| story by | |

| photo by | Steven Hertzog |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

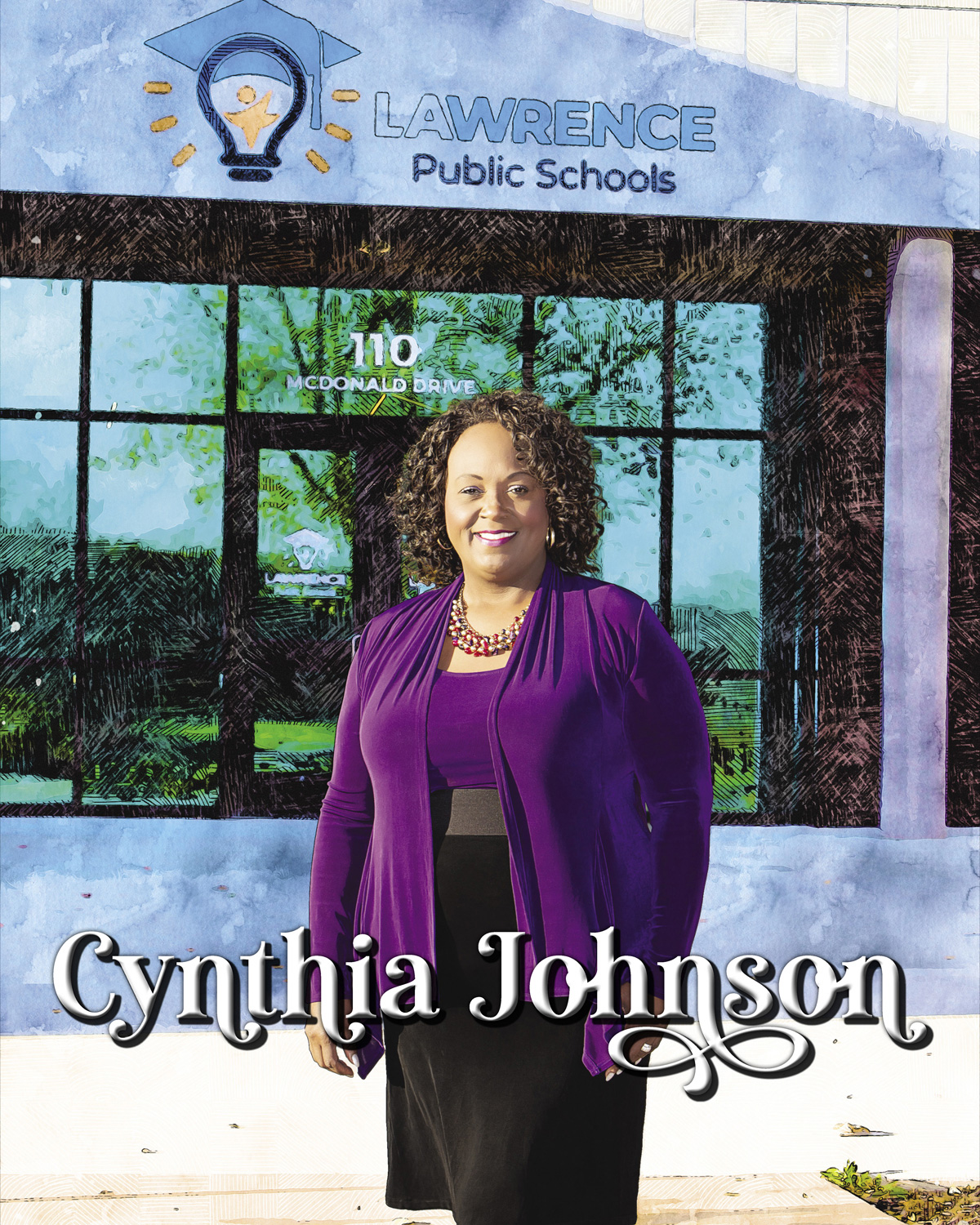

Longtime teacher and administrator, Cynthia Johnson, overcame major obstacles throughout her life and is now devoted to making sure her students thrive in their educations and ultimately reach their full potential.

Cynthia Johnson: Woman of Impact

In 1987, the Raytown School District, in Missouri, hired a new speech and debate teacher. At that time, she was the only black teacher in the building. “A lot of African American students gravitated to her because she was the first teacher who looked like us in the building,” relates Rodney Watson, executive director of Region 4 Education Service Center, in Houston. One day after school, this new teacher stayed late to work with her debate students, who had a competition coming up. She tried to get control of a classroom full of rambunctious teens, but nothing she did seemed to work. The teacher contacted each of the teen’s parents, who were less than thrilled.

“She wanted us to want it,” explains Watson, a student in the classroom that day. “There’s a time and a place for everything, and that’s what we learned that day.”

Even though this was her first job out of college, Cynthia Johnson, current executive director of inclusion, engagement and belonging with USD 497, was not one to play around when it was time to learn. The kids in her debate class learned that the hard way, but none of them ever forgot it. Four or five of those debate students remain in touch today, and they still laugh about that day, Watson says. “She wanted us to be good; she cared.”

As a child, Watson had a stutter, and Johnson helped him overcome that. He says he would not be able to do what he does today, including giving speeches regularly, if it was not for her. “She helped me work through slowing down, concentrating, giving me strategies. She’s great at seeing the potential in people, being able to bring out in people what they’re good at,” he explains. During his high school career, Watson qualified for nationals and earned a fourth-place ranking in prose interpretation.

Johnson didn’t have to dig too deep to find the passion she needed to help him. She also stuttered as a child. It was so bad at times that people could not understand her. “My mother taught me how to sing to overcome stuttering. I always say that God gave me my voice as an instrument, but Mama taught me how to use it,” she says.

Watson’s parents died four years ago, his mother soon after his father. Unbeknownst to him, his mother had called Johnson several months before she died to ask her to help her grandson (Watson’s son), who had just started in speech and debate. She said to Johnson, “Help him the way you helped Rodney.” She promised his mother she would.

A Seat at the Table

In 2019, Anthony Lewis, superintendent of Lawrence Public Schools, asked Johnson to visit the district, after which he offered her the opportunity to serve as interim principal at Lawrence High School (LHS) and co-lead the seven-phase construction/renovation project, a significant part of the $87-million bond issue Lawrence voters approved in 2017.

“LHS marked the fifth multimillion-dollar construction project I co-led during my professional career,” Johnson explains. The five projects together totaled approximately $140 million. “Having a seat at the table during construction allowed me to serve the LHS students, staff, families and the community. Creating an environment for the Chesty Lions’ students and staff to learn, teach and grow was important.”

After much positive feedback from colleagues, students and parents about her leadership during this transition, Lewis asked Johnson to stay on the next year to continue to help them through completion of the construction.

Overcoming Obstacles

Although her childhood was full of faith and love, Johnson grew up in extreme poverty; the water and gas were turned off often. Her family had a small kerosene heater to keep the house warm, but it did not work well. At the beginning of each month, she would go with her mother to stand in line for food. “My family didn’t have much financially,” she says. “However, we had a love for one another and others. Also, our faith in God is what sustained us from day to day.”

One thing Johnson wanted as a child but never obtained was a box of 64 crayons. At the time, they only received eight crayons on the welfare system. “I thought only the rich, white students had the boxes of 64 crayons with the sharpener on the back,” she remembers. “Although my family could not afford this item when I was a child, I made sure to purchase a box when I became an educator. To this day, I always have a box of 64 crayons on my desk to remind me of my journey of overcoming obstacles.”

Johnson’s parents were bused 60 miles a day to C.C. Hubbard High School, in Missouri, because of the color of their skin. Segregation kept them from attending a high school with others who didn’t look like them. “I was blessed to become an administrator years later at the same school they could not walk in front of,” she explains. “I proudly walked down the halls for my parents and others who could not attend that school in the past.”

As a child, her father taught her how to kneel and pray, and her mother taught her how to sing to overcome her stuttering. “My parents knew that if I could pray and sing, I would always have a prayer in my heart and a song on my lips,” she says.

Johnson looked up to activists who lived and served during the Civil Rights Movement. “Rosa Parks was my favorite hero. Because she sat down on Dec. 1, 1955, and refused to give up her seat. Because of what Mrs. Parks did on that day in December, I was able to stand up years later and am still standing today.”

In 1977, when Johnson was in seventh grade, her English and drama teacher, Ken Bell, asked her to join speech and forensics. “At first, I thought he was crazy because I stuttered badly and was quiet in class,” she explains. He gave Johnson her first script, “In White America,” by Martin B. Duberman, a documentary about what it is like to be black in white America. “One of the excerpts in the story … is the story of how Elizabeth walked through the taunting crowd as she tried to make it to Central High School … ” she says. “This scene was why I fell in love with the historical perspective of the Civil Rights Movement.”

With Bell’s help, Johnson went to her first competition, held at the same school her parents were not allowed to attend, and won first place.

This experience led her to become a forensic teacher, coach and professional speaker. “The ‘In White America’ script was one that I began reenacting in junior high school, and I still reenact this scene … today.”

Reach, Teach, Lead and Succeed

Johnson earned a bachelor’s degree in education and speech communication, theater and special education from Central Missouri State University. She also earned a master’s of education in secondary administration and a doctorate in educational leadership, concentrating on school connectedness, building relationships and closing the academic/achievement gap, from Baker University.

She’s served 35 years as a high school speech, forensics and special education teacher; middle/high school principal, elementary principal leadership coach and district-level project leader in Missouri. She has also worked as an independent national educational consultant, facilitating professional development in more than 40 states.

During her very first job at age 14, working at Central Missouri State University as a cafeteria worker, Johnson was sure she was going to continue down this path. “I had watched my parents work at the university … but God had a different plan for my life,” she says. Today, her career path is still about service, as it was back then. But when she visits schools, “I always visit the cafeteria staff to tell them what they do is essential so I can remember where I started.”

Johnson’s current role with USD 497, executive director of inclusion, engagement and belonging, is a combination of her life’s work. She works with the Executive Leadership Team, Native American Student Services Coordinator, Mental Health Coordinator, Lead Principals, Teaching and Learning Department, building principals, educators, students and families. Her main focus is to lead the district equity work, which includes ensuring all students have access and opportunities, and are representative of all populations so they can reach successful outcomes.

It has provided Johnson yet another opportunity to reach, teach, lead and succeed with today’s youth, she explains. “My role as an educational leader is important to the community because the students in our schools today will be the same ones living and working in our community tomorrow. There is no greater joy than working with children of all ages and seeing them become adults.”

“She works very well with children of all ages,” says Bruce Kerr, commissioner on the board of Platte County, Missouri, retired highway patrolman and former colleague of Johnson’s. He believes it’s her goal to give them the best of herself and to make each child feel valued and supported in their educational endeavors. “Johnson is always helping other people, and it’s important to her to always help somebody else whenever she can. She cares very much for others, and again, whatever her hands seem to touch turns to gold.”

“Yes, I can!”

For Johnson, not everyone has been supportive along her journey. At 5 years old, Johnson remembers teachers starting to talk about her stuttering. The older she got, the more they talked—about her inability to read aloud, being placed in special classes, living in poverty. “Many people liked me but didn’t believe I would ever achieve anything,” she says.

They said she wouldn’t make it because she came from impoverished conditions, she says. Because she stuttered so badly one could hardly understand the words that came out of her mouth; because she couldn’t read aloud until the fourth grade and struggled with reading throughout high school; because she was placed in special classes until the 10th grade even though she begged to attend “regular” classes. “Everything around me seemed to say, ‘No, she can’t,’ and ‘No, she won’t.’ But I stood up one day and said, ‘Yes, I can, and yes, I will!’

“My greatest accomplishment is not believing what others (educators and classmates) said about me growing up,” Johnson explains. “Earning a doctorate was to show me that I didn’t have to live down to the level that people thought about me.”

Still today, she faces obstacles, but the way she views them and handles them has changed. “When people try to impede my journey because of the color of my skin, those who are intimidated by a strong African American woman, and those who try to make me feel inferior or less than others: None of these obstacles have stopped God’s plan for my life,” she says. “I have learned to turn obstacles into opportunities with my faith in God.”

Johnson loves spending time with her husband of 28 years, reading the Bible and Christian literature, and listening to sermons, inspirational speakers and gospel music. She volunteers as part of her ministry to encourage others through singing. “I share my gift of singing with those who are sick and shut in, those in the hospital and those who may need help but don’t know how to express it,” she says. “I love all types of music, but the church’s hymns bring me tremendous peace.”

Spreading Hope

Johnson has no children of her own but feels she has been blessed with a heart to love all children. “My students have always been like my children,” she says. “My nickname is ‘Mama J.’ This is a name given to me by students during my student teaching and is still how students refer to me today.”

She sees her role as building relationships with students, helping them learn the essential skills to be fully equipped to navigate their futures and letting them know they have the power to be great. She believes if students turned this idea into action, they would unleash their power to reach their highest level.

“I describe myself as a woman with a message of hope. Hope awakens the spirit and nurtures the soul. Hope keeps you moving forward when the world’s pressures try to hold you back. Hope gets you through the tough times when you want to give up. Hope gives you something to look forward to even when you don’t know what to do. Hope lifts a bowed head when despair tries to steal your joy. Hope is what I have for students as they transition from the different grade levels and through this life,” Johnson explains.

She says she loves lifting students to a higher level. “As educators, I believe we have the power to lift every student.” What she does not like about what she does in education is witnessing others wound the spirits of children. “For some youth, school is the only place they can feel as if they belong.”

Felecia Andrews, business/career education teacher with Hickman Mills Schools, in Missouri, and Johnson’s colleague, agrees. “When I think of Cynthia ‘Mama J’ Johnson, I think of a phenomenal woman, full of faith, love and hope. She has a passion for learning and … educating others, letting them know that there is no learning goal that cannot be reached, no matter what obstacles they face. ‘Mama J’ is not just a name but a term of endearment, and she inspires every person she encounters.”

Johnson says her passion is speaking life into students and helping them reach their full potential and purpose. “I envision myself serving in the educational arena as long as God gives me the strength to do so. My journey includes multiple avenues to use all that God has given me to help others, especially youth. There are students in this world who still need a ‘Mama J.’”