Though still segregated, blacks in early Lawrence were able to create a community for themselves, some even rising to prominence.

| 2019 Q3 | story by Patricia A. Michaelis, Ph.D. Historical Research & Archival Consulting | photos by Steven Hertzog

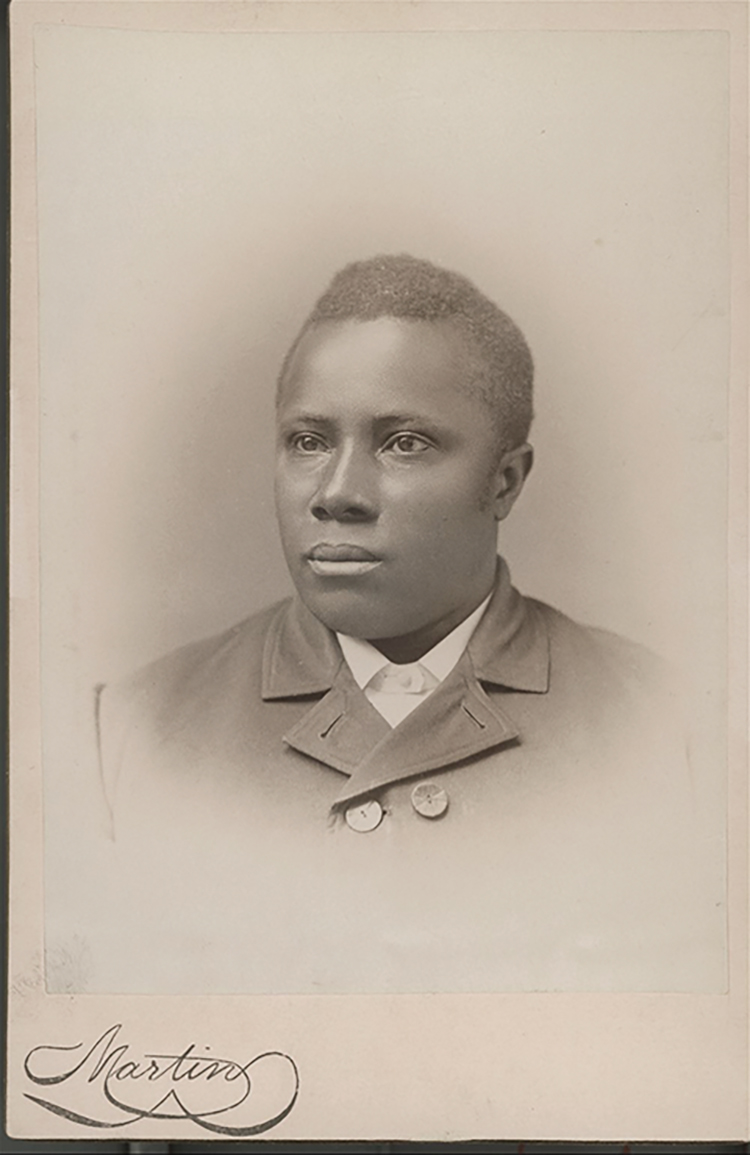

John Lewis Waller, 1850-1907. Born into slavery, Waller overcame his humble beginnings to become an accomplished lawyer, journalist, politician and diplomat. He migrated to Kansas in the spring of 1878.

Since it was founded by abolitionists in 1854, Lawrence was known as a free state stronghold. This made it attractive to free blacks and escaped slaves from Missouri and other border states. Lawrence was a stop on the underground railroad along with Quindaro, Topeka, Oskaloosa, Holton, Mound City, and Osawatomie. “Conductors” would guide escaped slaves from a safe houses in one community to one in the next. The underground railroad routes ended in Nebraska and Iowa. During the Civil War, several black militia units from Kansas fought to end slavery. At the end of the Civil War, Lawrence continued to attract former slaves and a number of blacks who had served in the conflict. The African American population in Lawrence grew from 25 in 1860 to 936 in 1865. Because of continued emigration of blacks, by 1880, 2000 African Americans lived in Lawrence. The federal census of that year listed the total residents of Lawrence at 8,510, so African Americans comprised about 25 % of the city’s population. That number remained relatively constant through 1900. By the mid-1880s, the time focus of this article, most blacks lived in North Lawrence or the East Bottoms, adjacent to the Kansas River.

Because blacks were a sizable segment of the Lawrence community and, since “separation” if not outright segregation existed, African Americans created their own institutions and community organizations. Traditionally, black churches have been crucial to African Americans creating their own sense of community and culture, and Lawrence was no exception. The 1886 city directory for Lawrence listed 3 black churches: the African Baptist Church at the northwest corner of Ohio and Warren, the Second Congregational Church on Kentucky between Henry and Warren, and St. Luke’s African Methodist Episcopal Church located on the southeast corner of New York and Warren. Lawrence had a segregated Grand Army of the Republic post, the Western Star Lodge #1 of the Knights of Pythias, an Odd Fellows Lodge, mutual and benevolent aid societies, Masonic lodges, and women’s clubs.

Also supporting the black community were two short lived African American newspapers: the Western Recorder, published from March 17, 1883 to November 6, 1884, by John L. Waller, and the Historic Times, owned and edited by C. H. J. Taylor. Lawrence residents also had access to the Topeka Plaindealer, a black newspaper published in Topeka. The availability of theses newspapers and the existence of mostly black neighborhoods contributed to the election of John Waller in 1883 to a seat on the Lawrence Board of Education. He represented the sixth ward and won by a significant majority. The Western Recorder credited the women in the African American community for helping secure Waller’s election as well as victories for several whites considered friendly to blacks. Though unable to vote themselves, these woman hosted dinners for friendly candidates and they ensured that their husbands voted. The Western Recorder published the following on April 4, 1883: “These ladies deserve much praise for their fidelity to principle. They labored the live long day for the success of the Republican ticket on behalf of the colored voters of this city.” However, one successful candidate was unable to make much of an impact on issues of interest to African Americans.

The schools in Lawrence reflected the segregation of the city as a whole. In fact most cities in Kansas with a sizeable black population followed the doctrine of “parallel development.” (This was later referred to as separate but equal and it was not resolved until the U. S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka in 1954.) Lincoln Elementary was located in North Lawrence and was believed to be the only school attended by blacks and taught by African American teachers. In an article titled “Breaking Ground in Canaan: African American community in Lawrence, 1870-1920” Paul E. Fowler III describes the situation for black students as follows:

- Other elementary schools offered all-black classes, occasionally taught by African-American teachers, yet only when there were enough students in a single age group. When there were too few students to form a full class, black children would attend the same classes as white children; however, administrators and teachers used segregated seating charts to physically separate the students. .

It can be difficult to find much information on blacks in the nineteenth century. Census records and local directories are some of the few primary sources that provide names and occupations of African Americans. The 1886 Lawrence City Directory provides a brief look at the African Americans living there. According to the customs of the time, listings of the names of black residents was followed by col’d in parentheses to indicate the person was colored. The majority of the men did some form of labor although various jobs were listed. Over 140 men were listed as laborers and over 40 were teamsters and wagon drivers. Over 30 men were listed as farmers, though many were probably truck farmers. Skilled trades included 13 blacksmiths, 12 barbers, and 8 men employed as painters and plasterers, glaziers, and stone masons. Seven African American men worked in railroad related trades as section hands and at the Santa Fe depot. Others worked at hotels as cooks, servants and handy men. Two men were listed as working for the post office—one a mail carrier and the other a postal clerk. One black was a member of the Lawrence police department and one as a physician. At least five men worked at feed and livery stables or as hostelers. There were 4 butchers, 4 janitors, three pressmen, 3 making boots and shoes, and 1 quarryman. Several worked in restaurants and or for grocers.

African American women listed in the 1886 Lawrence City Directory were few. Husbands were listed but not wives. However, over 40 black widows were include in the directory. Two women were listed as dressmakers, 6 were identified as domestics, and 4 were listed as doing washing. One woman was listed as a midwife.

However, all was not well between the Lawrence African American community and some segments of the white community in the 1880s. Blacks, with few exceptions, were poorer than the white population. Few owned their own homes with many families renting homes. Single blacks often lodged with black families. Dr. William M. Tuttle, Jr. wrote about African Americans in Lawrence in an article titled “Separate but Not Equal: African Americans and the 100-year Struggle for Equality. In Lawrence and at the University of Kansas, 1850s—1960.” He described the situation for blacks in Kansas and Lawrence as follows: “For African Americans the state of Kansas has always functioned on two levels, one symbolic and romanticizes, the other harshly real and truly unfortunate. . . .Once in Kansas, however, African Americans encountered the unrelenting force of the color line. . . .The conflict between lofty ideals and racist realities has been a central theme of African American history of Kansas.” This was true in Lawrence as well and is illustrated by the lynching of three African American men in 1882. A black woman was assaulted by a white man. Three black men murdered him and tossed his body into the river. The three men were arrested and an angry crowd of 300 men gathered at the jail. Initially, This group was dispersed but, the three men arrested were later were taken from the jail and lynched by a mob of approximately 50 white men. Rev. Richard Cordley, minister of the First Congregational Church and one of those in Lawrence who encouraged settlement by blacks, expressed the dismay of the lynching in a letter to the editor of the Lawrence Journal. He wrote about “the terrible tragedy which has just disgraced Lawrence and the State. . . .For Lawrence stands for Kansas, and the best in Kansas, and this terrible deed will go abroad to our shame. . . .” Cordley also addressed the lynchers with “You say ‘you are sorry. That is a feeble word. The blood of every law abiding citizen should tingle with shame, and his face blush with horror at such a deed.”

In spite of incidents such as this, African Americans in Lawrence continued to build a strong, but separate, community. Additional black businesses were established and several blacks worked as professionals. Two lawyers, Robert B. McWilliams and John W. Clark had offices at 730 Massachusetts and were members of the Douglas County Bar Association. Sam Jeans, an African American, served as assistant chief of police. Two black doctors were practicing in Lawrence at the turn of the twentieth century. Thus, in Lawrence in the 1880s and 1890s, some African Americans gained some economic stability, many children were educated while dealing with various aspects of segregation in the schools, black businesses served their neighbors and black churches and other institutions and organizations provided support and encouragement for a strong African American community in Lawrence.