| story by | |

| photos from | Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas |

| OPEN A PDF OF THE ARTICLE |

Though not modern like many of the athletic venues across the country, its intimate atmosphere and historic qualities are what make Allen Fieldhouse special.

Though not modern like many of the athletic venues across the country, its intimate atmosphere and historic qualities are what make Allen Fieldhouse special.

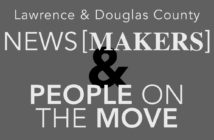

Phog Allen inside the Allen Fieldhouse

As a junior at Salina Central High School, Richard Konzem wasn’t unlike most other wide-eyed farm kids growing up in central Kansas. He was unsure of what the future held beyond high school. He wanted to go to college but had yet to give any real thought as to where.

A trip to a state basketball tournament in March 1975 changed all that.

As the van carrying the Central boys basketball team turned right off of Iowa Street and headed down the hill on 15th, Konzem, the team’s manager, had his gaze immediately drawn to the huge expanse of limestone and brick to his right, just west of James Naismith Drive. It was the most majestic fortress young Konzem had ever seen to that point. And once inside, the rays of light shining through the upper windows, illuminating the basketball court below, the new Tartan-surfaced track surrounding the court, expansive rafters, clouded glass office doors with images of Jayhawks painted on them: It was all magnificent.

“I decided right then I was coming to (the University of Kansas),” Konzem says.

Salina Central went on to win the state boys basketball championship that weekend. But Allen Fieldhouse already had claimed yet another devotee, just as it has on the hundreds of thousands who have walked through its doors before and since.

“Being a farm kid from Kansas … the limestone exterior and size of Allen Fieldhouse was awe-inspiring,” says Konzem, who went on to spend more than a few years working in the building as manager of KU’s men’s track and field program, as a director for the University’s Williams Education Fund and as an assistant athletic director. “And they had the thing you don’t see in many arenas: the windows.”

The most cherished quality of Allen Fieldhouse, one the old barn has worked hard to attain over its nearly 66 years, is its history.

The Allen Fieldhouse surrounded by a field before the campus grew up around it.

KU’s Front Porch

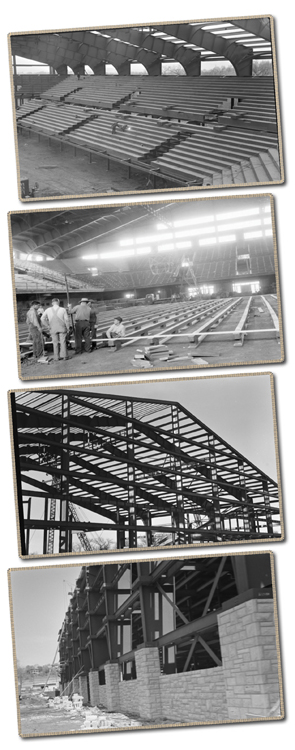

Construction of Allen Fieldhouse

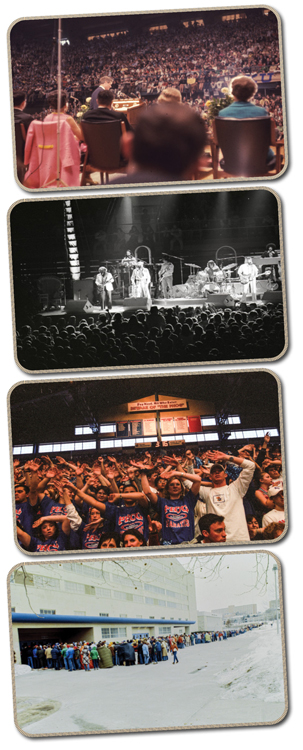

The Fieldhouse, labeled as such because its floor originally consisted of clay and dirt, has hosted a vast array of events and luminaries over the decades. Sen. Robert Kennedy spoke before a house-record crowd of 20,000 there in 1968, months before his assassination. World-famous entertainers have performed there, from Harry Belefonte—who performed the first concert in Allen in November 1964—to Louis Armstrong, Ike and Tina Turner, Elton John, the Beach Boys and comedian Bob Hope. In 2004, President Bill Clinton spoke alongside former Kansas Sen. Robert Dole.

The Fieldhouse hosted KU commencements when bad weather forced participants away from Memorial Stadium and indoors. It hosted enrollment in the fall when students still pulled cards for classes. Two indoor track world records were set in the building. Volleyball, wrestling, even crew teams practiced there.

All of the greatest athletes in KU’s rich history—Wilt Chamberlain, Gale Sayers, Jim Ryun, Lynette Woodard—practiced or competed in the building that is commonly referred to as “the house that Wilt built.”

Allen Fieldhouse has been everything to everyone.

“Allen Fieldhouse is considered the front porch of the University,” says John Novotny, who was associated with the university from 1966 through 1981 as an academic counselor, assistant athletic director and first Williams Education Fund director.

Of course, there’s what Allen Fieldhouse is mostly known for: the home of Jayhawks basketball.

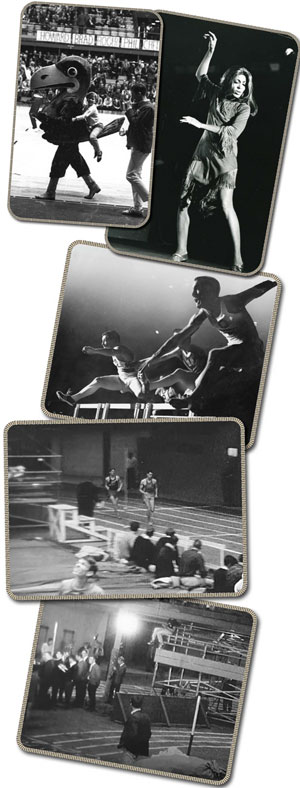

A young fan rides the tail of Big Jay, Tina Turner performing in The Fieldhouse and Indoor track meets

There are all of those great teams, players and coaches (six of the eight who have coached the Jayhawks did so in the fieldhouse) who have mostly won there, including 33 conference championships (and a national-record 14 straight during the Bill Self era), a 69-game home-court winning streak (not to mention two other separate streaks of 62 and 55 games) and two teams that won NCAA national championships—in 1988 and 2008. All the great games against Big Eight and Big 12 conference rivals and national powers, the most memorable of which just might be a 150-95 victory over Kentucky in 1989. And perhaps the most cherished moment in the building’s 66 years, the return of Chamberlain to the Jayhawk fold and the halftime ceremony and speech that left no dry eyes in the house.

The Jayhawk men sold out 306 consecutive games dating back to 2001, a streak only a worldwide coronavirus pandemic could interrupt. In 2014, the Guinness Book of World Records verified Allen Fieldhouse as the loudest indoor arena.

Former Duke player and longtime ESPN basketball analyst Jay Bilas called Allen Fieldhouse the “St. Andrews of college basketball.”

“I think it’s the best sports venue in major sports, not just college basketball,” says Blair Kerkhoff, sportswriter for The Kansas City Star, who has covered college sports since 1989 and covered Jayhawks basketball from ’89 to ’97. “It’s as intimate as a 16,000-seat building can be, and the five minutes before a game—historical video, player introductions—isn’t duplicated anywhere.”

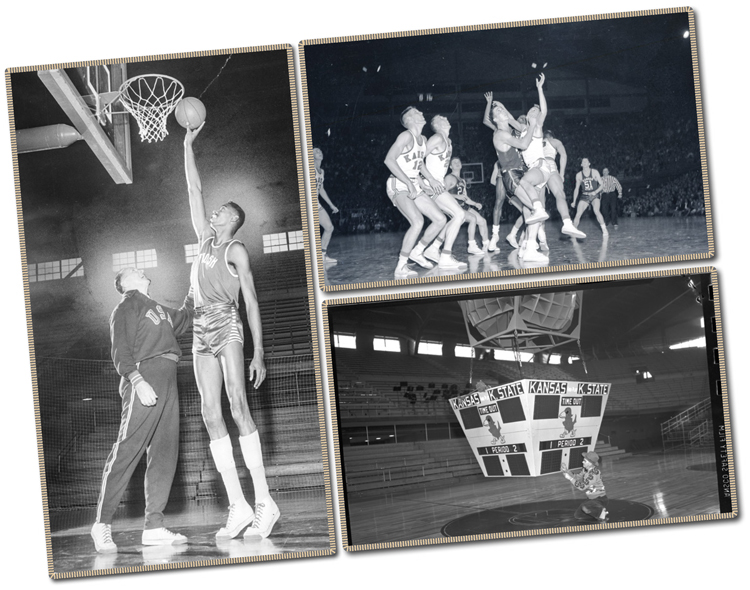

Wilt Chamberlain and coach Phog Allen; First game in the Allen Fieldhouse against KSU 01-03-1955; Installing the new scoreboard;

A Rich History

The history of Kansas Jayhawks basketball is inextricably tied to the history of the game itself. The Jayhawks played their first season in 1898-99, and their first head coach was none other than the inventor of the game itself, Dr. James Naismith. They originally played in the basement of old Snow Hall, with a 14-foot-high ceiling, before moving into old Robinson Gymnasium in the early 20th century. In 1927, the team moved to Hoch Auditorium, with a capacity of 3,800, for the next 28 years.

It was during this time that the Kansas basketball program was turned over to a Naismith disciple, Dr. Forrest C. “Phog” Allen. Allen would go on to coach the Jayhawks for 39 seasons and establish himself as “the Father of Basketball Coaching” for his innovations to the modern game.

A key moment in Allen’s coaching career came in 1948, when Kansas State constructed an 11,000-seat fieldhouse known as Ahearn Field House. Allen had brought up a new basketball arena to the University of Kansas and state in 1927, but the Great Depression and World War II quickly curtailed those plans. The construction of Ahearn reignited Allen’s desire for KU to have one of the largest basketball venues in the Midwest, if not the U.S. In 1949, a bill was renewed that appropriated $750,000 in state funding for the project, estimated to cost $2.5 million.

The actual cost was between $2.6 and $3 million. The Fieldhouse was constructed with 700,000 bricks and 2,700 tons of structural steel that was secondhand from Chicago and used during the Korean War. The University had to agree to include the word “armory” in its original plans so that it could procure the steel during wartime.

“We’d never built anything this big,” Warren Corman, one of the original architects on the project, said last year on an episode of The Jayhawker Podcast. “The structure itself was the most important thing, because it had to be built to last forever. And it had to span 200 feet, because the floor itself was 50 feet.”

Corman said one of his key responsibilities on the job was to count weekly to ensure there were 17,000 seats that would fit into the fieldhouse.

“I remember it as a heated big barn,” he says. “I had no idea it would be so iconic.”

The year 1954 was one where the Father of Basketball Coaching suffered a rare loss of an argument. It came down to Allen and Naismith as to whose name would adorn the Fieldhouse. Allen wanted his mentor to have the honor, but it was put to a vote among KU students, and Allen came out on top. As a consolation, Michigan Street, which ran along the east side of the Fieldhouse, was renamed Naismith Drive.

On March 1, 1955, the Jayhawks men’s basketball team defeated archrival Kansas State 77 to 67 in the dedication game for Allen Fieldhouse in front of an overflow throng of 17,228, to this day the attendance record for a game there. They played on a maple wood floor screwed into supports planted in the clay floor.

Something for Everyone

Throughout its first three decades, Allen Fieldhouse was used by student-athletes from just about every sport KU sponsored.

“In the old days, they took the basketball court out in the off-season,” Novotny says. “People forget how big track was back then. Basketball hadn’t gotten as big as it got when Larry Brown came [in 1983]and then was followed by Roy Williams and Bill Self.”

Fieldhouse architect Corman recalls, “I can remember the women’s rowing team up in the concourse practicing. There was athletic stuff happening all over the building.”

“I remember the football team practiced for the ’81 Hall of Fame Bowl crosswise on the basketball court,” Konzem says. “At the same time, the baseball team practiced in the upper corner in batting cages.”

But basketball was king, and as the sport grew in popularity and financial impact, so did the Fieldhouse and its atmosphere, which over the years added championship and individual banners throughout the rafters and, in 1988, a long banner hung high up in the north rafters that read: Pay Heed to All Who Enter—Beware of the Phog.

“It was such a historic place, and I wanted to coach in Allen Fieldhouse,” says Roy Williams, head men’s basketball coach at North Carolina, who coached the Jayhawks to four NCAA Final Fours from 1988 to 2003. “After the first two seasons there, I became even more convinced we should always play there. It was the greatest home court advantage I’ve ever seen.”

Preserving History, Evolving the Future

Former KU athletic director Lew Perkins wrote in the introduction to the 2004 book Beware of the Phog: 50 Years of Allen Fieldhouse, “We must be diligent in making sure (the Fieldhouse) remains highly functional. But we will not do so at the expense of tradition and history.”

Robert Kennedy speaks in The Fieldhouse; The Beach Boys perform; Students Waving the Wheat; Students line up in the cold to get tickets for a KU Basketball game

Indeed, many of the renovations and upgrades the old barn has undergone over the years have been made with enhancing the history and tradition in mind.

Back in the old clay/dirt days, the Fieldhouse surface had to be watered and dragged daily to settle dust and provide an even running surface for track athletes.

“A custodian watered the dirt each morning,” Novotny says. “There was a group of faculty who liked to run at 6 a.m., and I remember them meeting with the chancellor about the water.”

A Tartan surface covered the dirt in 1974, and in 1979, a new maple wooden basketball court was installed. Eventually, other sports like track and field and volleyball got their own indoor facilities: Anschutz Sports Pavilion opened in 1984 for indoor football practice and indoor track; Horejsi Family Athletics Center opened in 1998 for volleyball and basketball practice, leaving Allen Fieldhouse to be modernized as one of the country’s preeminent college basketball arenas.

Lighting and sound systems and scoreboards have been consistently updated and upgraded over the years. In January 2006, the Booth Family Hall of Athletics was added to the east side of Allen, creating a dazzling display of the university’s athletics history. In lieu of not having private suites, up to four different donor spaces were created that can accommodate about 600.

In April 2016, the DeBruce Center opened, highlighted by the original copy of Naismith’s original rules of “basket ball.” The history of the game had come home.

“Allen Fieldhouse is known for its historical significance first and foremost,” says Brad Nachtigal, associate athletic director, operations and capital projects, who in his 21 years with KU has witnessed three major Fieldhouse renovations along with other smaller projects. “The building has its original interior. It’s stood the test of time.

“We’re definitely always looking for ways to make fan amenities better. We continually strive to preserve and modernize what we can.”

In the end, many agree that the qualities that make Allen Fieldhouse not modern are what make it the special place it is.

“I’ve been to a lot of fancier places, but there’s something about this place that makes it feel like being home,” said Corman on the Jayhawker Podcast. “Even though it’s big, it’s intimate with people being seated really close together, not much knee room.

“I don’t think they’ll ever take it down.”

![]()