Using and managing currency in territorial-era Lawrence was very different than today.

| 2019 Q1 | story by Patricia A. Michaelis, Ph.D. Historical Research & Archival Consulting | photos by Steven Hertzog from the Kansas State Historical Society, kansasmemory.org

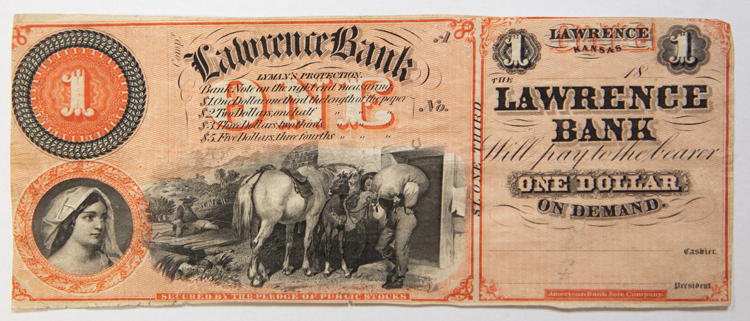

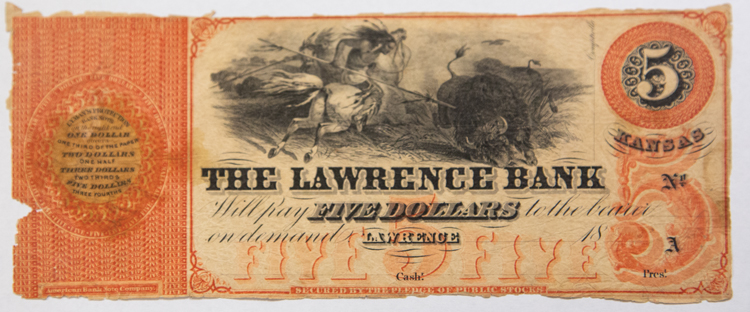

Today, we take for granted the fact that currency and banks are stable, but this was not the case in the Kansas Territory. The federal banking system wasn’t created until Congress passed the National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864. Until that time, states were responsible for authorizing banks and issuing their own currency. The first bank in Lawrence was founded during this era of territorial and state oversight before federal banks were established. On Feb. 11, 1858, the Lawrence Bank was incorporated by the territorial legislature along with the Bank of Leavenworth and the Bank of Wyandotte. Each of these banks could issue stock worth $100,000 and, divided into shares of $100, were authorized to issue circulating currency. The Lawrence Bank were issued currency in various denominations, but only bills for $1, $2, $3 and $5 are known to survive, according to “Kansas Paper Money,” by Steven Whitfield. These bills had engraved illustrations depicting a prosperous community with agricultural interest, a steamboat, factories and a Native American hunting buffalo.

The Lawrence Bank opened for business in May 1860. The bank was located on the east side of Massachusetts Street, across from the Eldridge Hotel. Original incorporators included Shalor Eldridge and James Blood. Principal stockholders were Robert Morrow, Charles Robinson and Robert S. Stevens. The first cashier of the bank was Ethan Allen Smith, who had come to Kansas from Wisconsin.

These directors and stockholders were all involved in the development of Lawrence as a prosperous city in Kansas during the territorial and early statehood periods. Their activities and influence circulated throughout the community just as the currency issued by the Lawrence Bank did.

The Eldridge name is still known in Lawrence because of the Eldridge Hotel, owned by Shalor W. Eldridge. A native of Massachusetts and a Free State supporter, Eldridge arrived in Kansas City on Jan. 3, 1855. In early 1856, he leased the Free State Hotel in Lawrence. In 1857, he and his brothers built the Eldridge House, which was burned during Quantrill’s raid. Eldridge was elected a city councilman in 1858. In 1857, Eldridge established a daily stage line from Kansas City to Topeka, Lawrence to Leavenworth, and Independence, Missouri, to Weston, Missouri. During the Civil War, he served six months as lieutenant in the Second Kansas Volunteer Infantry Regiment. In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln appointed him a paymaster in the United States army, and he filled that office until he resigned about a year later. In 1868, Eldridge was appointed quartermaster general by the Kansas Legislature. In 1869, he was elected county commissioner of Douglas County and, in the same year, was elected city marshal of Lawrence.

James Blood, another incorporator, was also active member of the community. He was born in Vermont, grew up in New York and moved to Wisconsin as a young man. Blood became an agent for Amos A. Lawrence, treasurer of the New England Emigrant Aid Co. (NEEAC) and moved to Kansas in 1854. He assisted the members of the first party of the NEEAC as they settled in Lawrence. He was actively involved with the Free State movement as a supporter of the Charles Robinson faction. He served as treasurer of the Kansas State Central Committee from 1856 through 1857. He was elected to the territorial legislature in Topeka in 1856. Blood was a member of the Wyandotte Constitutional Convention committees on corporation, banking, ordinance and public debt. Other civic duties included serving as the first mayor of Lawrence in 1857, as Douglas County treasurer 1864 to 1868 and as a representative from Lawrence in the 1869 Kansas Legislature. He was also a member of the board of trustees for “The Lawrence University” and its successor, the University of Kansas. During the 1870s, he lived at 1015 Tennessee St., and the striking red brick home still stands today.

Charles Robinson is the best known of the Lawrence Bank stockholders. Born in Worcester County, Massachusetts, on July 21, 1818, Robinson was an agent for the New England Emigrant Aid Co. and was involved in bringing people to the Kansas Territory to settle. He was one of the founders of Lawrence and served as governor of the Kansas Territory, the result of an election held by the Free State Party that was challenging the official proslavery government in Lecompton. He was the first governor of the state of Kansas, serving one term from 1861 through 1863. He is credited by historians for his moderate leadership in helping transition Kansas from its turbulent territorial era to statehood.

Another major bank stockholder was Robert Morrow. He was born in Sparta, New Jersey, on Sept. 20, 1825. He moved to Lawrence in August 1855 and was an active Free State supporter. He built the Morrow House in 1856 and opened it in the spring of 1857. (It was burned during Quantrill’s Raid in 1863.) Morrow was a member of the territorial legislature in 1858 and was a member of first state senate that was organized when Kansas became a state. He served several terms on the Lawrence City Council, including one term as president. He served as Douglas County treasurer from 1878 through 1882.

Robert Stevens, the third stockholder, was a speculator and a politician who moved to Lawrence from Lecompton. Born in Attica, New York, Stevens emigrated to the Kansas Territory in 1856. Because he had been a loyal supporter of his presidential campaign, President James Buchanan rewarded his loyalty by appointing him special U.S. Indian commissioner. His task was to arrange for the sale of Kaskaskia, Peoria, Piankeshaw and Wea tribal lands, ceded to the United States in 1854. Stevens also served as mayor of Lecompton in 1858. Already a stockholder in the Lawrence Bank, Stevens moved to Lawrence in 1862 to become a bank president, and he bought out the other stockholders around that time. Also in 1862, he filled a vacant seat in the Kansas Senate but did not run for a full term. Stevens finished that term not seeking reelection. Stevens was one of the few men spared during Quantrill’s raid on Lawrence in 1863.

All of these men were involved in the establishment of the Lawrence Bank, but its existence was short-lived. When Kansas became a state, the bank reorganized under state laws, but Charles Robinson and Robert Stevens became involved in a bond scandal that lead to the impeachment and acquittal of the first state governor on June 29, 1862. Shortly after the trial, Stevens deposited enough U.S. funds with the state to redeem the bank’s outstanding back currency. For a time, the bank operated as an exchange institution. Quantrill’s raiders robbed and burned the bank. It never reopened after the raid but continued to redeem currency presented for payment until it closed for good in January 1864.

The short but turbulent history of the Lawrence Bank illustrates that it could be difficult to establish traditional community institutions when founding a new city. While the Lawrence Bank did not survive, the city of Lawrence did, and the founders and stockholders of the bank played important roles in the growth and success of Lawrence as a thriving community in Kansas.