| story by | |

| photos by | Steven Hertzog |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

Throughout the county, unincorporated areas have thriving businesses.

Vineland

Kathy and Jack Wilson are facing a bit of a dilemma.

The owners of Washington Creek Lavender, south of Lawrence in Lone Star Township, had a spectacular crop in 2020. Just spectacular. But COVID-19 kept everyone home in 2020, including workers. So Kathy had to weedwhack the fields twice by herself.

This year, however, the 6,000 violet lavender plants lining the acres of the Wilson’s hilltop farm have turned the dark grey of an approaching thunderstorm. Remember that week in February when there was a 70-degree swing in temperatures? The lavender plants didn’t handle it well. Several years ago the same thing happened, and the plants recovered. This year, Wilson says, “Who knows?

“When we make a mistake, we don’t make the same mistake twice,” he continues, pausing for the punchline. “We make it seven or eight times.”

Washington Creek Lavender is but one satellite business orbiting Lawrence in Douglas County. BlueJacket Crossing Vineyard and Winery, near Eudora, and McFarlane Aviation and Vinland Valley Nursery, near Baldwin City, are among many others.

These sorts of mom-and-pop businesses are the lifeblood of many rural and exurban communities in Kansas, says Erik Sartorius, executive director at the League of Kansas Municipalities.

“Whether in cities or counties, these businesses survive because they offer a service or product that is unique to Kansas,” he explains. “Small businesses support our communities through their efforts to provide employment, support the sales tax base and provide unique retail opportunities that showcase Kansas-made products.”

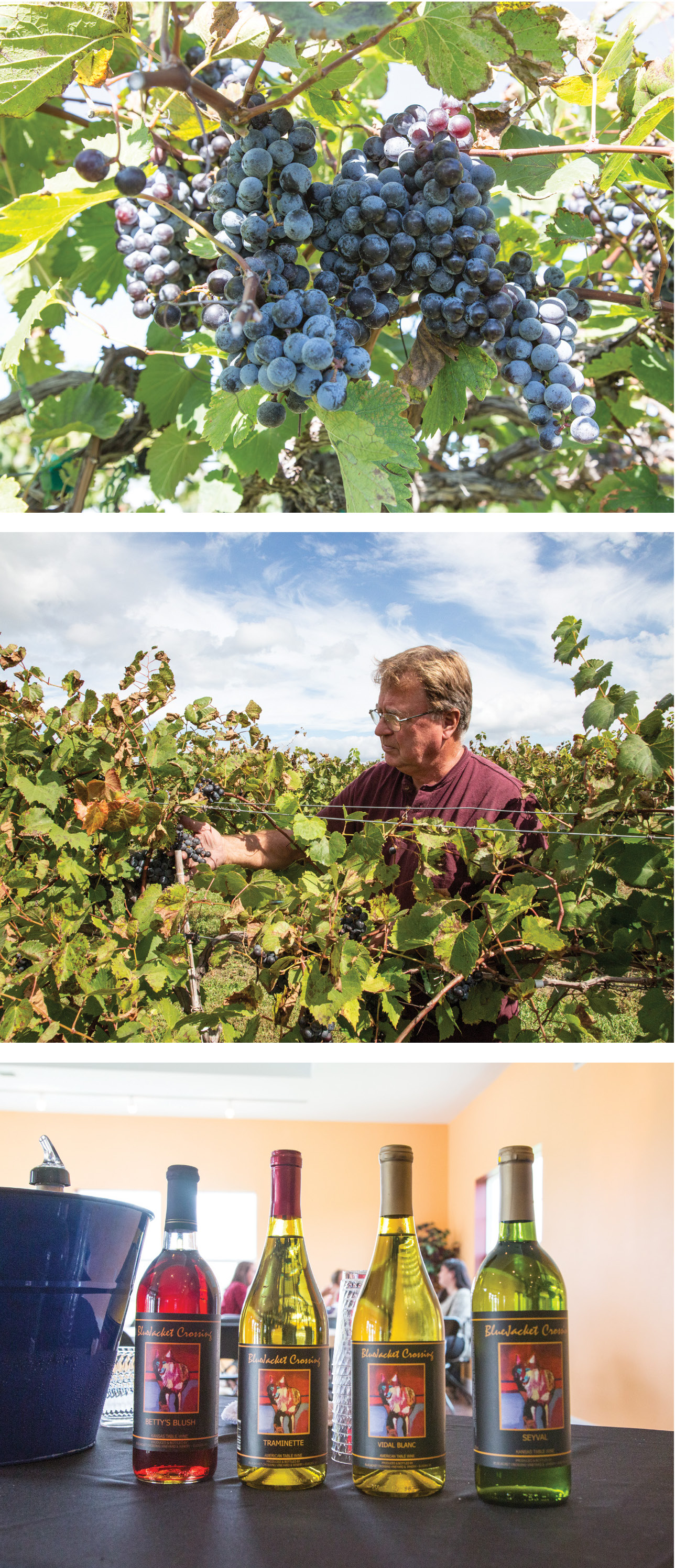

Pep Selvan and the grape vineyards and bottle wine of Blue Jacket Crossing Winery

It’s No Hobby

Pep Selvan, owner of BlueJacket Crossing Winery, says about 75 percent of their customers each weekend say it’s their first visit.

“We focus on products that continue to grow and do well for us,” he adds. “Our red is the best in the state. Our white, same thing.”

Before he began winemaking, Selvan owned a design-build company out west. He moved back to care for a relative, but all that time spent out in wine country inspired him to try his hand at a bona fide Kansas winery.

It hasn’t always been an easy go.

“It’s hard to find labor,” he explains. “The work is tedious. It’s a repetitious job that isn’t exciting enough for young people. And we’ve lost employees because they had immigration concerns.”

The ebb and flow of state and city government, depending on which party has the majority, also makes life complicated.

“I’m 75,” Selvan says. “I’m not in the mood to deal with them sometimes.”

This isn’t just some hobby farm. BlueJacket is trying to maintain a grape standard and create a wine that can compete alongside any other. “Some wineries just have some grapes but slap a label on wine they bring in, then they have live music and slushy trucks and what have you,” he says. “We’re a boutique winery, producing about 10,000 gallons of wine.”

Selvan says neighbors have been mostly supportive over the years, though it didn’t start out that way.

“I think in the beginning, we were a pain in the neck to our neighbors,” he explains. “Grapes are very sensitive. And sometimes crop overspraying—nothing malicious or anything—can be a problem. And that’s true for tomatoes, grapes, a lot of things.”

At the end of the day, they’re not only creating thousands of gallons of high-quality wine, they’re also running a registered agritourism spot in Kansas.

“We have to feel good about the quality of the product,” Selvan says. “We’re doing all we can manage right now.”

Entrance to Vinland Nursery; A Lawrence customer enjoying her first visit to Vinland Nursery; Owners Amy Albright and Doug Davison; One of the many buildings that encompass the Nursery

Organic Practices a Draw

Amy Albright, who co-owns Vinland Valley Nursery, south of Lawrence and north of Baldwin, says one of her biggest obstacles is the perception that the drive to Vinland is lengthy. (It’s barely 10 minutes, less time than it takes to drive from the Kansas River bridge to Target.)

“Until someone drives out here, they think it’s out in the sticks,” Albright says. “It’s really not.”

Once people make it to the farm and nursery, chances are they’ll return. Most customers are from Lawrence, but people come from everywhere.

“We get a lot of people from Topeka and Kansas City,” she explains. “I don’t know if the folks from Iowa have been down here for a couple of years, but we had people who would drive trailers down in the spring to come here and shop, and drive the long distance home. So that was kind of cool.”

The draw? Native plants and organic practices that are rare at many other greenhouses.

“That’s kind of our thing,” Albright says. “I think the native plant-growing and the organic growing practices bring people back.”

Right out of college, she was a wildlife rehabilitator, where she learned what damage pesticides can do to the native flora and fauna. When first starting the farm, they didn’t carry pesticides to resell in their shop, which was strange to some folks. People expected to pop in and get Malathion or whatever was popular at the time.

Grass seed, Albright says, once had about 40 percent clover mixed in. Then the lawn-care industry convinced the whole country to spray something on everything.

“It has not been easy,” she explains. “The interesting thing is how much that’s changed over time. Because now people’s expectations are just completely different, and their sensibilities about using (chemicals) have shifted monumentally.”

Albright says she feels “creepy” saying so, but COVID actually has been good for them businesswise.

“People wanted to be in their gardens,” she continues. “It was just a safe activity for them when they had nothing else to do.”

Co-owner Doug Davison, who has built and rebuilt nearly every building on the farm, says as soon as the weather allowed last year, he, Albright and other staff pushed every plant they could outside so people could walk around and browse at safe distances.

Part of the draw was that the nursery is an outdoor space. Staff enforced mask-wearing inside the greenhouse and the barn. All in all, though, an influx of people made for a fairly successful 2020.

“Thank God we weren’t in the restaurant business,” Albright says. “Yikes.”

McFarlane Aviation in Vinland

From Kansas to the World

Just down the way from Vinland Valley Farms is McFarlane Aviation, an airplane parts manufacturer that serves people and planes all over the planet.

They’ve worked on the Fujifilm blimp. They replace parts on aircraft from the 1920s and ’30s. They worked on the plane that reenacted the D-Day invasion in Normandy. All just north of little ol’ Baldwin City, Kansas.

“About 30 percent of our customer base is overseas,” says CEO David McFarlane. “We pride ourselves on customer service. We respond to everyone as quickly as we can. We make a better product that lasts longer and costs less. That’s it.”

If it was that easy, though, everyone would be doing it. McFarlane’s leg up is his lifelong fascination with aviation.

“It’s interesting to see things they did in the ’20s and ’30s that still work,” he says. “Some didn’t. It gives you a lot in the way of education.”

McFarlane bought the airport north of Baldwin in 1978, where they repaired planes, made parts and provided aerial services.

Upset with the quality of airplane parts in the late 1980s, the company decided to start making the parts. And they make it all, whether it’s for turbo props or business jets.

“We build unique things for unique people,” he adds.

It may sound unique to have a worldwide aviation manufacturer in the middle of the United States, but McFarlane believes it makes perfect sense.

From Kansas, the company can ship to the East Coast or the West Coast quickly. And the rural environment has become a big draw for employees.

“It used to be people were moving out of rural areas to the city,” he says. “Now they’re moving out of the city into rural areas.”

Jack and Kathy Wilson in their Washington Creek gift shop

Choosing Rural

The Wilsons at Washington Creek Lavender are a perfect example. They moved from Chicago to rural Douglas County, where they tried a couple of other ideas before they settled on Washington Creek Lavender.

They tried tomatoes, but a hailstorm wiped them out. Next up was organic basil. The crop was great, the payout not so much. Then the couple considered a winery.

“With wine, if you want to make a little money, you have to spend a lot of money,” Wilson says.

The couple landed on lavender in 2006 because of its versatility. They started with about 10 plants just to see if it would work. Now they have acres. And they get by with a lot of help from their friends.

“I’m from the Jersey shore, and people help, but nothing like around here,” he continues. “The way people help one another, it’s nothing I’ve experienced before.”

Most years, Washington Creek Lavender makes more than 40 different products: dryer sheets, neck comforters, closet hangers, coasters, cup holders, bandannas for dogs and much more.

Normally, the shop is filled with pesticide-free lavender varieties: Gros Bleu, French Fields, Royal Purple, Buena Vista—the list continues. It hangs and dries on racks until it is ready to be separated from the plant with a thresher that’s a little bigger than a typewriter.

The lavender is then distilled into essential oil. The Wilsons sell it all over, as well as locally at Lawrence restaurants, which use it in drinks, syrups, muffins and various other consumables.

On a recent visit to Washington Creek, the solar-powered drying barn and shop stood mostly empty as the lavender plants recovered in the fields. Workers cleared weeds and grass around the plants, and clipped away bad parts all while dodging snakes and other critters.

Wilson estimates the crop is two or three weeks late, which he hears over and over from other people in the area who garden and farm. Hope sprouts eternal, however. Here and there, shoots of green pop up in the middle of the grey plants, sparking great joy in the Wilsons.

“You have to have passion,” Wilson explains. “You have to have help, and we have great help. And you have to enjoy what you do. And we really do. We really do.”

Vineland

![]()