| story by | |

| photos by | Steven Hertzog |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

Stormwater issues are top of mind and a constant concern in Lawrence, especially with the Kaw River running through town and threats of climate change.

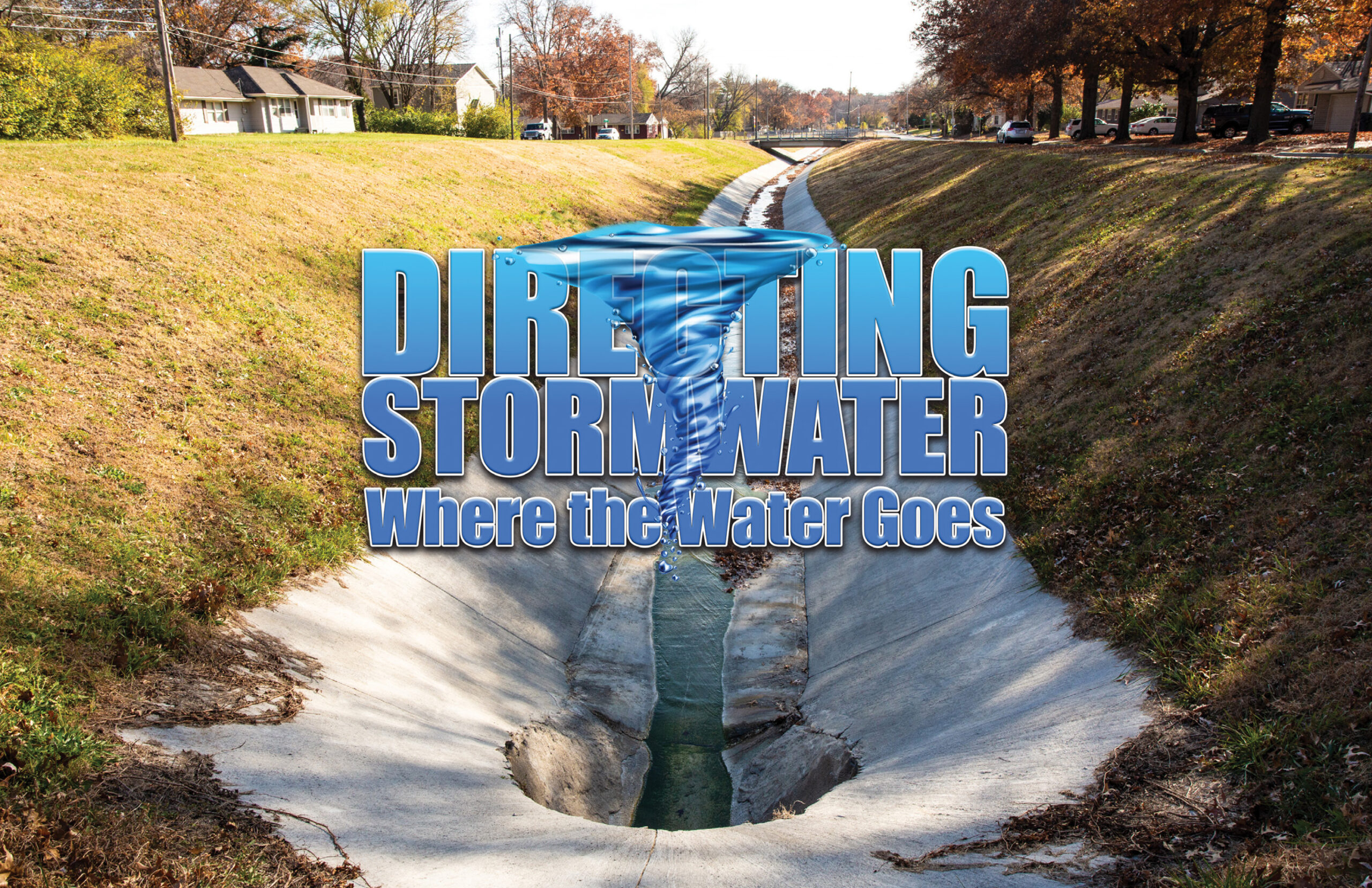

Directing Stormwater – Where the Water Goes

Matt Bond read about and studied in depth the 1951 Kansas River flood that fully submerged North Lawrence under 8 to 10 feet of water between the north and south sides of the railroad tracks, decimating the area for residents and businesses. He lived through the back-to-back, 300-year rain events in 1993 that caused river levels to come to within 6 feet of the top of the levees built following the ’51 flood and, again, caused major flooding to the area.

He recalls seeing automobiles on 23rd Street near Naismith Drive stall in high water as the floodplain filled during another deluge. He saw photographs in the local newspaper of residents paddling canoes down Alabama Street, south of 19th Street as the street turned into a raging river.

“I would like to make sure that doesn’t happen again,” says Bond of the latter event, but he might as well be referring to them all. As engineering program manager of the City of Lawrence Municipal Services and Operations (MSO), one of Bond’s job requirements (he also inspects 27 bridges in the city) is to control as best as possible the city’s stormwater and where and how fast it flows so as to cause as little damage to infrastructure and land as possible. He oversees a vast assemblage of lines, pipes, gutters and channels, ensuring they remain up-to-date and smoothly working to hold back stormwater from Lawrence’s door.

“We maintain all storm sewers,” Bond says. “We perform upkeep on what we have as well as designing new infrastructure all the time.”

He says the increasing effects of climate change have only intensified the challenges of his job.

“Lately, we’ve been having more intense storms over a shorter time on a more frequent basis,” Bond says. “Back on April 28 (of this year), we documented 2.17 inches of rain in 25 minutes at a pump station near Vermont Street.

“We’ve started an asset management project … . We’re identifying everything we have in the ground and inspecting it. We have things built 50, 60, 70 years ago. We know they’re there, but we don’t know the size or condition. Anything older than 10 years, we’re going to stick a camera down there and inspect. We’ll build our next capital-improvement projects off of that.”

The city’s stormwater utility was started in 1996. At that time, 11 of what they classified as “Phase I” projects were identified, Bond explains. Seven were completed. Currently, he says his department has completed 17 of 41 identified projects.

“We reassess the (capital-improvement) plan every year,” he says. “There are some issues we need to address. I’d say, overall, Lawrence does better than most (comparable cities). But, we have some work to do.”

Repairs to the Bowersock dam and The Kansas River

Stormwater Defined

Ted Peltier, professor in the environmental engineering program at the University of Kansas (KU), has spent much of his professional life studying stormwater and its effects on Lawrence and the surrounding communities. When it comes to defining stormwater, he prefers to keep it simple: Stormwater is anything ending up on ground surfaces following rainstorms.

What to do with stormwater, Peltier says, is all about managing the flow and directing it to where it needs to go to cause the least amount of damage and provide the greatest benefit.

“Sometimes, we try to do a little treatment along the way,” he says. “Remove solids, things like that. But most important is controlling flows.”

Peltier believes Lawrence has been more active than most of its peers in being proactive in stormwater flow control.

Repairs to the Bowersock dam and The Kansas River

“It’s structure that’s been built up over time,” he says. “It consists of older and newer parts. The city has updated code several times to upgrade approaches to stormwater removal. There’s a good deal of pollution prevention involved. They’re trying to do whatever they can.”

Though the Kansas River has had flooding issues in the past, Peltier stresses the city is fortunate to be located next to a major waterway like the Kaw.

“It’s a place where stormwater can go,” he says. “Impacts are less because there’s more space for water to move.”

Much of Peltier’s study and work the past seven or eight years has been on ways to improve the quality of stormwater. Specifically, he’s been studying stormwater runoff from rural fields in western Johnson County. He’s also been involved in research regarding the Coblentz Marsh, a man-made, 160-acre wetlands area in the Deer Creek Wildlife Area, near Clinton Lake. Stormwater runs through the marsh, into the wetland and into the Wakarusa River before depositing into Clinton Lake.

“We’re looking at how having water run through the wetland can affect solids as well as nitrogen and phosphorus,” Peltier explains. “If we can slow down the flow, it’s easier to separate solids, because they’re heavier.”

Water quality—that is, keeping water volume moving while keeping it cleaner—is one of two big issues facing the handling of stormwater, he says. The other is growth within the city. More industry, businesses and homes leads to more concrete, which absorbs less water and takes the place of areas once used to steer runoff and flow.

A third issue, Bond points out, is the changing climate.

“Most modeling shows that weather will be less predictable,” he says. “There will be more big weather events, more intense rainstorms. That will make stormwater more challenging.”

Past, Present and Future

During the great flood of ’51, 410,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) of water was measured coming through the U.S. Geological Survey gauge in the Kansas River near DeSoto. As a result of the massive flooding that occurred, Bond says, the Kansas River Levee was constructed. The 11.5-mile-long unit consists of a levee along the north bank of the Kansas River as well as the Mud Creek Levee along the south bank of Mud Creek. It runs from Jefferson County, through Douglas and into Leavenworth County.

Lawrence was the first community in Kansas to have its levee certified by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and second in FEMA’s Region 7, which includes Iowa, Kansas and Missouri.

Over the years, there also were seven flood-control reservoirs dug out upriver from Lawrence that also captured stormwater and helped ease flood risk: Perry Reservoir, Tuttle Creek Lake, near Manhattan, Milford Reservoir, Glen Elder Reservoir, Kirwin Reservoir, Webster Reservoir and Wilson Reservoir.

“The levee was constructed to handle 283,000 csf,” Bond says. “The greatest I’ve seen it is 190,000 csf. That was when water reached within 6 feet from the top of the levee in ’93.”

More recently, he has been working on a study of the Jayhawk Watershed, a main stormwater sewer line that runs diagonally from near Memorial Stadium on the KU campus to the Kansas River. The main trunk line conveys most sewer water to the river.

To this day, Bond says major rain events can put the northwest corner of Watson Park, at Seventh and Tennessee streets, completely underwater.

“I’ve seen water almost up to the lower links in the basketball netting on the basketball courts there,” he says.

Bond says the current study is looking at removing existing pipe along that line and replacing it with larger pipe to alleviate water flow through the Jayhawk Watershed. It’s a difficult task, he says, because of the way the pipe weaves diagonally through neighborhoods, often between residential homes.

“We’re always looking at ways to do things while minimally disrupting peoples’ lives,” Bond explains. “We’re trying to do a better job with public involvement. The biggest thing is telling the public why we’re doing the project.”

The Jayhawk Watershed line is what in stormwater engineers’ jargon is termed a “closed conduit.” Stormwater is also controlled through open channels, such as the channel recently relined between the north and south lanes of Naismith Drive just north of 23rd Street. And there’s the ongoing work at 17th and Alabama streets to ensure no more canoers get pictures taken.

“Typically, we start projects downstream and work our way up,” Bond says. “We try to take a more corridor approach. If we’re going to fix the storm system, then what about pedestrian ramps? The goal is to deal with as many issues while we’re there so as not to disrupt life around the site.”

Lawrence also has several areas throughout the city designated as floodplain, low-lying areas that can be major conveyances of water during intense storms.

“Lawrence has quite a bit of floodplain because of the Wakarusa River,” Bond says. “Floodplain helps syphon out contaminants from stormwater.”

He adds that floodplain often gets filled in by development, though Lawrence has a no-rise policy—filling in floodplain can’t result in a rise in stormwater during flooding situations. There has to be another means created to drain stormwater from the area.

Though it has more modern stormwater infrastructure, Bond says there is always work going on in West Lawrence, though typically with the bent of a different color. There’s a planned project near Arrowhead Drive where concrete channeling will be removed in favor of replacing it with something that’s more “green,” adding conservation areas designed to contain more runoff, using more retention ponds or wetlands areas.

Matt Bond overseeing the work being done at the Dam and River

Bond thinks a good part of stormwater’s future will be dealt with using green initiatives.

“I think we’re going to see more green innovations,” he says. “If you’re trying to promote green infrastructure, you can pick up stormwater in rain barrels or storm gardens. One inch of rainfall over 500 square feet can fill a 55-gallon barrel.

“There are also pervious pavements, which absorb rainwater and improve the quality of stormwater, because it absorbs slowly and removes solids. There are other things like grass roofs and native grasses. These all are things being tried now, and I’m sure more innovations will be coming in the future.”

![]()