More companies opt to offer a “living wage” to employees to enhance their job performance as well as their quality of life.

| 2018 Q1 | by Liz Weslander photos by Steven Hertzog

The Merc

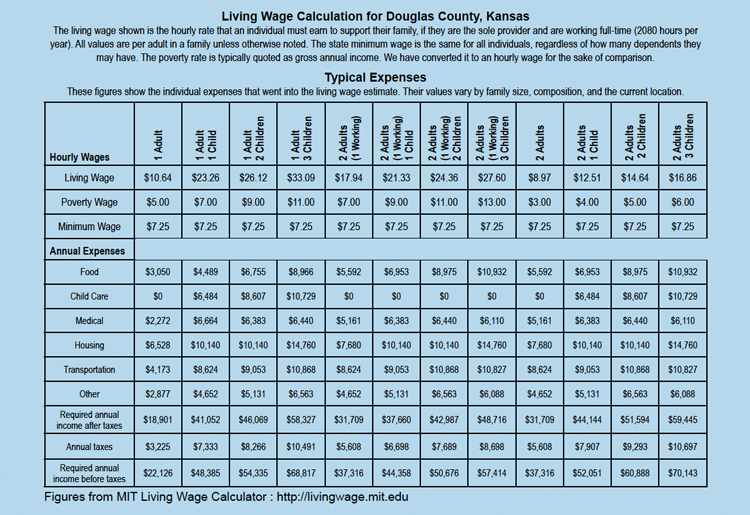

For almost 20 years, the United States’ federal minimum wage has been $7.25 per hour. While this might be OK for young part-timers working for extra cash, for full-time workers trying to support themselves, $7.25 is simply not enough. According to the MIT Living Wage Calculator, a full-time worker in Douglas County must earn at least $10.28 an hour to meet the bare minimum of living expenses for an individual. Add a child to that individual’s household, and the living wage jumps to $22.48 per hour.

While nobody expects to get rich off of entry-level wages, working full-time only to fall short of meeting basic expenses is, at best, discouraging and, in some people’s minds, unjust. In January, The Merc Co-op, a cooperatively owned grocery store at 901 Iowa St., implemented a new livable wage structure that enables its full-time entry-level employees to meet their living expenses and, hopefully, have enough to save a bit of money. While still in its early stages, Merc management says the shift has resulted in increased productivity, lower turnover and better customer service.

What Is a Living Wage?

There are a number of models for calculating a living wage, but the MIT Living Wage Calculator, created in 2004 by Amy K. Glasmeier, professor of economic geography and regional planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), is one of the most widely used. Glasmeier describes the Living Wage Calculator as an alternative way of measuring the minimum wage a person must earn to meet basic living expenses. Typically, policymakers use the federal poverty threshold to determine one’s ability to meet a certain standard of living. For instance, a household generally must earn at or below 130 percent of the poverty rate to qualify for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (food stamps). However, the poverty threshold does not account for geographical differences in living costs and only includes basic food expenses. In contrast, the MIT living wage model uses geographically specific spending data to determine minimum living costs in every U.S. county. It also accounts for expenses such as child care, housing, transportation, insurance and personal care items.

While MIT’s Living Wage Calculator website says its living wage model is “a small step up” from poverty as measured by poverty thresholds, it also makes clear the model reflects an austere, possibly stagnant, lifestyle.

“The living wage model does not allow for what many consider the basic necessities enjoyed by many Americans,” it says. “It does not budget funds for preprepared meals or those eaten in restaurants. It does not include money for entertainment, nor does it allocate leisure time for unpaid vacations or holidays. Lastly, it does not provide a financial means for planning for the future through savings and investment, or for the purchase of capital assets”

How Is The Merc Making It Happen?

Offering a livable wage to its employees has been a goal of The Merc’s management team for many years, explains Rita York-Henneke, The Merc general manager. After deciding early last year to make this initiative a priority, the co-op established a wage its leaders thought was “livable” for Lawrence, then determined what organizational changes needed to happen in order to hit that number.

When calculating its new livable wage structure, The Merc used the MIT Living Wage Calculator as a base but also looked at wage models created by the National Cooperative Grocers Association and the CDS Consulting Co-op. These models account for expenses that the MIT model does not consider, such as telephone, taxes and savings.

“Savings was a big deal for us,” says Zac Hamlin, human resources manager at The Merc. “The way that we looked at this is that an organization has the responsibility to create space for someone to dedicate 5 percent of their income to savings in order to provide something that looks like a cushion for those unexpected circumstances.”

Based on its research, The Merc settled on $12.35 as a livable wage for a single individual in Lawrence-nearly $2 more than the MIT Living Wage Calculator rate for Douglas County. Beginning in January 2018, all full-time employees earn at least $12.35 per hour with the option to purchase health, dental, vision and life insurance for about $100 per month. This wage is offered to new employees after a three-month training period, during which the hourly wage is $11 per hour.

Of course, creating this wage structure has involved a number of organizational changes and some patience on the part of existing staff. The primary change at The Merc has come in its training systems. Whereas in the past, Merc employees were trained in one department, they are now required to learn the ropes in multiple departments. One training path cross-trains employees on the front end, “center store” (grocery and wellness departments) and produce departments to work in any of those three areas.

“Those three big departments are essentially sharing staffing,” York-Henneke says. “Employees still all have home departments and still report to that department’s supervisor, but now, you will see someone working in the aisle who can also pop onto a register.”

The other training path at The Merc cross-trains employees in food services (the deli and bakery departments) and the meat and seafood department.

The Merc has based its new approach to training and wages on a model laid out in the book “The Good Jobs Strategy,” by Zeynep Ton. In a nutshell, Ton argues that old-school business philosophies view employees as inputs and expenses-low skills mean low wages, which lead to higher profits. However, Ton argues that it is possible, and even savvy, for businesses to significantly increase the responsibility of entry-level positions and then pay these employees a higher wage. She cites national retailers QuikTrip and Costco as two successful examples of this model.

“There are a lot of strategies in Ton’s book that will allow a business to pay good wages, be a really good employer, have excellent customer service and do well financially without increasing the prices of its goods,” York-Henneke explains.

York-Henneke and Hamlin agree The Merc has already seen some benefits to adopting a higher-expectation/higher-wage model, including increased efficiency, lower turnover and increased morale.

“Our hypothesis that staff really do want to continue to learn more and be good at their jobs is a reality, ” York-Henneke says. “This investment we are making in our employees is worth it. It’ s not just about being able to afford going out to eat or to save a little bit of money. The quality of life and pride in job makes a huge difference.”

And, The Merc has done all this without increasing prices.

By cross-training employees and through some natural attrition of staff, The Merc has been able to reduce its number of employees and consolidate a handful of part-time positions into full-time positions. In October 2016, The Merc had 113 employees. It now has 103, only six of which are part-time.

“Where we used to have four 30-hour people doing a task, we now have three 40-hour people doing a task instead. That saves a little bit on the benefits side,” Hamlin says.

Having more comprehensively trained employees also means that when someone does leave the co-op, The Merc is now more likely to be able to hire from within. Hamlin says that as of Jan. 24, The Merc had not had an open position in 82 days-more than 22 percent of a year. Reducing turnover is a big money-saver.

“This means that every single person at the co-op at this moment has made it through all of their initial training, which means we get to teach them the next thing instead of continually teaching the basics. We are retaining higher-performing employees,” Hamlin says.

Who Else Is Doing This?

While the City of Lawrence has had a living wage ordinance (Ordinance 7706) on the books since 2003, it only requires companies receiving tax abatements to pay wages that meet a wage floor determined by the city. This wage floor hourly wage, adjusted annually, is based on an annual wage equal to 130 percent of the federal poverty threshold for a family of three. The city’s wage floor for 2016 was $12.60 per hour; for 2017, it was $12.76.

In 2016, the companies required to meet the wage floor per Ordinance 7706 were Amarr Garage Doors, Grandstand Glassware + Apparel and Sunlite Science & Technology.

Gwen Denton, Grandstand’s human resources director, says Grandstand’s entry-level production position, quality inspector, pays competitively (within the wage floor) and offers the opportunity for advancement and benefits. Previous experience is not a prerequisite to be hired, and a training program is in place for an employee to become successful in this position.

Denton says offering a livable wage is essential to the company’s recruiting efforts, to staff morale and to the overall success of Grandstand. Livable wages can also have positive effects beyond the workplace, she believes.

“When people don’t have to struggle to feed their families and pay their bills, they can save for the future, purchase a home, start a family and contribute more to the community,” Denton says.

What’s Next?

While the initial results have been encouraging, York-Henneke says making organizational changes at The Merc has not been easy, and there is more work ahead to ensure the livable wage initiative is successful.

“I think there is a sense of loss for that easier, more chill job that used to exist, and there’s the fear that we are trying to do more with less,” York-Henneke says. “Our job as managers is to keep leading the way and showing people that we can do this; we just have to do it differently. It takes a lot of work and a lot of faith.”

Although 82 percent of existing Merc employees received a wage increase as part of the cross-training process, compensation for Merc management and a handful of middle-level hourly employees has stayed the same, resulting in some wage compression for those employees. York-Henneke says that although she thinks most people recognize that when you increase the lowest wages within a company, the spectrum of wages for all employees is going to shrink. Although York-Henneke believes this is actually something to celebrate, The Merc recognizes that seasoned, higher-level employees want to be compensated accordingly within any wage structure.

“This project is not done just because we have people making $12.35. It is a long game. We are looking very closely at the financials, and we want to make clear that the wage compression is going to be addressed” York-Henneke explains. “We are not talking about years before this happens but months or quarters. It’s not just about pay; it’s also about people’s pride.”

Hamlin and York-Henneke are hopeful their changes will inspire other local companies to also adopt a livable wage.

“Anyone could to it,” Hamlin says. “And, I’ll be honest, I hope that a year from now that The Merc is scrambling to find how we differentiate ourselves again, because every store in town has decided that paying livable wages is the right thing to do. I think there are real ramifications to the community if we can create positive pressure in that way. So, yes, we do hope that there are other stores that take this on.”