Kansas medical doctor was a pioneer in public health, designing the flyswatter to help combat diseases spread by houseflies.

| 2019 Q4 | story by Patricia A. Michaelis, Ph.D., Historical Research & Archival Consulting| photos courtesy of the Kansas State Historical Society, kansasmemory.org

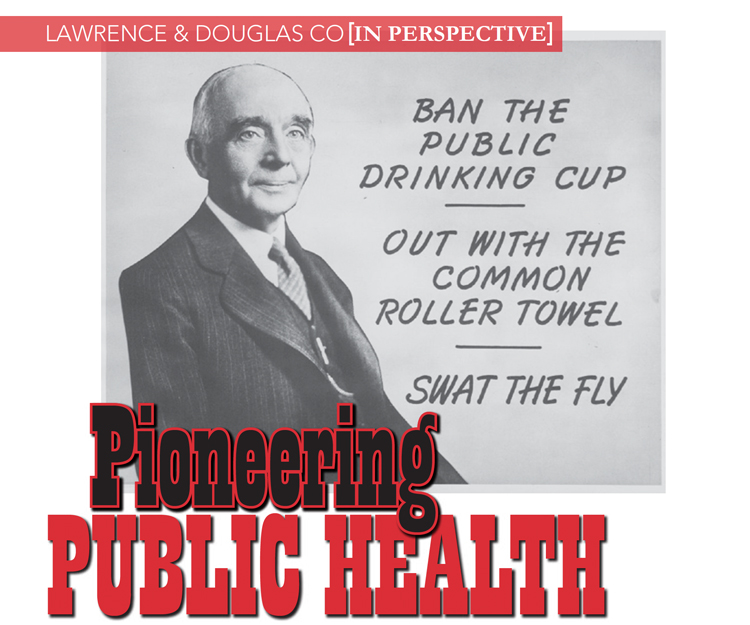

This phrase became the motto of Dr. Samuel Crumbine, of the Kansas State Board of Health, as he campaigned statewide and nationally to improve public health in the early 1900s. Today, we take most of the health precautions he and other public health officials promoted for granted. But that was not the case at the turn of the last century. Crumbine became one of the pioneers in the field of public health in the United States, arguing for the prevention of disease. Lawrence and other Kansas communities benefited from his initiatives.

Doctors were just beginning to understand how germs were transmitted and how everyday practices contributed to their spread. Cities and small towns had dirt streets, and horse-drawn vehicles were the primary mode of transportation. Horse droppings were common on public streets. Windows and doors were unscreened. So flies could move freely in and out of houses and around the community. Towns had public water buckets with a single cup that was used by everyone, and “roller towels” were used to dry hands. Flies also spread germs from the common practice of spitting on sidewalks. These practices were the targets of Dr. Crumbine’s campaigns for better public health.

Samuel Jay Crumbine was born in Emlenton, Pennsylvania, on Sept.17, 1862. His father was a mechanic and served in the 103rd Pennsylvania Infantry during the Civil War. However, he was captured by the confederates and died in Libby Prison before his son was born. Crumbine’s widowed mother raised him on a farm, and he attended public schools. When he was 16, he was employed as a clerk in a drug store in Sugar Grove, where he decided he wanted to become a pharmacist. He moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, and when he was 21, he entered the Cincinnati College of Medicine and Surgery. He graduated as a physician in 1888, but he had moved to Spearville, Kansas, in Ford County, in 1885, where he was one of the owners of a drug store. After receiving his medical degree, he moved to Dodge City, where he built an extensive medical practice with a reputation as a skilled physician. In 1890, he married Katherine Zuercher. They had two children, Warren and Violet.

Kansas Gov. William Stanley appointed Crumbine to the Kansas State Board of Health in 1899. He was named secretary (the equivalent of an agency head) in 1904. He served in that position until 1923. During his tenure, he initiated a number of campaigns to improve the public health of the state. One of his best-known efforts was the “Swat the Fly” campaign. Under his supervision, the State Board of Health released a publication that used graphic language to detail the health issues cause by flies. The following excerpts from a pamphlet published between 1910 and 1915 give a sense of Crumbine’s passion on this issue:

House Fly Catechism

Where is the house fly born?

- In filth, chiefly in horse manure and out-houses.

Where does the fly live?

- Where there is filth.

Is there anything too filthy for the fly to eat?

- No.

Does the fly like clean food too?

- Yes, and it appears to be its delight to wipe its feet on clean food. …

How does he spread disease?

- By carrying infection on his legs and wings, and by “fly specks” after he has been feeding on infectious material.

What diseases may the fly thus carry?

- He may convey typhoid fever, tuberculosis, cholera, dysentery and “summer complaint.”

Did the fly ever kill anyone?

- He killed more American soldiers in the Spanish-American war than the bullets of the Spaniards; and was the direct cause of much of the typhoid fever in Kansas last year. …

How may we successfully fight the fly?

- By destroying or removing his breeding place, the manure pile: making the privy vault fly-proof, and keeping our yard clean; by screening the house; by the use of the wire swatter and sticky fly-paper.

In 1905, Crumbine designed the flyswatter, an adaption of a device on a yard stick called a fly bat.

Another major target of Crumbine’s efforts was to combat the spread of tuberculosis (TB). The disease was a serious problem in the early 1900s because it was a highly variable communicable disease that affects especially the lungs but may spread to other areas (such as the kidney or spinal column). It is characterized by fever, cough and difficulty breathing. It is believed that he became concerned after seeing tuberculosis patients spitting on the floor of a train. Also, he watched a mother give her child a drink from a public drinking cup after it had been used by a TB patient.

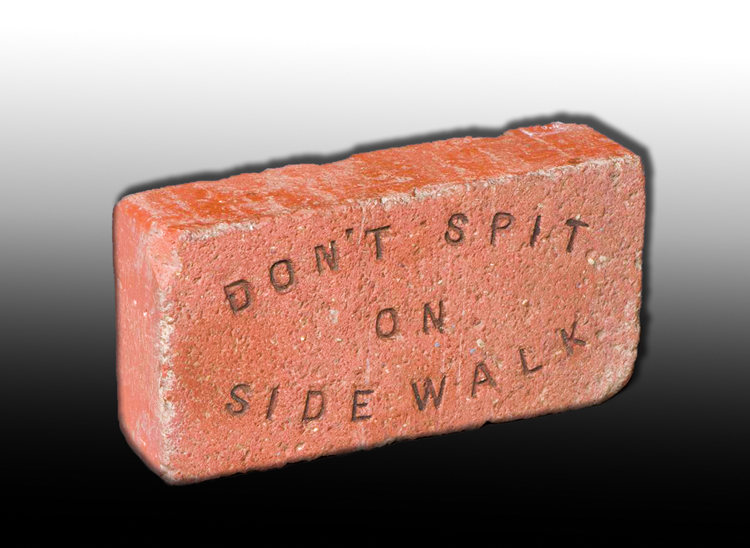

His targets in this campaign were common drinking cups and spitting in public places. He urged railroads and public facilities with drinking cups to replace their common cups with paper cups. He tested the cups from several trains and found they contained many kinds of bacteria, including tuberculosis. In 1909, the Kansas was the first state to ban the public drinking cup. He wanted brick manufacturers to stamp bricks used in building sidewalks with “Don’t Spit on Sidewalk.” Crumbine believed this practice of spitting helped spread tuberculosis. It was rumored one brickmaker, Capital City Vitrified Brick and Paving Co., agreed to stamp every fourth brick with the slogan just to get Dr. Crumbine to leave them alone.

Crumbine also tackled the issues of clean water and sewage disposal. It was common for towns to pump raw sewage into the most convenient waterway. Kansas passed water and sewage laws in 1907. In 1911, he urged hotels to change their sheets daily.

Crumbine used various methods to get Kansans to support his efforts. He used the State Board of Health Bulletin to spread his messages, beginning each bulletin in 1913 and 1914 with a series of short sayings to get local public health officials to act. These included:

The animal that eats at your table—the fly

The man who harbors a breeding place for flies is an enemy of society

Fingernail biters—bacteria eaters

The unscreened home is the season’s greatest danger

Civic cleanliness has its own reward—community health

A “swat” in the early spring saves many times “nine” in the summer

Crumbine and his staff developed stereopticon lectures on various public-health topics that could be used by local officials across the state. He made numerous talks on his favorite subjects. The Topeka woman’s club asked Crumbine to prepare an outline for a study of public-health conditions, which became popular across the state, and the Board of Health’s supply of pamphlets on various topics was soon exhausted. Other states became interested, and Crumbine, who was serving as president of the Conference of State and Provincial Boards of Health in 1914, called for a committee to develop such a course of study for the United States. The American Medical Association supported the effort and was responsible for distributing the 19-lesson course. To try to encourage local action, the final lesson was titled “A Study of our Town,” to be used to identify community problems.

In 1923, Crumbine moved to New York to become executive director of the American Child Health Association. He later worked for the Save the Children Foundation. He died in 1954.

Samuel Crumbine was a relentless campaigner on any issue he felt endangered public health. Many of his campaigns were aimed at preventing the spread of communicable disease. During Crumbine’s 19-year tenure with the Kansas Board of Health, the state’s death rate continually decreased. His public-health innovations made Kansas a leader in protecting the health of its citizens, and his contributions were implemented across the United States.