Creating a Business on the Basis of Sustainability

| 2020 Q1 | story by Emily Mulligan | photos by Steven Hertzog

L: Faculty – Prof. Bala Subramaniam, Prof. James Blakemore, and Prof. Kevin Leonard; PhD Students-David Sconyers and Matt Stalcup investigate how to convert carbon dioxide (a greenhouse gas and environmental polutant) into useful products using renewable electricity. R: Graduate student, Vyoma Maroo uses a gas chromatograph instrument to determine the effectiveness of producing new derivatives from corn ethanol in their research project funded by the Kansas Corn Commission

KU CEBC

The chemicals of the future will be plant-based and biodegradable, and require less of an environmental footprint to produce. They will have to have all of these attributes, because the Earth’s natural resources are depleting daily.

Industry and cutting-edge scientific research are collaborating at the University of Kansas to create the future of materials, such as current-day plastics. The Center for Environmentally Beneficial Catalysis (CEBC), on KU’s West Campus, is home to these unique collaborations, overseen by director and distinguished professor Bala Subramaniam.

“Imagine the day when the crude oil runs out. It will be a rude awakening. We have to start now to create what will replace it,” Subramaniam says.

The CEBC has been developing new chemical technologies for research and industry since its founding in 2003. With National Science Foundation (NSF) funds in the millions for many of its projects and guidance from the 10 companies on its board, the CEBC is demonstrating chemical technologies at the laboratory level. By pairing academic researchers with industry partners and using the NSF funding, the product and process development are financially sustainable, as well as environmentally.

Two of the many recent laboratory successes that Subramaniam says have shown promise to replace plastics are products made using the plant component lignin and products made by electrochemically reducing carbon dioxide to carbon monoxide.

Lignin is a component in the cell walls of plants that makes them rigid and woody. CEBC researchers extracted lignin from agricultural leftovers (corn stover and wheat straw) and discovered a simple method to produce vanillin, a component of vanilla bean extract. They then developed a process to turn the synthetic vanillin into a renewable resin with potential use in building materials. The CEBC is working on this technology alongside corporate farming giant ADM, which has a lab at KU’s Bioscience & Technology Business Center (BTBC), also on West Campus.

CEBC chemical engineers and chemists have demonstrated a novel way to convert carbon dioxide, a gas emitted during fossil fuel combustion, to something useful. Their technology uses pressurized carbon dioxide and electrical energy to transform carbon dioxide to carbon monoxide, which can be combined with other reactants to make products.

Both of these processes could be part of Subramaniam’s vision of the future “bioeconomy”—likely 40 to 50 years from now. In the bioeconomy, the chemicals will need to be produced close to where the sources are harvested.

“Instead of now, where chemicals are produced at a single giant refinery, you’ll have agricultural regions where we will use the land to make everyday plant-based chemicals and ship them from there,” he says.

Stacy Schmidt with her children at Narrow Trail Farm, photo by Brian with Siorai Images

Narrow Trail Farm

Stacy Schmidt is possibly Douglas County’s answer to Estée Lauder with a couple of slight exceptions. For one, the sources for her cosmetics are extremely local, from her family’s land at Narrow Trail Farm, in Baldwin City. For another, sustainable practices reach all the way from in the ground up to the sky at the organic diversified farm; and those practices extend to the ingredients and packaging for the farm’s handcrafted products.

Narrow Trail Farm, 1564 N. 450th Rd., Baldwin City, grows hay, vegetables, berries and cut flowers, and also harvests chicken eggs, duck eggs and honey from its beehives. Schmidt uses beeswax and honey as bases for most of her skin-care products and incorporates flowers and other ingredients from the farm as she sees fit.

Schmidt sells her skin-care products at Essential Goods, in Lawrence, The Nook bookstore, in Baldwin City, and online. She offers lotion bars, lip balms, body butter, soap, lip tints and colorful mineral makeup, all of which she mixes up at the farm and packages in materials like bamboo and recycled paper. A cell biology major, she started making the mostly preservative-free products when she realized that half of her freezer was full of beeswax. She has plans to add an eye makeup cream product and an all-over face stick for lips, cheeks and eyes.

“My family are my guinea pigs. There is no animal testing; we do human testing,” she jokes.

The farm’s sustainability begins in the ground, where Schmidt and her husband, Jeff, compost horse manure and chicken manure into compost to use as fertilizer. They also have hugelkultur beds, which are pits in the ground that use dead tree limbs and branches from the farm as a base and, when combined with compost, require no irrigation or fertilization.

On the ground, the vegetables and flowers are grown in raised beds for no-till and low-irrigation maintenance.

Above the ground, the farm has 11 beehives that produce honey and beeswax, and of course add to the local bee population to help ensure pollination at the farm and for miles around.

Up in the sky, the Schmidt’s house sports a 7½-kilowatt solar array, making it a net-zero energy home. Soon, they will add solar panels that run on a battery off the grid to power their greenhouse. The sky also provides the bulk of the irrigation to the farm’s crops in the form of rainwater that they capture in a giant tank. They hope to add another tank soon to capture even more.

“All of the sustainability grew out of how we live our life. We’ve just scaled it up to support the farm,” Schmidt says.

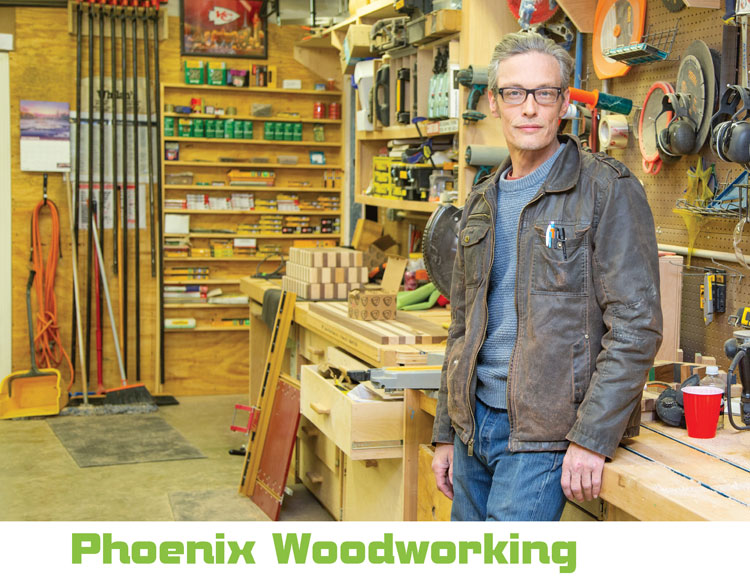

Shine Adams, owner of Phoenix Woodworking and a certified peer counselor, inside his workshop

Phoenix Woodworking

Phoenix Woodworking is moving to a much larger shop this year, which will allow for more products. Much more importantly, though, the larger shop should allow for hiring more employees, because that is really what Phoenix is all about.

Shine Adams, a certified peer counselor, founded the company with the goal of teaching “unemployable” people a skill, so they might have a chance at permanent employment to set their lives on a different track. Phoenix hires homeless people, those recovering from addiction, people with criminal records—anyone in whom Adams can see the potential and is willing to learn.

“We believe that everyone deserves a chance to work. It’s not a charity; it’s an opportunity,” Adams says.

The company, which was formerly called Sun Cedar, has previously made carved cedar wood air fresheners, enamel pins and refrigerator magnets. In the new space, located at Natural Breeze Remodeling, Adams says he is looking at making bat houses, cutting boards and trivets, among other things that can be crafted from Natural Breeze’s offcuts and scraps. The more products Phoenix can sell, the more employees Adams can hire—and he is hoping to grow his workforce in 2020.

“The great majority of people that Phoenix has hired the past couple years have moved on to better jobs that they have kept. No two stories are the same, but the commonalities are that we strive for them to leave Phoenix better than when they came here,” he says.

Most of Adams’ employees have come to Phoenix without having any positive experiences in a workplace. They don’t understand that a job and coworkers can be enjoyable, he says, let alone that they can learn something. Teaching employees soft skills is what Adams says is most important for him: treating people with respect, showing up on time and relating to authority without animosity, for example. That is where his training as a peer counselor comes in, as he and the employee can focus on how the employee can “win” instead of what the challenges are.

Adams was the face of Phoenix’s large Kickstarter campaign in 2019, which raised more than $40,000 and allowed him to hire three people to fulfill Kickstarter gifts. And, it has put him in the position to expand the catalog of products with future employees.

“I’m not trying to solve the homeless problem one person at a time. I’m doing what I can with what I know. If we can keep more people consistently employed, we’re doing what we set out to do. Ideally, I’m making this work so that other people can see that it works,” he says.

The Mennonite Church has a beautiful colorful concrete floor that incorporates several of PROSOCO’s concrete finishing products in an original commissioned artwork, photo courtesy PROSOCO

PROSOCO and Build SMART

Much of the conversation about greenhouse gas emissions centers around cars and transportation. Actually, in 2018, residential and commercial buildings created 40 percent of greenhouse gases, according to the United States Energy Information Administration. PROSOCO and Build SMART, two innovative local construction materials and building prefabrication companies, are working on the front line to reduce buildings’ emissions and to make sustainable buildings more possible and more affordable.

PROSOCO and Build SMART, located in East Hills Business Park, are sister companies and subsidiaries of Boyer Industries Corp. Both companies have products that fulfill the ever-evolving definitions of “sustainability” in the construction industry—and in society—for projects across the U.S. and Canada. Anymore, sustainability of buildings is not just about energy efficiency and low waste, although those are high priorities. The coalition of green builders, architects, suppliers and designers known as Green Building Learning Zone has a vision of sustainability that also factors in affordability, the well-being of the building’s occupants and the building’s accessibility and connection to the community as elements of sustainability. The companies embrace those facets of the definition, as well.

PROSOCO, with 105 employees, is a manufacturer whose products include concrete finishes, window and door sealers, and weatherproofing membranes that are both airtight and waterproof. The company began in 1939 producing cleaners for new brick masonry and has continued to produce cleaning and maintenance materials for brick, block and stone restoration, helping allow those buildings to last 150 to 200 years.

PROSOCO’s Consolideck makes concrete floors durable and scratch resistant, which helps them outlast traditional flooring that must be scrapped and replaced. It has zero volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and no emissions. Moisture from outside is the nemesis to longevity of all building structures, not to mention how mold and mildew can affect a building’s occupants. Fast Flash is a fluid-applied material that seals windows and doors at their joints to keep moisture from entering the occupied space or walls. Cat 5 is a roller or spray-applied product for seamless weatherproofing of an exterior surface.

“Your wall is an assembly that has to stand up over time and not rot the wood, insulation or sheetrock. If you start with a product that isn’t built to last, you’re never making something that is environmental,” says Dwayne Fuhlhage, PROSOCO sustainability and environment director.

Build SMART, which has 23 employees, uses PROSOCO products and other quality construction materials sourced nationally to assemble prefabricated interior and exterior building wall panels that form an airtight “building envelope.” The components are meticulously packed, numbered and organized, then shipped to the construction site,

where they are put up as an entire wall at a time, much faster than traditional “stick-by-stick” construction taking place on-site. The Build SMART System can be used for anything from single-family and multifamily residential buildings to low-rise hotels, retail buildings and schools. Besides being airtight and incorporating products built with exacting environmental standards, the Build SMART Systems save contractors a great deal of labor. Projects are completed more quickly, so contractors can do more projects per year, and that is financial sustainability in the form of savings passed on to the consumer or resident.

“Airtightness and moisture management, when done correctly, gives you a building that is much more energy efficient. We have never had a contractor fail to pass the highest standard airtightness test, the ‘blower-door test,’ at the end of a project,” says John Ware, market development director for Build SMART. “The customer wants price, comfort, low risk and speed. In all of those aspects, the Build SMART System is an improvement over the ‘stick-built’ approach.”

Build SMART’s customized prefabrication achieves efficiencies that save both construction time and money. The company works directly with owners, contractors and architects, customizing the products to each project.

Traditionally, Ware says people have looked to building codes to set the standards for construction. But, environmental standards and technologies have changed so quickly that building codes have not kept up.

“The code is a baseline requirement that makes construction legal; it’s not the best value today,” he says.

As they succeed at constructing and maintaining more and more buildings with their products, PROSOCO and Build SMART are helping to redefine and move the needle on what a “sustainable” building means. It isn’t just a building that incorporates energy-efficient, environmentally friendly components with little to zero waste anymore. Now, to be considered “sustainable,” the building must also be affordable and durable, and provide good indoor air quality for its occupants, among other social- and community-minded goals.

Fuhlhage says that is why companies like PROSOCO continue to innovate products and processes to drive the construction industry.

“When you are taking green construction to scale, you have to connect everything together. You are using the highest-performing buildings as your proof of concept,” he says.

Matt Roman, owner of Resurrected Woodworks

Resurrected Woodworks

Incorporating reclaimed wood is a trend in construction and remodeling projects. But, what happens when that wood was never really “claimed” to begin with?

Enter Matt Roman and his network, which rescues cleared or felled trees from construction projects around the area and mills the wood to become furniture, bowls and other fine woodworking. Roman owns Resurrected Woodworks, 620 E. Eighth St., where he designs and builds items from what he calls “forgotten” trees.

Roman is both sustaining the existence of the trees, which otherwise would be burned or turned to mulch, and providing pieces of furniture that can endure for multiple generations.

“A lot of my clients want something to last forever; they want to hand it down,” Roman explains. “They don’t want something from a chain store, made in a factory, what I call ‘disposable furniture.’ ”

Roman, who has been in the construction industry since 2002, mostly as a framer, rescued his first batch of trees about four years ago, when the University of Kansas demolished the Stouffer Place Apartments at 19th and Iowa streets and subsequently cleared the land. He milled and aged the lumber from the sycamore, walnut and hackberry trees—a time-consuming process.

Soon after, arborists with tree companies around town started calling Roman when they were taking down a tree so he could come with his trailer and haul it away. Retrieving the trees started taking up most of his time and keeping him from working in the woodshop.

“Two years ago, I decided I needed to choose to either make more things with the wood or harvest more trees. Now, I get the wood from others who get the trees, and I focus on making things,” he says.

Most of the wood comes from within 50 miles of Lawrence, and all of it comes from within 100 miles, Roman says.

Within his shop, he ensures that he has zero waste from the wood. Castoffs from furniture become wooden spoons, spatulas and cutting boards; sawdust goes into mulch; and oddball scraps feed his wood-burning stove to heat his home. He and his young daughters have begun making jewelry from wood scraps, as well.

Roman designs custom furniture orders, as well as producing his own end table and table designs, among other things, which he says tend toward a mid-century look. The bowls allow him to explore movement and fluidity, he continues, and he never knows how each one will turn out until it is done. He sells his wares at art shows in the area, from Lawrence to St. Louis, and places in between.

Locally, Roman’s work will be featured at Essential Goods for the month of May, with a Final Friday opening April 24.

PrairieFood Workers at the inaugural PraireFood site in Kansas The initial Prairie Food operating plant in Kansas; photos courtesy of PrairieFood

PrairieFood

Rarely is there a way to put waste right back where it came from. In a sense, and after a highly specialized scientific process, that is exactly what PrairieFood does.

The company is in the testing phase of its product, which could revolutionize the sustainability of organic farming—and save a few million tons of waste every year while they’re at it.

PrairieFood’s process converts animal biomass, aka cow manure in this instance, into a soil fertilizer and plant food, while at the same time eliminating the greenhouse gases contained within it.

“PrairieFood is essentially a product created by taking waste biomasses, deconstructing them to a molecular level and reconstructing them into something new,” cofounder and CEO Rob Herrington says.

Eventually, PrairieFood hopes to create its product from up to four different types of biomass for which its conversion process works: cow manure, distillers’ grains such as ethanol, green waste such as grass clippings and even human waste.

For now, the cattle biomass undergoes the conversion process in about a second, and it can take one of two forms: 1) a solid pellet that resembles Grape-Nuts cereal, which is dry and can be spread across the ground, or 2) a liquid with 30 percent carbons that can be sprayed or applied to the ground.

“Both of these forms fit so well into the legacy farming practices. Farmers can use existing farm equipment with the PrairieFood,” Herrington says.

The environmental advantages are more than just reducing and utilizing waste. PrairieFood produces no runoff nitrates or phosphates like most fertilizers and plant foods, and it also doesn’t activate in the sun in a way that produces greenhouse gases. Instead, the nutrients in either the pellets or the liquid are absorbed into the soil over time, and it creates a productive microbiome with a full spectrum of soil nutrients. Herrington says the research so far indicates that organic farmers will be able to grow yields equal to traditional farmers when they use PrairieFood.

The company will place cargo containers at sites that generate biomass—for now, cattle feedlots—and farmers will collect the waste and place it in PrairieFood’s containers. Then, the biomass will be processed in PrairieFood’s plant, and the now-plant food will be transported straight to the growers and producers who will use it, predominantly organic farms.

In the next three years, PrairieFood will be raising about $50 million in capital to build its plant. In the meantime, the conversion process is patented, and the company owns all of its own intellectual property, while it continues to test at its pilot site in Pratt, Kansas.

Lighting fixtures by Sunlite Technologies

Sunlite Technologies

Inside Sunlite Science and Technology’s headquarters, it looks like a perpetually sunny day, which makes the Sunlite name definitely apropos for the lighting company. In addition to the cheery disposition, Sunlite, at 4811 Quail Crest Place, is creating the next generation of LED lighting technology—so advanced that most Lawrence residents can’t even use it yet.

Sunlite’s LED (light-emitting diode) components are manufactured at its subsidiary in China, and its distinct 2-inch-diameter can lights are assembled in Lawrence, which also serves as the headquarters for national distribution. The LEDs that Sunlite uses really have very little to do with most LED lights that are for sale in hardware stores and big-box stores. LEDs available in those stores today use traditional electrical wiring and still have to retrofit into incandescent lighting setups. What we have now is considered a transition to LED lighting; Sunlite makes and sells what comes next.

Traditional recessed can lights are typically about 6 inches in diameter and usually have a central space from which they light a room, such that locations farther from the lights may require a lamp for reading or to see detail. Sunlite’s LEDs are so small there can be many more of them, and often they are laid out in a grid across the whole ceiling, allowing evenly distributed light at every place in the room.

“All the other companies buy from other manufacturers. We are the manufacturer, so we use our own LED technology in our lights,” Sunlite CTO Jeff Chen says.

Sunlite also makes specialty lights, such as its best-selling “green wall lighting,” for interior walls of plants and succulents. The company also has LED pendant lights, available in multiple colors, for a decorative focal point and lights that can change color or be dimmed.

LED technology has many environmental advantages. Although the commercial customers realize the most significant savings, residential customers’ electricity costs are reduced more than six times when they employ Sunlite’s lighting. The LED lights use more efficient DC (direct current) electrical power instead of traditional AC (alternating current), and they are wired using L2 cable, which is the small wiring typically used with home security systems.

“AC power wastes copper and materials in thicker wires. DC not only saves electricity, it also saves material for house wiring,” Chen explains.

Because of the wiring required, Sunlite recommends installing the new LEDs only in new construction or extensive remodeling projects.

Sunlite’s LEDs also don’t put out any noise, such as the “hum” of traditional overhead lights and even today’s LED fixtures.

LEDs from Sunlite are in businesses and corporate headquarters all across the United States and Canada. Apple, Google, Toyota and Allstate Insurance all have Sunlite’s green wall lighting in their corporate headquarters. In Lawrence, Capitol Federal Hall and the new addition to Marvin Hall on KU’s campus are prominent places that have Sunlite’s LEDs.

Sunlite has been in Lawrence since 1997, when Chen moved the company here from Silicon Valley to take advantage of both friendlier industry and the University connections. The company, which employs 10 people to engineer, design, sell and fulfill orders, received a patent in 2018 for its new LED technology. As far as Sunlite is concerned, the future is bright.