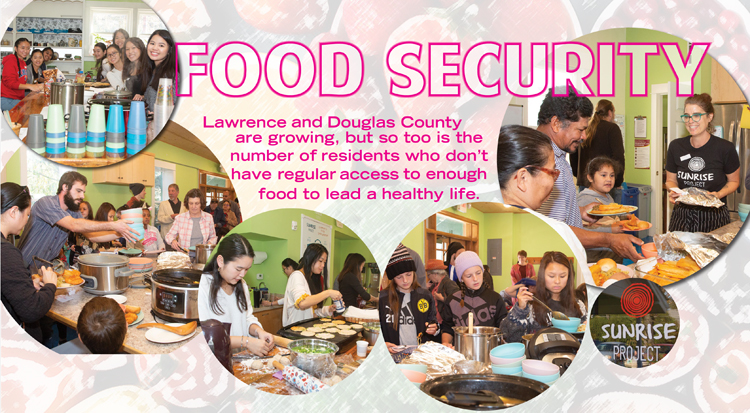

Lawrence and Douglas County are growing, but so too is the number of residents who don’t have regular access to enough food to lead a healthy life.

| 2019 Q4 | story by Anne Brockhoff | photos by Steven Hertzog

Food Festival Lunch was provided by community members from around the globe. Sunrise founder Melissa Freiburger (top right) smiles while bringing out another plate of international cuisine.

Lawrence and Douglas County have much to be proud of, from top-ranked universities to a growing population, dynamic retail environment and strong real estate market. That makes this truth hard to swallow: Almost 16% of the county’s residents aren’t sure where their next meal is coming from.

According to a 2017 study by Feeding America, the country’s largest domestic hunger-relief organization, 18,730 people here don’t have consistent access to enough food for a healthy, active life. They span all ages, ethnic groups and educational backgrounds. Some have jobs; some don’t. Many also struggle variously with health care, transportation and housing. In short, hunger fits no profile.

“Hunger looks like everyone,” says Ryan Bowersox, director of outreach and marketing for Just Food, a Douglas County food bank that serves about 13,000 clients a year. “They’re the students outside Henry’s (Coffee Shop). They’re bus drivers, service-industry workers and

Just Food, together with the Douglas County Food Policy Council, Sunrise Project, school districts, businesses and countless other organizations and volunteers, is dedicated to eradicating hunger in Lawrence and Douglas County. Doing so is essential to building a healthy community and robust economy, says Jude McDaniel, a founding partner of McDaniel Knutson Financial Partners.

“We have to find a way to support people that empowers them to take control over their own lives,” McDaniel says. “We have to help them get jobs, get food, get housing. That’s what a good community does.”

There’s clearly a need. Just Food’s total client visits rose 15% last year, and the number of seniors served has jumped two-thirds over the past four years, according to its 2018-19 annual report.

People might earn too little to buy enough food, or they’ve lost their job or had an unexpected expense. Sixty-one percent have suffered temporary financial setbacks that could become intractable but for the availability of food assistance, says Elizabeth Keever, Just Food’s executive director.

“They hit a bump in the road and need something to help them get by,” she says. “We’re preventing them from sliding deeper into a difficult economic situation.”

clockwise from top left: Just Food-Information and help desk inside the Just Foods store; Jude McDaniel, founding partner, McDaniel Knutson Financial Partners; Just Foods volunteer stocks the shelves in the Just Food store; Volunteers organize pack-aged goods to be put out front for customers; Executive Director Elizabeth Keever sorts through fresh peppers in the warehouse.

A Comprehensive Approach

Just Food’s main pantry in East Lawrence is open four days a week. Smaller pantries, called cupboards, operate at elementary, middle and high schools; the University of Kansas (KU), Haskell Indian Nations University and elsewhere. In October, Just Food launched a mobile pantry called the Cruising Cupboard. It’s testing potential Lawrence sites now and will make monthly visits to Baldwin City, Eudora and Lecompton.

There are classes on preparing healthy meals for less than $2 a serving and a community garden. The Pots and Pan-Try offers necessary kitchen equipment, and KitchenWorks trains young people seeking a career in the hospitality industry.

Food recovery is also key, and Just Food in 2018 recovered $2 million worth of food that would have otherwise been thrown away. Keever says while some area supermarkets and eateries, including Limestone Pizza Kitchen and Bon Bon!, have food recovery built into their business plans, others find it difficult.

Donors receive a $1.68 tax credit for each pound of food donated, but rules about what can be donated and how vary depending on the source. Keever hopes a tool kit being developed by Susan Harvey, an assistant professor in KU’s school of education, will simplify the process and encourage more restaurants, institutions and convenience stores to participate.

“It doesn’t hit the landfill, there’s a tax benefit, and it’s something Douglas County cares about,” she says.

Just Food’s comprehensive approach appeals to McDaniel, whose company is among Just Food’s financial donors. But the main reason it backs the organization? Its chief compliance officer and chief operations officer, Karey Chester, is also Just Food’s treasurer.

“Karey is so passionate about Just Food,” says McDaniel, who notes the company offers all employees two paid volunteer days a year. “They’ve turned into being a great partner for us.”

Any cost to McDaniel Knutson is more than offset by the good such involvement does, McDaniel says.

“We have found that anything our staff gets involved in that causes them to grow experientially, emotionally and socially—it all comes back into how they deal with clients,” she says. “We all benefit from that, plus it makes our community better.”

Jessica Cooney (client services) and Ryan Bowersox (marketing and outreach) operate Stuff the Bus for Just Food in The Merc parking lot.

Solving the Hunger Equation

The hunger equation is complex, though. Issues like housing, sales taxes, transportation and health care have an outsize impact on people struggling with food insecurity. Businesses have a stake in solving those problems, because the outcome directly impacts Douglas County’s economic vitality, says Kim Criner Ritchie, the sustainability and food systems analyst for Douglas County.

“If you’re a business owner, and you rely on tourism and people coming to participate in this community, the more vibrant and healthy it is, the more attractive it is to people who want to live and work here,” says Ritchie, who is also the county’s liaison to the Douglas County Food Policy Council (DCFPC).

Formed in 2010, the DCFPC is a joint Lawrence-Douglas County advisory board that counsels elected officials on both barriers and opportunities throughout the local food system. Its Food Policy Plan, adopted in 2017 by the Douglas County Board of Commissioners and the Lawrence City Commission, addresses all facets of how food is produced, bought, eaten and disposed of.

The DCFPC is now working to implement the plan, and its several working groups are open to the public. One focuses on agricultural practices and economic development, and another explores ways of reducing food waste. A third is tackling food access and equity.

“We do have so many resources and have so many progressive organizations and people that it’s easy to overlook that there are challenges,” explains Ritchie, who adds that the group held a community gathering in November to update the public on its work. “Hunger and food access are big problems.”

They’re also linked to other issues. Food insecurity correlates to higher rates of chronic diseases such as diabetes and high blood pressure, and increased medical costs. Housing and transportation take a bite out of family food budgets. Seniors living on a fixed income might have seen their savings slashed by the recession of 2008 or are trying to help their own kids financially.

“People seem to have this attitude that you need to go help yourself, that if you’re not helping yourself, you’re lazy, or you didn’t save,” says Michele Dillon, the Jayhawk Area Agency on Aging’s Douglas/Jefferson County lead and a member of the DCFPC’s health equity working group.

Rural areas present even bigger obstacles to people who don’t have reliable transportation or who live far from a grocery store. Outside of Lawrence, only Eudora and Baldwin City have supermarkets; the Perry-Lecompton Thriftway closed in late 2018.

Dillon, whose agency provides nutrition and other services to seniors, urges business owners to study and seek opportunities in underserved areas. Get to know your neighbors, she says. Find out what they need and be creative in helping them.

“Everybody looks at the big picture then thinks, ‘I can’t help everybody,’ ” she says. “Well, you can’t. But you can help the people in your backyard or the people in your neighborhood.”

(top to bottom) L-R Michael Steinle, Hugh Carter and Kim Criner Ritchie listen together at a com-munity meeting hosted by the Douglas County Food Policy Council in the Santa Fe Depot; Michael Steinle, the acting chair of the DC Food Policy Council, gives the public an update on the local food system plan; Members of The DC Food Policy Council meet in Eudora.

Fueling Change Through Food

That’s certainly Sunrise Project’s goal. The nonprofit fosters a sense of community among people from diverse cultures, neighborhoods, ages and socioeconomic status while gathering them together to cook, grow and share food.

“Our foundational goal is building an equitable community,” says Melissa Freiburger, who helped launch Sunrise Project almost six years ago in a former garden center at 15th and Learnard streets and is now its executive director. “We use food as a powerful lever to bring people together and build social justice.”

More than 100 people typically attend twice-monthly, free community meals, which are financed in part by a Sunflower Foundation grant and prepared by volunteers. One recently featured Indian food; another was an international festival with traditional dishes from China, Thailand, Peru and elsewhere.

Events have included a pie auction, a Korean cooking class and a forum to introduce school board candidates. Community coordinators collaborated with the DCFPC to gather input for the Food System Plan, developed a leadership training program called Activate Your Voice!, enabled by a Kansas Health Foundation grant and work to engage both volunteers and area residents.

Sunrise Project also grows food, both in its on-site garden and at two orchards near Burroughs Creek. All are maintained by staff and volunteers, and there are regular workshops and volunteer days where people can learn as they help. There’s no charge for harvesting food—anyone can take what they need for free.

“It’s an alternative model that exists outside the system of purchasing food,” Freiburger says. “You don’t have to fill out a form to prove you’re deserving of it.”

Kids are another priority. Sunrise Project conducts lunchtime tastings at area schools (one in September introduced the applelike jujube, pawpaws and okra), as well as cooking sessions where students learn to make pasta or burritos right in their classrooms.

“When you work with schools, you’re reaching kids from all backgrounds,” Freiburger explains. “This is just democratizing engagement with food for all the kids to have that experience.”

Sunrise Project strives to complement USD 497’s school garden program by assisting with those at the Cordley and New York elementary schools, and it will help install one at Kennedy Elementary this year. All of the district’s elementary and middle schools will then have their own gardens except for Sunflower Elementary; that one is waiting on grant approval.

Both high schools have greenhouses and hope to add gardens in the future. In addition, the district buys local food for school cafeterias and has a garden-based curriculum, Farm 2 School field trips and related initiatives.

“It’s important for students to learn about and to take an interest in the foods they are putting in their bodies,” says Scott Cinnamon, Cordley Elementary School principal. “It’s also important for students to understand that we are all a part of the community and to learn how they can contribute.”

Businesses including Cottin’s Hardware & Rental have also embraced that message. Owner Linda Cottin has long held a weekly farmers’ market in the store’s parking lot, and about a decade ago, she spearheaded a “100% local” lunch at Cordley. Throwing her support behind Sunrise Project by donating supplies, helping secure grant funding and serving as a networking resource was a natural move.

Everybody deserves healthy food, and communities are responsible for making sure people have access to all the necessities of life, Cottin says. If business owners need another reason to get involved, she has one word for them: sustainability.

“If we look at sustainability as a community, as a business owner, the only way I’m going to be able to maintain a business is if I have customers who have jobs, can afford to live around here and are healthy enough to stay alive,” Cottin says.

- LINKS

Feeding America statistics – click on Douglas County to see the numbers

feedingamerican.org

Just Food, justfoodks.org

Douglas County Food Policy Council DCFPC

Sunrise Project Sunrise Project

Jayhawk Area Agency on Aging’s Douglas/Jefferson county Aging