Gold Medal winner Billy Mills’ passion for helping Native young people starts a new program to help their dreams come true.

| 2017 Q3 | story by Billy Mills, photos courtesy Billy Mills

Billy Mills with the 2017 Dreamstarters

As a young teenager from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, I ran my first race in jeans and sneakers. The race was on the School of Mines track, in Rapid City South Dakota. I placed last in the 440-yard dash, but I found a freedom I felt I had lost forever. My father had passed away a year before, when I was 12. He had told me that he hoped I’d try sports. So, I did. I tried football; it hurt. Boxing also hurt. I was not good at basketball. I also tried rodeo, but I was even worse at that than basketball.

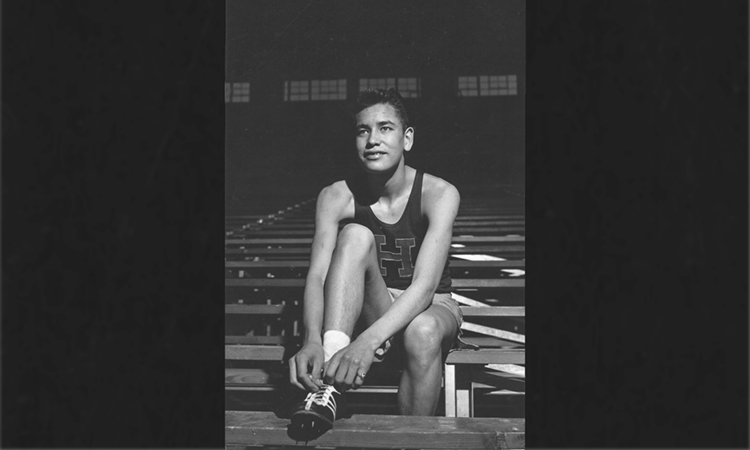

In the fall of 1953, I started high school at The Haskell Indian School, in Lawrence, Kansas. I was 5 feet 1½ inches tall and weighed 102 pounds. As a freshman, I was still no good at football and had gotten worse at basketball. Then, one day, my Haskell coach, Tony Coffin, suggested I run a distance race. I laced up my spikes and stepped out onto the track, and that was it. I knew I had found my sport. When I ran, I not only experienced the freedom I mentioned earlier, but I also felt a sacredness I could not describe. I needed that sacredness in my life. Shortly after my mother died, when I was just 8, my dad took me fishing. He said, “Son, you have broken wings.” He told me to look down deep inside myself, “way down where the dreams lie. Find your dream. The pursuit of a dream will heal a broken soul.” He told me to bring my passion together with talent, because when passion meets talent, magical things happen.

Billy Mills as a student athlete at Haskell 1957-58.

My passion for running blossomed at Haskell, where I started running track and cross-country competitively. By my sophomore year, I had won the unofficial state of Kansas Cross Country Championships. By my senior year, I had earned an athletic scholarship to The University of Kansas.

But I still had broken wings. During my junior year, I came close to suicide. But, I felt my dad’s voice, saying: “Don’t.”

I broke down in tears, took out a piece of paper and wrote: “Gold Medal, Olympic 10,000-Meter Run.” That was it. I had finally found the dream that would heal my broken soul.

And it did. Three and a half years later, in 1964, I was standing on the award podium to receive my gold medal in the 10,000-meter race at the Tokyo Olympics. I had taken the virtues and values of my culture, traditions and spirituality, and put them into my educational pursuits, my Olympic pursuits and my life dreams. They gave me the confidence, direction and clarity of mind to stay the course. Standing on that podium, I knew that the moment was a gift, and I wanted to give back.

American Indian children grow up with some of the highest rates of poverty in America. In Pine Ridge, where I grew up, and in other communities, we’re dealing with unemployment, health problems and discrimination that goes back to the days of Columbus, and carries the legacy of violence and broken treaties. So, in 1986, I cofounded Running Strong for American Indian Youth with my friend Gene Krizek. Our idea was to tackle these problems by giving money, food and basic goods to the people who needed them.

Running Strong started by providing water wells to Oglala Lakota (sometimes known as Sioux) families like mine on the Pine Ridge Reservation, and, since then, we’ve developed deep partnerships with Native communities all over the country. Our programs range from direct food and heat assistance, to projects that help Indian nations preserve traditional language and culture for future generations. Wherever we work, we bring local expertise together with the support of thousands of donors to create healthier, happier and more hopeful futures for American Indian youth.

We’ve made a tremendous difference in the lives of countless Native young people. Fifty years after winning my gold medal and more than 25 years after starting Running Strong, I wanted to find a way to address another aspect of poverty: the poverty of dreams, which robs Native youth of their ability to imagine what the future might hold.

So, on Oct. 14, 2014, the 50th anniversary of my gold medal win, we announced our new Dreamstarter program, which jump-starts dreams for Native youth. Starting in 2015, we’re choosing 10 talented young Dreamstarters each year to receive $10,000 grants for projects that help them bring their dreams to life. Each Dreamstarter partners with a nonprofit that provides mentorship and project-management support. In total, we’ll award 50 $10,000 grants over five years to celebrate the 50th anniversary of my 10,000-meter Olympic race.

KU Coach Bill Easton, Tom Dotson, Billy Mills (1958-1962)

We’ve already named the first 30 Dreamstarters, and every year, I’m astounded and humbled by their vision, creativity, talent and strength to overcome the many challenges they face. I’m inspired by Dreamstarters such as Noah Blue Elk Hotchkiss, who was just 16 years old when he was named among our first-ever class of Dreamstarters. Noah is Southern Ute, Southern Cheyenne and Caddo, and grew up in New Mexico. When he was 11, he was involved in a car accident that left him paraplegic. As a Dreamstarter, Noah partnered with the Adaptive Sports Association to bring wheelchair basketball to Native youth with disabilities who have very limited access to adaptive sports. And during his Dreamstarter year, Noah was named Junior Athlete of the Year by wheelchair basketball’s top magazine, becoming the first American Indian to win that title.

I’m inspired by JoRee LaFrance, a Dreamstarter from the Crow Tribe in Montana and student at Dartmouth College. JoRee organized traditional storytelling events with Crow elders and schools, and then worked with local youth to capture and illustrate the stories. She’s now working to publish the first-ever children’s book of Crow stories, preserving precious cultural knowledge for future generations.

And, I’m inspired by Caitlin Bordeaux, who is just starting her Dreamstarter project this year. Caitlin is a teacher at St. Francis Indian School, on the Rosebud Sioux reservation in South Dakota. When I met Caitlin at our Dreamstarter Academy training program, in Washington, D.C. this spring, she told me that only 5% of schools nationwide offer computer science courses, and in the schools that do, only 13% of the students they serve are students of color. Caitlin will start an after-school computer science program for Native elementary, middle and high school students. She hopes this will open the door for Native young people to join the tech workforce.

This year, we expanded our program with a new companion project, Dreamstarter Teacher, which gives smaller grants to teachers serving Native students. We’ve already named close to 40 Dreamstarter Teachers, with students from kindergarten through high school in schools all over the country.

It has been an incredible honor to meet and mentor these talented, passionate young people. These days, Native people and our communities are largely absent from the public conversation; media outlets almost always focus on the challenges we face, but not on the many creative and powerful ways we are working to address those challenges. Our Dreamstarters give me hope for a strong future.

I started Running Strong as my giveaway—my gift back to the communities that supported me and enabled me to achieve my dreams. But, my giveaway has become my passion, and it has healed more than just my own broken wings.

To find out more about Running Strong, Dreamstarter and Dreamstarter Teacher, please visit indianyouth.org.

Billy Mills is an Oglala Lakota (Sioux) runner and cofounder and spokesperson for Running Strong for American Indian Youth. He remains the only American to win the gold medal in the Olympic 10,000-meter event.