| story by | |

| photos by | Steven Hertzog |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

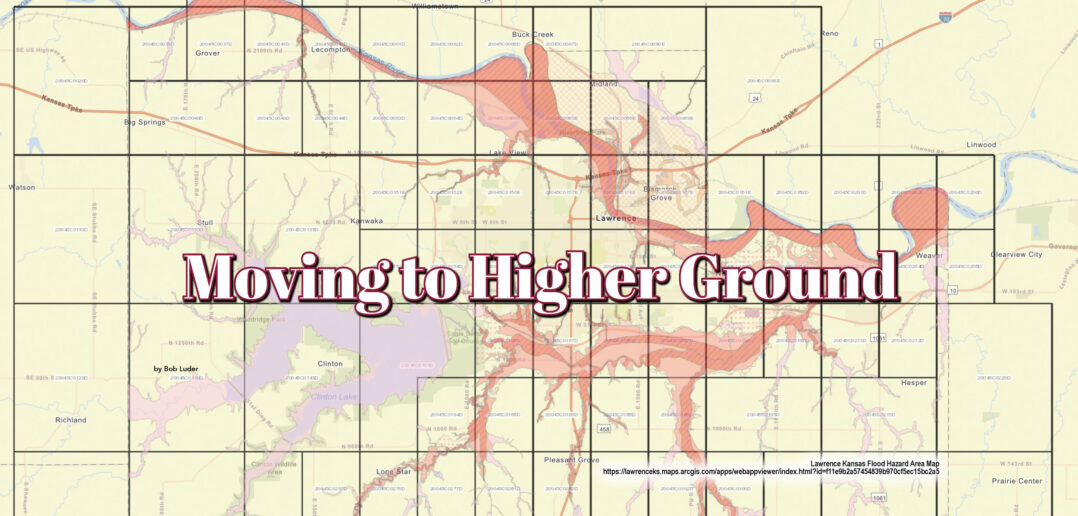

Expanding west in Lawrence moves residents and businesses out of flood zones, and a combination of new development and infill may well be the ticket for Lawrence moving forward.

Lawrence Flood Hazard Map online here

When it comes to the growth of communities through the years, the general trend has shown cities growing toward one other, melding together. Think about it. Anyone who’s made the drive between Los Angeles and San Diego finds it hard to differentiate ever coming out of one city and into the other. The Denver/Colorado Springs/Fort Collins corridor on the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains has become one huge metroplex of civilization. And don’t even get me started on the I-95 corridor in the northeastern part of the country.

Then, there are the shifts in landscape and population of Lawrence as it pertains to the Kansas City (KC) metropolitan area. While Kansas City certainly has lived up to its side of the deal with expansion into western suburbs like Shawnee and Lenexa, Lawrence, which has prided itself in taking countercultural stances with the rest of the state in many aspects, has gone the other way. Instead of spreading city development east and making Lawrence/Eudora/DeSoto/Shawnee/KC its own metroplex, from the late 1970s to today, Lawrence has grown west, away from the KC metropolis.

Why? It turns out the answer lies in the simple lay of the land.

“Lawrence expanded west because it was easy,” says Price Banks, a retired Lawrence attorney who was the city’s planning director from 1982 to 1994. “To the south, you had the Wakarusa River. To the north and east, you had the Kansas River and lowlands. Out west was high land. You could more easily put services in. Engineers liked it. It was easy to put infrastructure in.”

It’s as simple as that. Lawrence has learned the hard way throughout its history that there are areas north, east and south of the city that are prone to considerable and damaging flooding during severe weather events. The worst flood in the city’s history occurred in 1951 and caused $3 million in damage, and nearly decimated all of North Lawrence. In 1993, the levees and reservoirs built following the 1951 flood did their jobs, but flooding still resulted in $1.2 million in damage and $5.8 million to surrounding areas left unprotected.

In more recent times, heavy rains have caused the banks of the Wakarusa to overrun, and floodwaters have reached as far north as 23rd Street and beyond.

“Going east has always been a little difficult because of the Wakarusa River and floodplain,” says Jeff Crick, director of Lawrence’s Planning and Development Services. “That area of the Wakarusa blooms and gets wider south of town, and the floodplain blooms down on that side of things.”

By contrast, the west side of the city, which, prior to the 1970s, stretched no farther than Kasold Drive, featured rolling, wooded terrain that proved to be a developer’s dream. As soon as one certain local developer pitched a public golf course to the city in the 1960s, and the city committed to providing infrastructure to support it, it seemed there was no stopping Lawrence’s march west.

Teeing Up Development

“I’d say the entire area was heavily influenced by Bob Billings,” says Brian Kubota, who founded Landplan Engineering in 1978 and helped develop and design the landscape for many areas of West Lawrence.

Billings, a former University of Kansas star student, basketball player and employee, teamed with some friends, purchased 460 acres of undeveloped land west of Kasold and between 15th and 23rd streets, and built Lawrence’s first public golf course, Alvamar, in the late 1960s (the course opened in 1968). Almost immediately, the 7,485-yard, 18-hole, par-72 layout attracted widespread attention with its zoysia fairways and tee boxes, and immaculate bent grass greens.

Golfers came from all around—mainly Kansas City and Topeka in addition to locally—to play, and the increased traffic quickly increased adjacent land values. That led to the development of homes and neighborhoods surrounding the golf course. The increased residential population led to commercial development.

West Lawrence was off and running. The 1980 opening of Clinton Lake exacerbated further development, and the opening of nine miles along the west side of the South Lawrence Trafficway in 1996 (the full trafficway opened in 2016), making for more easy access to Interstate 70 to Topeka or Kansas City, pushed activity even farther west.

“Alvamar caused a lot of infrastructure to be built,” says Kubota, who came to town in 1969 as city planner and landscape architect for then-City Manager Ray Wells. “The water main along the trafficway. There’s a new water plant and main sewer line.”

Indeed, the infrastructure spurred by the development of Alvamar was the most key aspect of Lawrence’s expansion. And the most expensive. A second water-treatment plant came online south of the city, as did a second sewer facility, all large civic investments.

“Having that plant allows for growth,” Crick says. “Streets, parks, fire coverage … . Constructing is one cost, but maintaining this infrastructure over the years is another.”

For example, Crick says a “water pressure zone” west of Kansas 10 would come at an estimated cost to the city of approximately $12 million. Future projects extending Bob Billings Parkway and West Sixth Street are estimated to cost approximately $18 to $19 million. Sewer-line alignments for future developments in West Lawrence would likely cost around $22 million, and some of the cost would be covered by the developments.

“Residential goes where it wants in many aspects,” Crick says. “All require infrastructure and connectivity.”

As much as Lawrence has expanded in recent decades, it might not be enough to accommodate the annual influx of newcomers wanting to call it home. Roughly 1,000 more people move to the city each year, Crick explains. The city typically issues 140 to 150 single-family residential permits each year. About double that number is needed to handle the influx, her adds.

“We’ve seen a lot of permit activity in the southeast part of town,” Crick says. “There’s also a lot of infill development closer to downtown. And another cluster out by Rock Chalk Park.”

Regardless of recent trends, West Lawrence will always be an attractive and sought-after section of Lawrence for aspiring residents, both young and old, single and families.

“Some people say West Lawrence doesn’t feel like Lawrence,” Crick says. “But I think it does. It just has its own feel.”

How the Future Looks

Kubota, who planned a lot of the streets in West Lawrence and developed with Jeff Hoffman the Villas at Alvamar and The Cove, says he foresees two areas prime for development in the coming years.

One is a section of land just west of the South Lawrence Trafficway and north of Clinton Lake State Park, stretching from south of Bob Billings Parkway up to U.S. 40. That land has a high ridge running through that makes it good for stormwater drainage, and the Wakarusa Wastewater Treatment Plant is close enough to serve it. Another is ground adjacent to Lawrence Nature Park and Martin Park, about a half-mile north of Free State High School and east of Rock Chalk Park.

Attorney Banks, for one, agrees with Kubota’s assessment.

“I think there will be more growth north and west,” he says. “The utility folks have spent a lot of money buying land and expanding capabilities. Development is going to follow that.”

However, Kubota points out that he wouldn’t be surprised to see Lawrence’s expansion, especially westward, slow some in the near future.

“The city hasn’t been very aggressive on growth,” he says. “Some of that has to do with the politics of the City. There is a lack of affordable housing. But the counterpoint to that is land prices have gone up. A lot of people now are buying the land as an investment and not developing.

“I think the city is ready to take off again, but it needs another Bob Billings.”

Crick says the current trend he’s seeing is more toward infill development—tearing down or adapting older, existing structures closer to downtown and redeveloping that land, or finding what little available ground exists near the city’s core and developing that.

“Today, we’re seeing trends of people wanting to be back downtown,” he says. “People want walkability in shopping and entertainment, eating. People tell me they like to live downtown to have a sense of Lawrence. More people are retiring to Lawrence, and they’re wanting to be down where a lot is going on.”

As far as Banks is concerned, a healthy combination of new development and infill is just the combination Lawrence needs.

“Because of land being scarce and utilities being expensive, we’re seeing more infill,” he says. “It’s how you want it as a planner. You want to fill in the gaps.”