at Haskell, the school hadn’t opened yet and the children spent their time clearing fields, planting orchards and getting the farm and buildings ready for use. The first 22 students attended classes in grades one through five but within a year approximately 400 children lived at the school. The students, some as young as three and four years old, were treated harshly. They couldn’t speak their tribal languages or follow any of their own customs. The students were given crew cuts which ignored the custom of having long hair except when mourning. They couldn’t return home or have any contact with their families.

When Haskell opened, the campus contained three main buildings, two barns, and several other outbuildings. Crops had been planted and corrals had been built to contain the livestock. An orchard of 400 apple, pear, and peach trees had been planted.

Many students had difficulties adjusting to life at Haskell. Several students tried to return home but they received severe punishments if they were caught and returned to the school. While they plans for the school looked good in reports, students in the early years had inadequate food and clothing. The buildings were unheated and poorly ventilated leading to unsanitary living conditions. Two separate petitions from teachers and staff and from students were submitted to the Department of the Interior in 1887 asking them to investigate conditions at the school. They were concerned about the high number of sick students and student deaths occurring at the school.

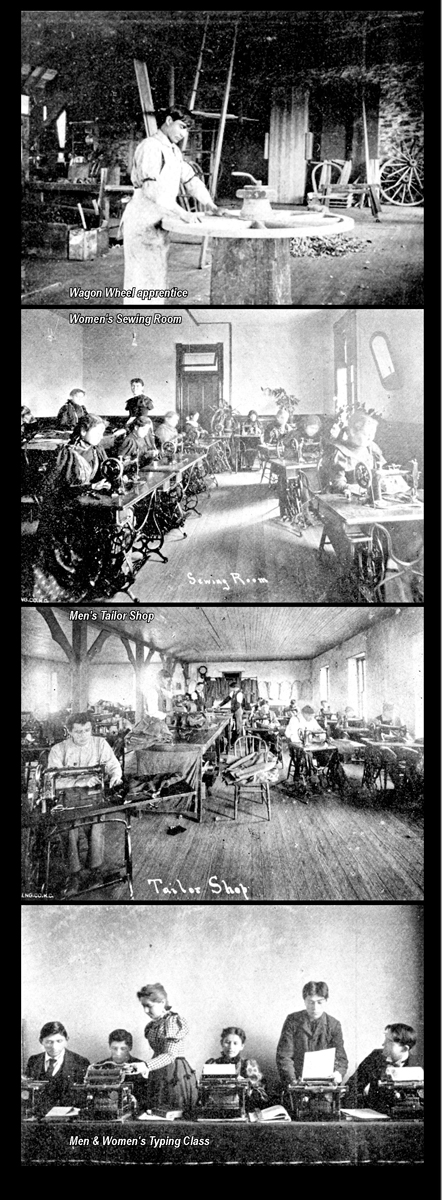

In addition to the emphasis on learning English, classes focused on manual training related to agriculture and domestic skills. The boys studied

- tailoring, wagon making, blacksmithing, harness making, painting, shoe making, and farming. Girls studied cooking, sewing and homemaking. Most of the students’ food was produced on the Haskell farm and students were expected to participate in various industrial duties.

Haskell – top to bottom: Wagon Wheel Apprentice, Women’s Sewing Room, Men’s Tailor Shop, Men & Women’s Typing Class

By 1896, Haskell offered two tracks of study—a Normal department that trained students to be teachers with the intent that they would return to their homes and organize schools and a Commerce Department that taught business skills. Haskell was accredited as a high school by the state of Kansas by 1927. The curriculum evolved to include post-secondary classes and by the late 1930s it was considered a post high school, vocational technical institution. The last high school class graduated in 1965 as the secondary education classes had been phased out. It became a junior college in 1970 and in 1992 the name was changed to Haskell Indian Nations University, reflecting its status as a 4-year college.

In 1897, The Indian Leader was introduced. It is the oldest Native American student newspaper still in publication. The first issue stated the mission of the endeavor was to share news of former students and include information about current students and teachers. In addition, the paper hoped

- to win new friends, to enter the homes of many who know but little of Indians and their capabilities, showing them that though of a different race, many of them are intelligent and progressive; that they have for their motto, “Onward and Upward” and are trying to live up to this.

The goal of learning English was met with the students writing the articles for the paper and industrial training was accomplished by setting type and printing the paper. Students working in the print shop also did job printing for local businesses and the school. The newspaper content included literary essays, updates from the Indian Service about where former teachers and students were working, accounts of the school’s athletic competitions, and news about activities on campus. By 1923, it contained information about a variety of extracurricular activities. One article described a concert by the band at Perry and others described the activities of the campus YMCA and YWCAs. The music students presented a program on American composers. It included brief biographies of the composers and selections of their work. It concluded with the audience joining in the singing. Several literary societies were active as well as other clubs.

In order to learn home making skills, the girls in the domestic science courses had a small cottage that they furnished. It had four kitchens. All the woodwork and the furniture was painted white and white muslin curtains adorned the windows. It had a guest room that contained a set of ivory furniture, a Japanese rug and blue and cream chintz drapes. The girls in the cottage also had a flock of chickens and vegetable and flower gardens.

Letters from former students reporting on their lives were printed frequently. One student who graduated from the commercial department was working as a stenographer at the Indian agency in Fort Washakie, WY. In 1923, he wrote that he appreciated the work that was being done at Haskell. He kept up with what was happening by reading The Indian Leaderand felt that the newspaper reflected the improved educational programs when it was compared to the content of the paper ten years ago. A current student wrote a friend in South Dakota about her experiences at the school and it was published in the local newspaper:

- Perhaps you would like to know where I am and what I am doing here. My school is situated about 2 miles south of the city of Lawrence. Lawrence is quite a large place itself. There are over 800 students here. They come from Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Minnesota, Arizona, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Kansas. By this you can see that the states are well represented here. We are given from the lower grades through high school. We are given a chance to take either normal training, commercial training, or home economics course, but this chance does not come until we finish the sophomore year or tenth grade. . .. Next year I intend to continue high school and take the normal course. I am a sophomore just now and if I am lucky enough to be given a choice you can be assured that I will choose to be a teacher.

As these comments from students indicate, some students appreciated the education they received at Haskell. Because the newspaper was overseen by the school’s administrators, only positive comments were published.

A visitor to the Haskell campus can see twelve buildings that have been designated National Historic Landmarks as well as several sculptures and murals. The Haskell Cultural Center and Museum is open to visitors. Several annual events worth noting are the Haskell Indian Art Market each September and a two-day Pow Wow where many graduating students wear traditional dress in conjunction with the spring commencement.

Note: I want to thank Travis Campbell, director of the Cultural Center and Museum for providing digital copies of The Indian Leader. The newspaper was an invaluable resource for writing this article. I also want to thank him for reviewing this article. His feedback helped me include some important Native American perspectives to various aspects of Haskell history.