The law’s impact on prevention of gender discrimination is seen across nearly all aspects of women’s athletics.

| 2017 Q3 | story by Emily Mulligan, photos by Steven Hertzog

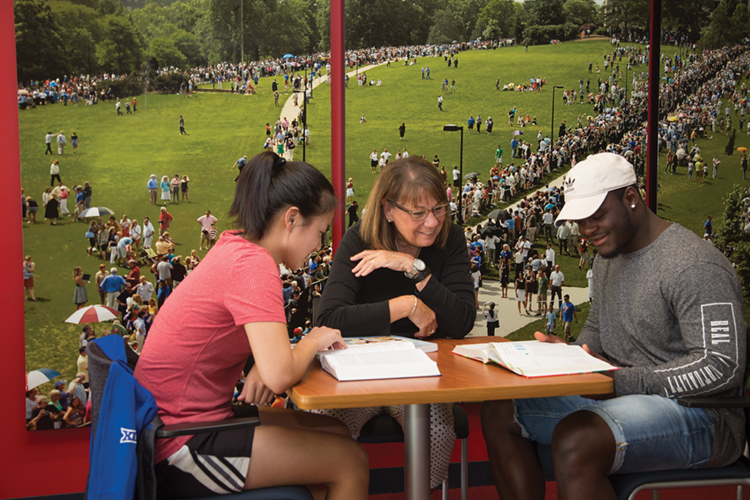

KU Women’s volleyball season opener at Horejsi Family Center Athletics

Most people outside of college athletics can rattle off a generalization about the law known as Title IX.

“It allowed girls to participate in sports.”

“Title IX made colleges cut and reduce men’s athletic programs.”

“Men’s and women’s sports have to have the same amount of money in their budget.”

“Programs for girls and boys in athletics have to be identical.”

All of these statements are both true and not true. Title IX is a section of the federal Education Amendments Act of 1972 and applies to all educational institutions—public and private, K through 12 and university level—that receive federal funds. This is the law, in its entirety:

- “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Title IX’s intent was to be applied broadly to educational opportunities, and it has had an impact on all aspects of education, including course offerings, financial assistance and housing, to name a few.

“When originally created, Title IX had influence over things well beyond sports,” explains Shane McCreery, director of institutional opportunity and access (IOA) at The University of Kansas. “Federal funds affected how schools implemented fields of study for both genders, but the law also applied to extracurricular activities, and that’s where sports came in. Sports were growing rapidly. Therefore, there was a demand and interest to enhance women’s opportunities to be equal to men’s.”

Title IX’s effect on sports participation and opportunities for girls and women has afforded some of its most visible and public impacts.

“If you talk to coaches from any university, when women’s sports were being formed, they were scrounging for any old T-shirts, for used uniforms and washing them themselves. Any female athlete now can’t relate to that,” says Jim Marchiony, associate athletics director, public affairs, with KU Athletics. “Now, fathers expect their daughters to have the same opportunities as their sons have.”

2017 marks the 45th anniversary of Title IX, and KU Athletics has its own related milestone to celebrate.

“This is the 50th year for competition for women’s sports at KU. We have the oldest women’s sports rivalry in the Big 12, which is KU and Kansas State women’s basketball,” says Debbie Van Saun, senior associate athletics director at KU Athletics.

Title IX in KU Athletics

With 45 years under its belt, Title IX provides a well-established protocol in college athletics. KU Athletics employs an outside professional Title IX consultant to audit and analyze the University’s athletics programs on at least a biannual basis.

Debbie Van Saun, Assistant to the Athletic Director works closely with student athletes.

Van Saun oversees the day-to-day and program-to-program Title IX elements of athletics, as needed, but she emphasizes that Title IX is by now as much a part of college athletics as practices and sweat. The thick binder of the law in all its detail is “institutionalized” at KU in a rigorous way, she explains.

Often, Title IX is colloquially interpreted to provide “equal” opportunities and funding in athletics. In truth, the law is about prohibiting discrimination, so applying Title IX in a purely financial sense does not fulfill the scope. So, it is not purely about budgets and dollars, and it can be difficult for those outside of college athletics to find the right words of comparison between men’s and women’s athletics programs. Words like “parity” and “equitable treatment” come the closest to reflecting Title IX’s intent.

Title IX at KU is best illustrated using the categories and aspects of college athletics where Title IX applies. All of these areas must refrain from discrimination on the basis of gender and provide the same opportunities to male and female student-athletes: facilities, roster management, coaching, sports medicine, travel, scholarships, equipment, housing, academic support and publicity.

One of the most public and visible effects of Title IX can be seen in terms of KU Athletics facilities. The construction of Rock Chalk Park in 2014 was as much about Title IX as it was about the expansion of KU Athletics facilities for track and field, tennis, softball and soccer. The same goes for the construction under way at the former Alvamar Country Club, now called the Jayhawk Club, which will be home to the KU men’s and women’s golf teams.

“Not too long ago, facilities for all those sports were not where they needed to be in terms of parity. Now they are. The thing I’ve been proud of is that we’ve had a plan,” Van Saun says. “We have made steps each and every year to track that plan. You can’t do every sport in one year—not everyone has a drawer full of money. The good news is now it’s not a situation where we’re starting from scratch.”

At KU, tennis is a women’s sport only. Rock Chalk Park’s recently completed Jayhawk Tennis Center has six indoor courts and six outdoor courts exclusively for the KU Tennis team, as opposed to being shared with the public, as courts were in the past. And, the indoor competition courts may be the most notable addition.

“Not too long ago, if it was raining, the tennis team would have to scramble and drive either to Topeka or Overland Park to host an indoor match,” Marchiony says.

The Jayhawk Club will provide both golf teams with locker room and practice facilities that are in line with other Big 12 golf teams, Van Saun says. The teams will also have equal access to gathering space and an indoor practice range, in addition to an improved outdoor practice range.

photo courtesy Jeff Jacobsen, KU Athletics

Prior to Rock Chalk Park and the Jayhawk Club, the 2008 construction of the Anderson Family Football Complex at Memorial Stadium also prompted some Title IX facility updates to the training room in Wagnon for female athletes.

“We have people who come back for K-Club reunions who aren’t aware of all of our facilities. Before the Boathouse was built, the rowing facility was a porta-potty and a chain-link fence. The group rowing this fall have always known the Boathouse,” Marchiony says.

One of Title IX’s aspects that takes the most administering year to year and sport to sport is roster management, Van Saun explains.

The law requires the participation rates of female athletes and male athletes line up with the ratio of full-time undergraduate female students to male students enrolled at the University each year. So, Van Saun must analyze each sport’s roster numbers to make sure KU Athletics is fulfilling that obligation while also factoring in Title IX’s requirement that athletic scholarship dollars remain equal for both genders. Generally, the solution is the addition of (or subtraction of) walk-on participants, particularly in football, men’s and women’s track, and rowing.

Van Saun’s other constant Title IX responsibility is maintaining equity among the coaching staffs of each sport. Title IX does not stipulate how many coaches of each gender must be employed; rather, the number of coaches for each sport must be proportionate, and the office space and courtesy cars, for example, must also be equitable.

Title IX’s Impact on Student-Athletes

Maintaining and enforcing Title IX in college athletics can no doubt be complicated, but the opportunities and experiences the law has afforded countless female athletes cannot be quantified.

“The reality is, without female sports, there wouldn’t be male sports in the same way. It’s good for intercollegiate sports in general to have both genders in sports,” Van Saun says. “Frankly, our guys here expect to see both sexes in the weight room and on the field of play. That’s what they’ve grown up with.”

KU Hall of Famer and senior Director of K Club and Traditions Candace Dunback

Candace Dunback, a KU All-American and Academic All-American in track and field, credits Title IX not just for her experiences in sport but also for helping her become who she is as a person.

When she was a child in the small town of Nevada, Missouri, in 1986, Dunback (then Candace Mason) saw a flier for a track meet 1½ hours away and begged her mother to let her compete. That track meet led to Dunback joining a club team and, ultimately, competing all over the country before she graduated from high school.

Because Title IX and women’s sports were well established, Dunback was the beneficiary of opportunities that even her older siblings had not had.

“It opened up my world through sport. I came from a small town with a lack of diversity, and I became able to see people as people, not for their skin color or economic status or religion,” she says. “Having a full-ride scholarship to KU, I earned that, but I’m very thankful for it. My parents worked very hard, but my trajectory in my life would have been very different.”

Even as well established as collegiate track and field competitions were by the late 1990s when Dunback was at KU, it wasn’t until her junior year at KU that pole vaulting became a women’s event.

“I had always been aware of who came before me, and I didn’t have to fight for all that I had like women before me,” she explains. “So, with pole vaulting, being a part of something new and getting to see ladies jump onboard and pick it up was special.”

Dunback holds the KU records for heptathlon and pentathlon, with previous records from the late 1980s.

“When I came through and was breaking records, those records wouldn’t have been there if the women hadn’t had the opportunity to compete. The records wouldn’t have been so hard to break,” she says.

Now, in her job as senior director of K Club and traditions for KU Athletics, Dunback gets to learn athletes’ stories and, often, meet the people from them.

“I hear stories from before my time at KU, when students’ parents had station wagons so they could drive the kids to games, and of them packing lunches so the athletes would have something to eat. By the time I came in, we were flying everywhere to competitions and had different shoes for all the events,” she recalls.

Dunback says today’s women’s track and field athletes are “hungry” for the old stories of what it took to get them where they are today.

“I mentor the track team, both men and women. I really hear no difference between the celebrations and the stresses, and the haves and have-nots between the genders,” she says. “I know that what they end up getting out of college athletics is much more than sports.”

Shane McCreery, Director of Institutional Opportunity and Access @KU

Title IX Across the University

The interpretation of Title IX as a law took what could be called a “pivot” in 2011, when the United States Office of Civil Rights issued a memorandum about the law. Now called the “Dear Colleague” letter, the memo stated that sexual harassment, including sexual violence, is a form of sex discrimination prohibited by Title IX. “Dear Colleague” set national standards and procedures for educational institutions to adjudicate student-on-student sexual assault.

“Title IX coordination existed prior to 2011, but it took on a whole new meaning after 2011,” IOA’s McCreery says. “Universities were tasked to find ways to do training to the student body on how to seek resources if they’ve been a victim of sexual violence or sexual misconduct, and also to be proactive on not assaulting or battering.”

McCreery’s office implements the Title IX adjudication procedures and publicity and training about the University’s resources for both the victims and the accused. And, “Dear Colleague” required people in his position to take a different approach with students.

“Prior to ‘Dear Colleague,’ we put the emphasis to the students on how not to put themselves in situations. So, this change required persons in my role to educate themselves on a topic that had previously been a police role,” McCreery says.

The IOA must function in a neutral role for both victims and the accused in sexual harassment situations. McCreery reports directly to the chancellor, and IOA is not tied to any academic departments or Athletics. IOA investigators serve the role of fact-finders and work to adjudicate each case as prompted by its circumstances and victim’s desires.

KU faculty, the Lawrence Police Department and Lawrence Memorial Hospital all are part of IOA’s information network to inform students, both victims and accused, that there is an on-campus department to provide them with resources and support. KU Athletics also must refer any sexual-harassment claims from students to IOA.

Because relatively few sexual-harassment victims report their attacks to any authority, IOA must also connect with students directly through training and traditional publicity.

McCreery came to KU a year ago and has designed a KU Title IX logo, as well as fliers and posters around campus in student-centric locations, to get the word out about both IOA and what particular actions—such as stalking—qualify as sexual harassment.

“It has been challenging. A lot of people in the student body don’t know what Title IX is. And now, it’s more of a support system and communication system,” McCreery explains.

KU Athletics has taken advantage of IOA’s resources extensively for its student-athletes.

“We make sure we’re doing the best job we can. We have taken our programs to the NCAA, and they’ve said we’re a model for other institutions. We don’t just stop at athletics and academics; we want to make sure we have good citizens,” KU Athletics Van Saun says.

171 Comments

slot siteleri en kazancl? slot oyunlar? slot tr online

slot oyunlar?: en cok kazand?ran slot oyunlar? – slot oyunlar?

az parayla cok kazandiran slot oyunlar?: slot oyunlar? puf noktalar? – slot oyunlar?

http://pinup2025.com/# пин ап вход

https://slottr.top/# en kazancl? slot oyunlar?

pinup 2025: пинап казино – пинап казино

az parayla cok kazandiran slot oyunlar?: slot tr online – az parayla cok kazandiran slot oyunlar?

https://pinup2025.com/# пин ап казино официальный сайт

пин ап зеркало пин ап вход пин ап казино официальный сайт

bet turkiye: dГјnyanД±n en iyi bahis siteleri – eski oyunlarД± oynama sitesi

en kazancl? slot oyunlar?: slot siteleri – slot siteleri

http://pinup2025.com/# pinup2025.com

medication from mexico pharmacy Best online Mexican pharmacy mexican pharmaceuticals online

https://indiapharmi.com/# top online pharmacy india

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: mexicanpharmi – medicine in mexico pharmacies

buying from online mexican pharmacy: Cheapest online pharmacy – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

https://mexicanpharmi.com/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

https://canadianpharmi.com/# ed pills for sale

indian pharmacy India pharmacy delivery cheapest online pharmacy india

http://mexicanpharmi.com/# reputable mexican pharmacies online

http://mexicanpharmi.com/# mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

ed products: Canada pharmacy online – prescription drugs online

best natural cure for ed: Best Canadian online pharmacy – ed meds online pharmacy

natural herbs for ed Canada Pharmacy erectyle disfunction

http://mexicanpharmi.com/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

india pharmacy: Best online Indian pharmacy – india pharmacy mail order

https://indiapharmi.com/# Online medicine home delivery

erectile dysfunction medicines Canada Pharmacy online reviews supplements for ed

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: Online pharmacy – reputable mexican pharmacies online

https://mexicanpharmi.com/# mexican rx online

https://indiapharmi.com/# Online medicine order

purple pharmacy mexico price list: Legit online Mexican pharmacy – mexican mail order pharmacies

herbal ed treatment canadian pharmi help with ed

https://mexicanpharmi.com/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

https://indiapharmi.com/# india pharmacy mail order

buying prescription drugs in mexico: mexican pharmacy – mexican mail order pharmacies

treatment with drugs: Canadian pharmacy prices – ed help

https://indiapharmi.com/# top online pharmacy india

mexican pharmaceuticals online Online Mexican pharmacy mexican mail order pharmacies

http://canadianpharmi.com/# dysfunction erectile

http://mexicanpharmi.com/# buying prescription drugs in mexico online

online prescription for ed meds: Best Canadian pharmacy – treatment of ed

reputable indian online pharmacy Best Indian pharmacy indian pharmacies safe

indian pharmacy: Online medicine home delivery – top online pharmacy india

https://mexicanpharmi.com/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

http://indiapharmi.com/# indian pharmacy paypal

where can i buy cipro online ci pharm delivery buy cipro without rx

https://clomidonpharm.com/# buy cheap clomid price

prednisone capsules: generic prednisone otc – india buy prednisone online

can i purchase clomid: how can i get generic clomid without insurance – can you get generic clomid without insurance

http://prednibest.com/# 10 mg prednisone tablets

https://cipharmdelivery.com/# ciprofloxacin generic price

prednisone 3 tablets daily prednisone cream brand name prednisone 15 mg tablet

https://amoxstar.com/# amoxicillin 500 mg capsule

buy cipro online without prescription: buy cipro – cipro online no prescription in the usa

where can i get clomid prices where to buy clomid online can you buy cheap clomid for sale

http://prednibest.com/# buy 10 mg prednisone

prescription for amoxicillin Amox Star amoxicillin 500mg capsule buy online

http://clomidonpharm.com/# can i buy generic clomid no prescription

where can i buy amoxicillin online: Amox Star – 875 mg amoxicillin cost

https://amoxstar.com/# amoxicillin generic

ciprofloxacin generic: ci pharm delivery – buy cipro

order clomid without rx clomidonpharm can i get clomid

https://prednibest.com/# prednisone canada pharmacy

where can i buy cipro online: buy cipro online canada – buy cipro online usa

cipro online no prescription in the usa: buy cipro cheap – buy generic ciprofloxacin

ciprofloxacin over the counter cipro for sale where can i buy cipro online

http://amoxstar.com/# price for amoxicillin 875 mg

amoxicillin 500mg capsules price: AmoxStar – amoxicillin generic brand

where can i buy cheap clomid without a prescription clomid on pharm buying generic clomid price

buy cipro cheap: CiPharmDelivery – buy cipro online usa

https://clomidonpharm.com/# order clomid

where to buy clomid without prescription: clomid on pharm – can i buy cheap clomid price

http://prednibest.com/# prednisone canada prices

buy prednisone 20mg without a prescription best price: prednisone 10mg price in india – buy prednisone 20mg without a prescription best price

amoxicillin no prescription: buy amoxicillin 250mg – where can you get amoxicillin

where to get clomid where to get clomid no prescription clomid sale

http://amoxstar.com/# buy amoxicillin 500mg usa

canine prednisone 5mg no prescription: Predni Best – prednisone 50 mg coupon

amoxicillin 750 mg price: amoxicillin discount – amoxicillin from canada

buy cipro online canada CiPharmDelivery buy generic ciprofloxacin

https://cipharmdelivery.com/# antibiotics cipro

buy cipro: ci pharm delivery – cipro pharmacy

can you get cheap clomid without insurance cost of clomid for sale can you buy cheap clomid without dr prescription

can i get cheap clomid tablets: get cheap clomid without a prescription – how can i get generic clomid without insurance

how to buy amoxycillin: Amox Star – where to buy amoxicillin 500mg without prescription

can i buy prednisone online without prescription Predni Best 50 mg prednisone tablet

http://clomidonpharm.com/# can i order cheap clomid pill

prednisone 12 mg: PredniBest – prednisone brand name in india

azithromycin amoxicillin: where can i buy amoxicillin without prec – amoxicillin 250 mg capsule

where can i get clomid pill clomid on pharm get generic clomid without prescription

https://cipharmdelivery.com/# buy cipro no rx

clomid online: clomid on pharm – can you buy cheap clomid without dr prescription

prednisone for sale no prescription prednisone tablets 2.5 mg prednisone 20 mg tablets coupon

http://clomidonpharm.com/# can i purchase clomid price

cipro 500mg best prices: п»їcipro generic – cipro online no prescription in the usa

https://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино официальный сайт

https://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино зеркало

пин ап вход Gramster gramster.ru

пин ап казино зеркало: gramster – пин ап казино официальный сайт

http://gramster.ru/# pinup 2025

http://gramster.ru/# pinup 2025

http://gramster.ru/# pinup 2025

http://gramster.ru/# пин ап вход

https://gramster.ru/# gramster.ru

https://gramster.ru/# gramster.ru

pinup 2025: gramster – пин ап

пин ап зеркало Gramster пин ап казино зеркало

https://gramster.ru/# пинап казино

пинап казино: Gramster – пин ап

http://gramster.ru/# пин ап вход

https://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино зеркало

пин ап вход gramster пин ап

https://gramster.ru/# gramster.ru

пин ап: gramster.ru – пинап казино

https://gramster.ru/# пин ап зеркало

http://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино

http://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино официальный сайт

пин ап казино зеркало: gramster.ru – пин ап вход

pinup 2025 Gramster пин ап вход

https://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино

пин ап Gramster пинап казино

пин ап: gramster – пин ап казино зеркало

http://gramster.ru/# pinup 2025

http://gramster.ru/# пин ап зеркало

https://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино

пин ап вход gramster.ru пин ап казино зеркало

https://gramster.ru/# pinup 2025

http://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино официальный сайт

https://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино официальный сайт

http://gramster.ru/# gramster.ru

http://gramster.ru/# gramster.ru

пин ап вход gramster пин ап зеркало

https://gramster.ru/# пин ап зеркало

https://gramster.ru/# pinup 2025

http://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино

http://gramster.ru/# пин ап зеркало

пин ап казино зеркало: gramster.ru – пин ап казино зеркало

http://canadianpharmacy.win/# canadadrugpharmacy com

canadian online drugstore reddit canadian pharmacy best canadian pharmacy to buy from

http://indianpharmacy.win/# best online pharmacy india

https://indianpharmacy.win/# п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

http://canadianpharmacy.win/# canadian pharmacy king

canadian pharmacy india: canadian pharmacy win – precription drugs from canada

https://mexicanpharmacy.store/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://canadianpharmacy.win/# best rated canadian pharmacy

http://mexicanpharmacy.store/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

canadian pharmacy drugs online best online canadian pharmacy online canadian pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexican drugstore online

http://mexicanpharmacy.store/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://canadianpharmacy.win/# cross border pharmacy canada

http://indianpharmacy.win/# mail order pharmacy india

http://canadianpharmacy.win/# canadian neighbor pharmacy

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: reputable mexican pharmacies online – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

best canadian online pharmacy cross border pharmacy canada canadianpharmacy com

http://canadianpharmacy.win/# pharmacies in canada that ship to the us

https://indianpharmacy.win/# best india pharmacy

http://indianpharmacy.win/# top 10 pharmacies in india

safe canadian pharmacies: best canadian online pharmacy – legitimate canadian mail order pharmacy

https://mexicanpharmacy.store/# best online pharmacies in mexico

http://indianpharmacy.win/# best india pharmacy

https://canadianpharmacy.win/# my canadian pharmacy rx

mexico drug stores pharmacies purple pharmacy mexico price list mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

https://canadianpharmacy.win/# reputable canadian online pharmacy

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexico drug stores pharmacies – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

http://indianpharmacy.win/# online pharmacy india

http://mexicanpharmacy.store/# mexican rx online

https://canadianpharmacy.win/# best canadian online pharmacy

best india pharmacy Online medicine home delivery best india pharmacy

safe canadian pharmacies: reliable canadian pharmacy reviews – canada cloud pharmacy

https://mexicanpharmacy.store/# mexican drugstore online