| story by | |

| with personal account | by Janet Faust |

| photos | Douglas County Historical Society, Watkins Museum of History |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

Though enjoyed by Douglas County residents now, the original Clinton Lake Dam project displaced the residents of many early towns that ultimately disappeared.

Photo by Dwayne Juedes (Left to Right) Karla Gerisch, Leita Moore, Ellen Gerisch, Edna Moore and Doug Gerisch shown here in front of the United Brethren flChurch, wade through 1965 Wakarusa River flood waters in Richland.

People growing up in Kansas today are familiar with numerous lakes created by damming rivers to aid with flood control. The first was Kanopolis Dam on the Smoky Hill River in Ellsworth County, completed in 1948. Since that time, more than 20 dams have been constructed in Kansas by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The construction of Clinton Dam was completed in 1977. It was built to control spring flooding in the Wakarusa River Valley. What existed under the water before the dam was built?

Three Douglas County towns—Belvoir, Bloomington and Sigel, as well as Richland in Shawnee County—existed in the area that was flooded to form Clinton Lake. Thousands of acres of farmland were also covered by water as the lake filled behind the dam.

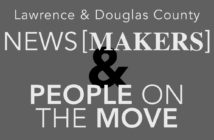

Top to bottom: Richland Main Street courtesy of Herb Orr [In the 1960s before being bought out by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Richland main street business district included Georgia Neese’s General Store (Richland Shopping Center), Fred Van Nice’s Hardware, Clara Morgan’s Richland Café, Wolf’s Gas Station and Tom Bame’s Barbershop.]; Scott Kirkham Store at Clinton; George Washington Family of Bloomington. photos courtesy of Wakarusa River Valley Heritage Museum

Belvoir was located on the Santa Fe Trail route in 1855 and was approximately 13 miles southwest of Lawrence. A number of settlers established homes and farms in 1855 and 1856, including H. Heine, James Dun, M. Clayton, R. A. Dean, H. McKenzie, A. S. Baldwin, A. E. Northrop, J. Huize, D. Dack and a Mr. Smith. A post office was established in 1868, and L. D. Bailey was named postmaster. St. John’s Catholic Church was established in the area in 1856. The Carbondale branch of the Union Pacific Railroad was built 2½ miles from Belvoir’s first location, so the post office was moved to the railroad. A new schoolhouse and other improvements were completed, and the existing businesses in Belvoir moved to the new location. The post office was closed in 1903, and by 1910, the population of Belvoir was 30.

Bloomington had the shortest life of the three towns and existed for only a few years beyond the Kansas territorial period. It was settled in June 1854 but was not called Bloomington until Harrison Burson applied for a post office. He was successful, and Bloomington had a post office from July 1855 to August 1858. Within a year of the first settlers arriving, the area had a population of over 500 residents. Settlers were Free State supporters, and a branch of the underground railroad operated in the community. Local legend has it that Bloomington was a black community that had been settled by Civil War veterans. This is not documented because it is difficult to check census records without knowing names and because Bloomington’s prime was reached in the territorial era. In 1857, the north half of the community moved to a new location, and the remaining portion of the community was renamed Winchester. Bloomington became an incorporated city Feb. 16, 1857, and Winchester was incorporated a few days later as the town of Clinton.

Bloomington and Clinton ultimately became fierce rivals. Bloomington had a brief chance for fame when the delegates to the Topeka Constitutional Convention were voting to determine the location of the capital of Kansas on Oct. 23, 1855. Bloomington received four votes on the first ballot that included nine other communities. The top two choices for the second ballot were Lawrence and Topeka.

Sigel, or Sigel Station, was located on the St. Louis, Lawrence and Western Railroad. The life of the railroad (and Sigel Station) was short. It was established in 1874 and was defunct by 1877. Lynn Nelson, professor in the history department at the University of Kansas, wrote about a specific community event in Sigel: a community oyster stew supper. Given that many Douglas County settlers were from New England, they enjoyed having oysters as part of their diet. Nelson described the Sigel festivities as follows:

A week or so before Christmas, the men and boys of the community would gather together just before dawn and would be divided into two teams, each with an assigned territory. The two groups would hunt rabbits from first light, with the children periodically bringing the kill to the Sigel store, where the wives and daughters of each team would skin and gut the rabbits, and stack them in a safe place outside so they could freeze. The hunt was over at sundown, and the last members of each team had brought in their last kills by that time. The women would have made hot coffee and donuts, and everyone would sit, warm themselves, and talk about the day’s adventures while two impartial judges counted up each team’s total. The team who had brought in the fewer rabbits were announced as the ones to arrange the oyster feed. The rabbits and their pelts were taken into Topeka by wagon and sold to the butchers, furriers, and shippers there. The money from the pelts was placed in a local bank to be used for charitable purposes in the community, and the men of Sigel received a note of credit for the rabbit carcasses they had brought in. They immediately used their note of credit to order as many hogsheads of oysters they could afford.

There was an ample supply of oysters on the East Coast. When packed in brine, the oysters could survive long enough to be shipped to Kansas in an unheated rail car. The losers supplied milk, cream and butter. They brought washing “cauldrons” to the schoolhouse to prepare for the community gathering. The wives and daughters baked bread the day before so it would be fresh for the dinner. Because the oysters were cooked outside, a long plank was placed on an incline in one of the schoolhouse windows. The losers slid the wash basins of stew down the plank, and they began to serve the stew to the winners and their families. For dessert, there was fresh coffee and mince pie made from meat, fruit, suet and brandy.

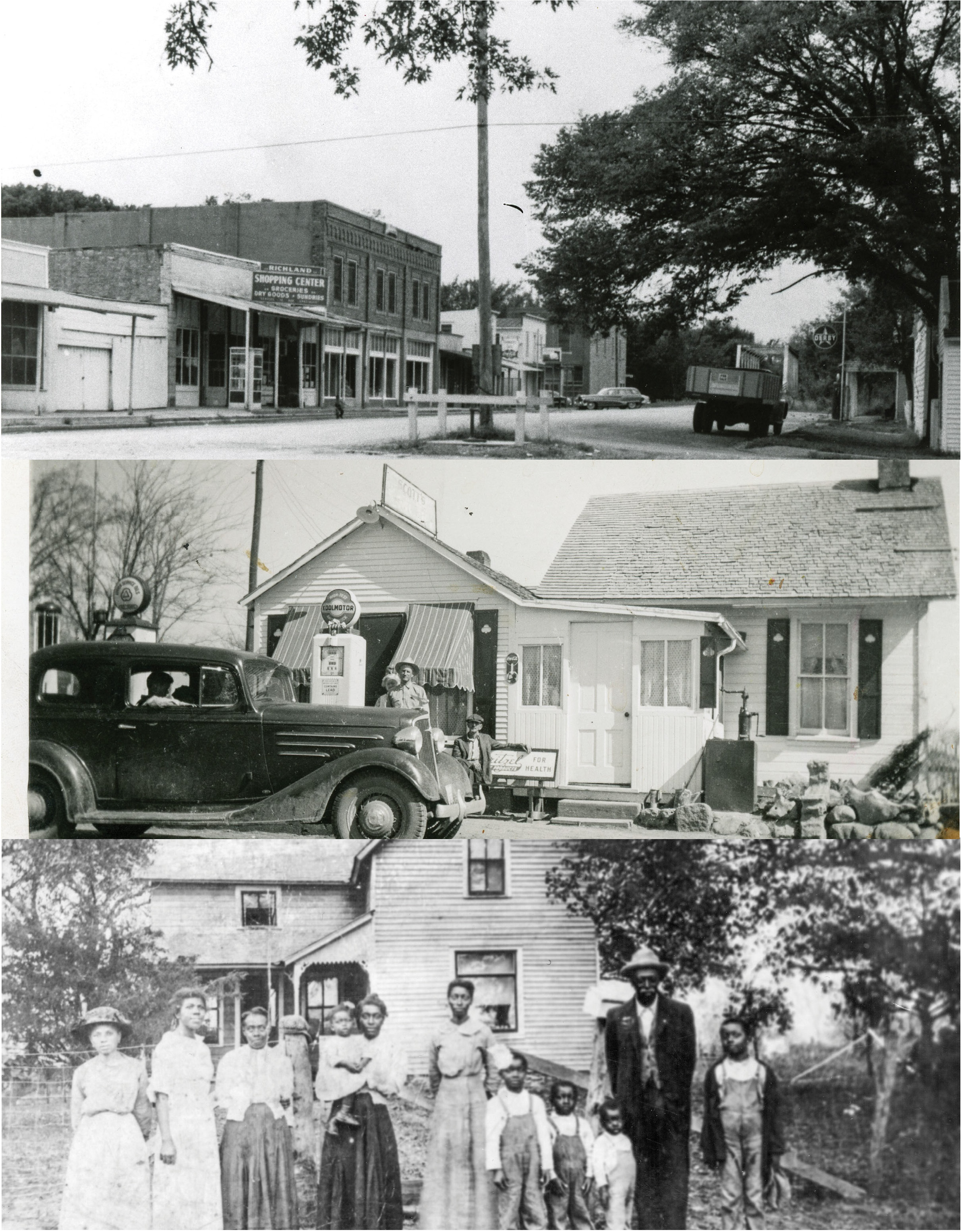

Old Belvoir School Courtesy Wakarusa River Valley Heritage Museum

All of these communities had rural school districts named for them. The first for Belvoir was School District No. 26. It was replaced by Belvoir District No. 84. When it was first established, classes were held in a house, and the first teacher was Alice Dension for the term ending in 1874. Bloomington was School District No. 31, and the Sigel district was No. 8.

As the dam was built, the farmers in the area had to sell their land to the government. Martha Parker, a well-known historian of the Clinton area, recalled that her family farm in the Wakarusa Valley was one of many purchased by the federal government in the mid-1960s. They sold 80 acres and their home for $200 an acre, which was worth about $108,000. As the people being displaced began to realize the extent of the land being taken, they became upset and started referring to the project as the “damn dam.” As work on the dam project began, former residents watched houses that were close to a creek or ravine being pushed into them. In other places, the Corps dug holes big enough to be the final resting place for houses and outbuildings. Many felt bitter about the building of Clinton Dam and Lake for years. Martha Parker chose to accept the existence of the lake and to rely on her memories of the area.

While their protests and petitions were unsuccessful, the Corps of Engineers offered a newly formed nonprofit history group a lease to 3 acres where the J. C. Steele home had stood. The size of the museum property grew to a total of 7 acres. The nonprofit group organized the Clinton Lake Museum on the site. It now operates as the Wakarusa River Valley Heritage Museum (www.kvha.org), with exhibits and archives documenting the history of the valley and its residents.

The Clinton Lake project solved the recurrent flooding in the Wakarusa Valley. Clinton Lake is the source of water for more than 100,000 people in northeastern Kansas, making it the most relied on reservoir in the state. It also serves as a popular recreational area, with four parks managed by the Army Corps of Engineers and one park managed by the City of Lawrence. The lake offers opportunities for boating, fishing and other water sports. The surrounding land allows access to mountain biking trails, camping, hiking, horseback riding, geocaching, hunting, picnicking and wildlife viewing. These recreational activities have become an important part of the economy of both Lawrence and Douglas County.

I REMEMBER.

by Janet Faust

I remember the first day I walked into the Wakarusa River Valley Heritage Museum. It was March 13, 2018. By this time the museum had already been operating for over 30 years but I wasn’t around during that time. I grew up in the Twin Mound farm community just a few miles outside of Richland. But while Richland and other Wakarusa River Valley communities met their fate from the construction of Clinton Dam and Reservoir, I was away at college and then I married and lived elsewhere.

I REMEMBER THAT.

While growing up, I always heard talk that someday a dam would be built to prevent the occasional floods caused from swelling Wakarusa River banks in rainy seasons. I just didn’t pay much heed to it. As young kids, we kind of looked forward to the Richland floods. The family would pile into Dad’s pickup and he drove us to the edge of town. We would survey how deep and how far the water was out of its banks. Dad would comment on what it might mean to the crops in the low areas and we (the kids) would wade and play in the muddy waters.

Building the dam was just something to talk about. Surely it wouldn’t happen in my lifetime. But, then it did. On occasional visits home, my Mother talked about Martha Parker, about attending meetings, sharing updates and ultimately Martha’s passion to save and preserve local history as generational farms were purchased by the government then demolished.

I REMEMBER WHEN.

Nothing could prepare me for how I felt emotionally when I drove through Richland the last time. This little town had been an economic and social hub for rural families in the Wakarusa Valley. Now vacant buildings sat, boarded up. There were no vehicles, no people, no dogs. Just a shell of a ghost town. Then almost as quickly it became nothing; nothing at all. It was as if the town never existed.

As fate happens, life brought me back “home” a few years ago. Just as quickly, fate brought me to the museum. I was energized to ensure history, especially my community’s history, is saved and shared. What surprised me though, when I walked through the museum doors for the first time, was how much local history was already packed into such a small space. The museum is a well-kept gem on the banks of Clinton Lake but the walls are bursting to tell more stories.

Over the past two years, the museum’s board has worked on meeting, interviewing and gathering more local memories from those who felt the impact of Clinton Dam the most. As time marches on way too quickly, the window to capture first person recollections has narrowed. And those interviews have uncovered many more photos and artifacts that brought us to the realization that we must grow the museum’s physical space to do justice to the memories.

I REMEMBER WHY.

That is why a building expansion capital project is being launched. I’m honored to be a part of a museum board that has the vision to “honor our past and build our future.” In the meantime, we are clearing the main exhibit hall of other displays to make way for one of the largest community exhibits the museum has ever tackled. When we open the “Remember Richland” feature exhibit this summer, visitors will be able to step back in time to the earliest days when Richland was established to the town that many will remember through the 60s.

I look forward to remembering it with you.

![]()