Some Lawrencians find helping those in impoverished countries fulfills their desire to give back.

| 2018 Q3 | story by Dr. Mike Anderson

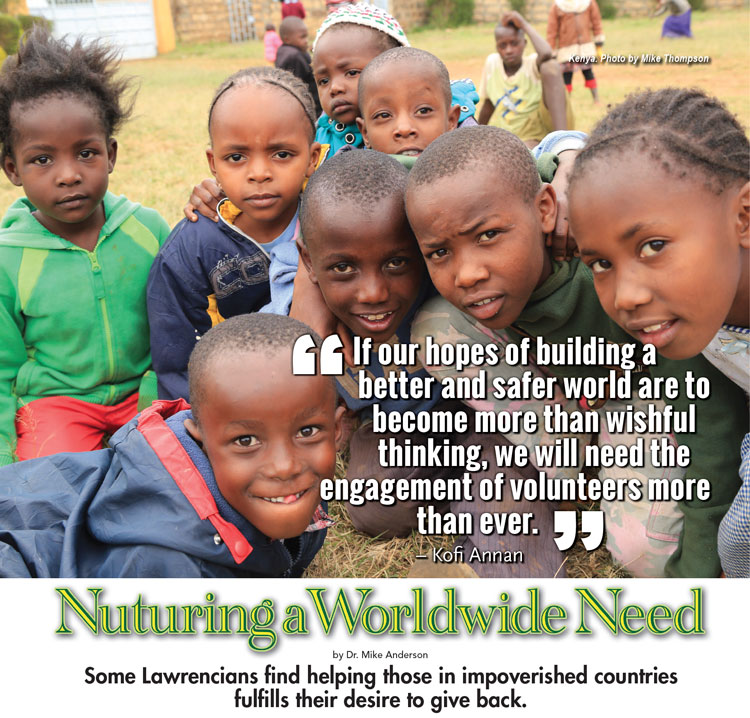

Kenya, photo by Mike Thompson

James is a Kenyan who grew up in a town called Maai Mahiu, which is translated to “hot water” in English. When he was 5 years old, he ran away from home, not because he hated his family but because he loved his sister. He left so his sister would get his rations of food and, therefore, wouldn’t be hungry. From age 5 to 10, he lived on the streets rummaging through dumpsters and begging for food. At age 10, he discovered an orphanage, one that clothed him and fed him and helped him get an education. He now provides lab resources for the local clinics in town and serves as an interpreter. That orphanage James found was largely made possible by the kinds of people who travel to some of the poorest and health-challenged countries in the world in order to do one thing: give.

Doctors work at a clinic in Kenya, photo by Dr Mike Thompson

From Kansas to Kenya

Kenya is the last stop on what is called the AIDS highway, which is an actual highway that also goes through the Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda. Truck stops that line this highway are filled with substance abuse, alcohol abuse and prostitution. And, the Kenyan town of Maai Mahiu is considered the worst of the worst. Forty percent of adults here are HIV positive. Hundreds of children are forced into the streets or orphanages when their parents die. Some will even contract HIV from their mothers.

Dr. Stephen Segebrecht is an ENT-otolaryngologist in Lawrence. Every June since 2005, Segebrecht has gathered a group of people to travel to Kenya in order to help. For the first six years, his group, K2K (a dual anachronism for Kansas to Kenya and Kenya to Kansas), aided the people of Maai Mahiu. It’s not uncommon for Segebrecht to see a grandmother taking care of six children because their parents died of AIDS. One grandmother, in particular, had a blood pressure of 220 over 148 (120 over 80 is considered normal). Without treatment, she would likely have had a stroke.

Taking care of these adults and children is the focus of Segebrecht and his team’s work. He sees people with compromised immune systems, parasitic diseases, upper-respiratory-tract infections, severe knee and back problems and gastrointestinal parasites. For the vast majority, Segebrecht is the first doctor they have ever seen. When food is scarce, parents feed their children “soil cakes,” which is literally just soil. Parasites from that soil get into children’s systems.

Doctors assist a patient at a clinic in Kenya, photo by Mike Thompson

K2K has put in water-filtration systems and slow-drip irrigation systems, and built grade schools. K2K also develops programs for public health, education, alcohol abuse and women’s rights. In most parts of Kenya, rape and battery against women are not seen as serious crimes. K2K spends time not just instructing women on proper nutrition but also helping them develop jobs and financial security. Segebrecht’s team offers these women refurbished laptops while teaching them about saving money and getting loans. These programs have helped the Kenyan economy by empowering women to lift themselves and their families out of poverty. “It’s possible to transform lives, bring hope,” Segebrecht says. “From their perspective, our presence there is nothing short of grace. Something they didn’t ask for, they couldn’t return the favor and undeserved. That hope and grace is transforming for us, as well.”

As you can imagine, it’s not easy to convince others in town to travel to Kenya every June. One of the people who saw value in this trip was Pat Parker, director of the pharmacy department at Lawrence Memorial Hospital (LMH). Ten years ago, Parker began traveling with K2K. Soon, he developed a relationship with the University of Nairobi School of Pharmacy (UoN). Here, he helped with post-graduate programming. Four years ago, he developed a program on how to teach students to vaccinate patients. He worked with UoN to build the program with the faculty at Nairobi. This was particularly important because pharmacists don’t provide vaccinations in Kenya, but the government wants to improve vaccination rates. Doing this work gave Parker the idea to include his students.

Tasha Wertin poses with two children in Haiti, photo by Stephanie Temple

Studies in the Field

The LMH postgraduate residency program for pharmacists now offers students the opportunity to work in Thailand or with the UoN in Kenya. Here, students gain valuable experience in leadership and management. While in Kenya, students have the opportunity to be in charge of the clinic and find themselves dealing with ailments not often seen in the U.S. It is common for them to see instances of malaria, worms and tuberculosis. Parker explains the experience is paramount to their profession and character. “It gives them a different perspective of our own health-care systems. It gives them a much stronger worldview and appreciation of what they have in the United States. It gives them a feeling of what the rest of the world pays for medicine,” he says.

Every year, Parker sees the direct impact Americans are making in this country. He tells the story of one nurse from Nebraska who was traveling with him. “Pat, I don’t know what I’m supposed to do. I’m an OB nurse. I deliver babies,” she told him. But, as he explains, on the second day, she delivered a baby. On the third day, a lady came into the clinic hemorrhaging and delivered a baby who was dead. The Nebraska nurse then spent the rest of the day helping the family through its loss.

The importance of students in struggling countries is not lost on the University of Kansas (KU). The Jayhawk Health Initiative (JHI) is a program aimed at providing prehealth students with an opportunity to enhance their prehealth knowledge by engaging in experiential learning and philanthropic experiences. Every couple of years, these students get to participate in a medical brigade, where they run clinics and provide health care to different countries. Their most recent brigade was in Panama. For seven days, these KU students see more than 700 patients.

In Panama, health-care issues abound. It is not uncommon to see an 80-year-old woman caring for newborn babies. The vast majority of Panamanians they treat have issues related to back and knee pain (from manual-labor jobs working in agriculture), nutritional problems because of bad diets (most Panamanians don’t eat fruits and vegetables because they are too expensive), hygiene (every patient who comes to the clinic goes home with a hygiene pack consisting of soap, toothpaste and toothbrush) and mental-health issues. Here, mental health is a growing problem and one that hasn’t been examined.

In Panamanian culture, mental health is not spoken about, which makes it tough to convince someone to open up about his or her problems. Savanna Cox , current executive director of JHI, was part of one of the medical brigades in Panama. In one instance, the brigade treated a little boy who wasn’t talking much in class. They brought the boy and his parents in to talk with a therapist. She marveled at how understanding the parents of the boy became and how relieved they were to finally understand what was going on with their son.

Michelle Carrillo, codirector of JHI, has also been on the Panama brigade. For her, JHI is not just helping with medical issues but also quality of life. On one particular occasion, she carried cinder blocks several miles to help a community build an outdoor shower for each house. She explains she was the only Hispanic child growing up in McPherson, Kansas, and was hesitant to speak Spanish in her town. In Panama, however, that ability meant something special. “For me, this program showed how much of an impact I specifically could make,” she says. “It reinforced my desire to work in public health. It helped flush out my identity as a person and who I want to be.”

Executive director Cox marvels at how, after returning from the brigade, most students came back with a greater appreciation of what they have in the United States. She says most came back with a vigor to do more in their communities, whether it be here in Lawrence or in more rural communities. “The experience with the brigade is eye-opening for things I’ve taken for granted, especially with health care,” Cox says. “Being a student, it gives me more motivation that this is what I want to do with my life.”

These brigades often mean helping some of the most struggling countries, but that also means security risks. This year’s brigade was supposed to bring upwards of 70 students to a town in Nicaragua from May 13 through 19. However, security issues over civil unrest in the region where the clinic would have been located cancelled the brigade. The University, along with the members of JHI and likely their parents, decided it was in the students’ best interests to cancel the 2018 brigade. For now, the students will have to wait awhile longer to make a difference on the international scale.

Doctors discussing eye glasses with patients at Kenyan health clinic; photos by Pat Parker

Poverty Abounds

Haiti is one of the poorest countries in the western hemisphere. According to the CIA, 80% of Haitians live in poverty. Perhaps no one in Lawrence knows this better than Tasha Wertin. Currently, she and her husband have seven children, all adopted, with another on the way. She was looking to do something more when she learned about a program called Kids Alive through the Lawrence Free Methodist church. Once or twice a year, Wertin visits the town of Cap-Hatien to help locals build houses in an orphanage. This past visit, she even helped build a school. The old school featured only a few rooms where the walls didn’t even go to the ceiling. “I always wanted to do something, but I didn’t know I could,” she says.

Eight years ago, a devastating earthquake ravaged Haiti. The earthquake took 316,000 lives and displaced more than 1.5 million people, the majority of which were children. Thousands among thousands of children who lost their parents came to Cap-Hatien seeking help. “Just to have a pillow is just huge for these children,” Wertin says. Many Haitian children are forced to sleep on the ground. They put one of their shirts on the concrete and try to sleep. The children there have little. Wertin explains just seeing a Band-Aid was huge for these kids. One of the children outside the orphanage was given a towel, and that child wore the towel every day, sometimes on his arm, sometimes around his neck. “He just had so much love and respect for that towel,” she says. A large number of these children only eat three meals a week.

Tasha Wertin works building with other volunteers in Haiti and helps tend to another women’s medical needs, photo by Pat Parker

The children in the orphanage, however, get three meals a day and a bed. The orphanage currently contains five houses and a school, all of which are surrounded by a wall for security. Each house can fit 12 children. Wertin explains parents are now faking death certificates so their child can go to the orphanage, because they know there’s a better life offered inside its walls. There are no shelters or food banks anywhere in the vicinity for these children. For this reason, Wertin adopted two Haitian girls—Guilande, 10, and Love-Findia, 9.

Adoption involves Wertin giving aid once a month to the girls. When she’s there, she often goes on walks with the girls. Guilande doesn’t live in the orphanage. She and Wertin often walk holding hands around the town (something Guilande wouldn’t do on her own). Wertin was later told that when Guilande knows she is coming to visit, she puts on her best clothes (which include jeans and a slightly stained T-shirt). Whenever a car comes on their walk, Guilande yanks Wertin’s hand and body away from the road. (Cars in Haiti are notorious for failing to yield to pedestrians.) The U.S. embassy in Haiti has labeled the roads “chaotic.” Poor road signs and the absence of traffic rules lead to extremely dangerous and unpredictable driving behavior. Outside the walls of the orphanage is a much different life for Guilande. This is why the goal is to build three more houses in the orphanage, which will allow 36 more at-risk children, such as Guilande, to live much more safely.

The experience of her work in Haiti has truly made a substantial difference in Wertin’s life. “Coming home and not trying to change our whole world was hard. To experience the severity of their situation is very humbling,” she says. “There is no electricity or plumbing. Everybody is almost always outside living with each other. I didn’t realize how secluded we are in our houses with just our families. We find our joy in our things, and they find their joys in each other.”