Two of the Oldest Businesses in Town.

| 2017 Q1 | story by Emily Mulligan, new photos by Steven Hertzog

Inside Lawrence Paper Company

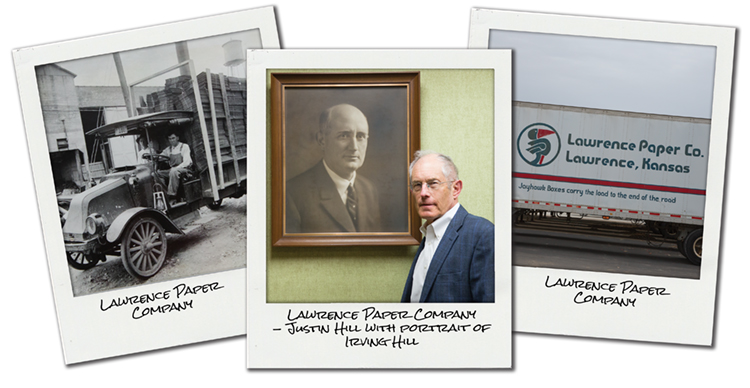

One of the oldest companies in Lawrence, incorporated in 1882, Lawrence Paper Company was the first paper mill west of the Mississippi River. Built along the Kansas River, where it was a fixture for more than 85 years, in 1971, it moved to its current location north of I-70 just west of Iowa Street. Now run by its fourth generation of owners, boxes and packing materials have always been the core of the business, and it continues to evolve with changing times and demands.

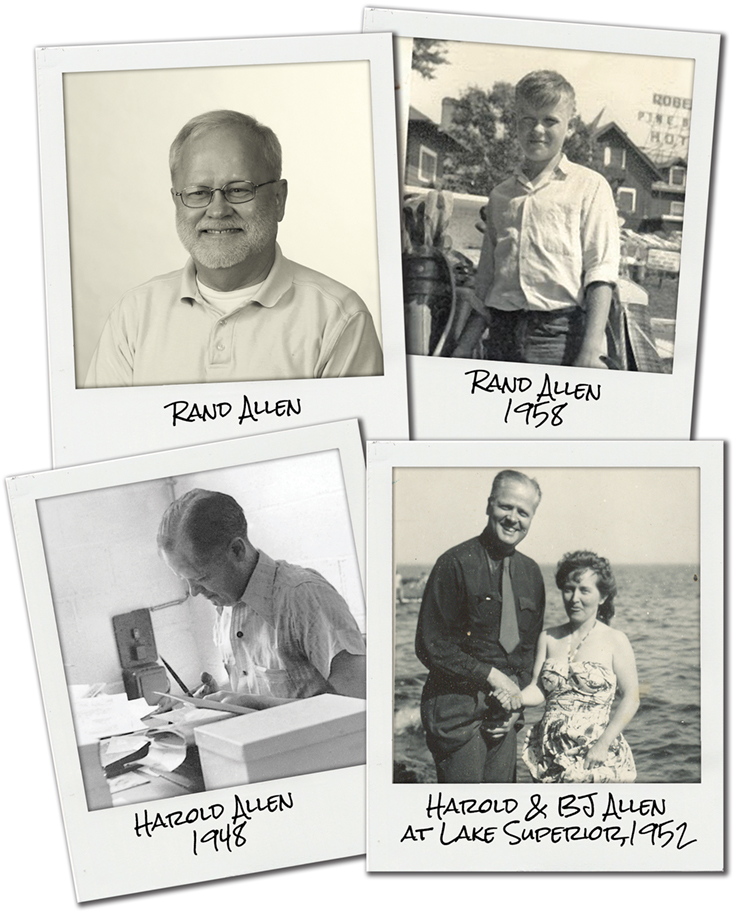

Allen Press was initially named after Harold Allen, who bought the letter shop business from Seewir Printing in 1935, where he had previously worked as an apprentice. Located below what is now Merchants Pub and Plate restaurant, at 8th and Massachusetts streets, the business moved to a much larger facility at 11th and Mass. in 1946, where it operated for 40 years until moving to a former bean-canning facility in East Lawrence, near what is now the Warehouse Arts District. Now a nationwide publisher of academic journals and books, Harold’s son, Rand Allen, is Allen Press’s president.

Lawrence Paper Company

Justin DeWitt (J.D.) Bowersock was a true entrepreneur. The mill’s first business was producing straw paper for wrapping whiskey bottles and for egg-case fillers. When Bowersock was elected to the United States Congress in 1898—for the first of what would be four terms—he turned over management of the business to his son-in-law, Irving Hill.

Hill had the mill begin producing corrugated boxes, called Jayhawk boxes, which he sold to large companies such as Ball Brothers Co., of Indiana, makers of the famous mason jars used in food canning. He also helped start a revolution in the food-canning industry by building a box sealer that made cardboard box production more efficient—and he shared the patent so that food-canning facilities could create production lines.

The company survived the Great Depression by inventing Freezurboard, which was a moisture-resistant cardboard used for shipping meat and even baby chicks. During World War II, the company sold boxes to the armed forces.

In 1957, Irving’s son, Justin Hill Sr., became the company’s president and continued to provide food industries with packaging. His third-oldest son, Alan, joined the family business in the late 1960s and began plans to relocate and expand the production facilities for the company, which, by this time, was less about paper and more about corrugated packaging. In 1971, the box manufacturing plant moved to its current location, while the mill continued to produce paper until it closed down in 1975.

Alan Hill assumed the helm in 1978 after bringing his younger brother, Justin Hill Jr., onboard a few years earlier, planning to capitalize on Justin’s financial and computer expertise.

When Alan died suddenly in 2004, Justin became president of the company, which was ever expanding its reach in the global economy. Justin has led the company in investing $20 million into manufacturing equipment, making it a state-of-the-art production facility.

Justin’s impact on the business dates back to long before he became president, however. He received his MBA from Stanford in 1972 and was poised to launch a banking career at First National Bank in Topeka, which his family owned. Various circumstances led him to come back to Lawrence Paper Company, which he says he did enthusiastically.

He advised Alan, then CEO, on financial aspects of the business while he sought to implement more computer automation, something he had studied as part of his degree.

“It was almost a put off at business school if you someday might be working for a family business,” Justin says. “Who was going to be able to afford computers? But fortunately, the cost curve came down, and I was able to do all kinds of things. My big deal was to bring everything online [on an internal computer network]so that people had computer terminals and could enter the data themselves.”

Lawrence Paper Company continues to produce cardboard boxes, but it has adapted its capabilities to the constantly changing needs of its customers. Now, the company produces custom-printed boxes that display its customers’ logo and marketing information. The company has also carved a niche in producing, designing and printing boxes that both ship and display products, such as in retail stores, where they can be opened and easily folded into a stand-up display.

“The same thing we were doing then, we are doing today, which is making a lightweight box to be delivered for distribution. The difference is that there is a higher value on promoting the brand on the box today, a lot more visual on the box to help sell the product. But other than selling on the box, what we do hasn’t changed a lot,” Justin explains.

Justin and Alan’s two oldest brothers, Steven and David, pursued their own careers as a stockbroker and lawyer, respectively, and were never involved with Lawrence Paper Company.

“Being a family business is a two-edged sword. A family-owned business typically has more continuity and culture the way they do things. But most family businesses don’t usually make it past the second generation and rarely past the third. You are only as good as your current management,” Justin says.

Economic challenges have affected the business, but thanks to conservative management and reinvestment, Justin says Lawrence Paper Company has weathered them.

“In the late 1990s and at the turn of 2000, we probably lost 40 percent of our business, because it all went overseas, and our customers closed their plants. That’s why we went from 325 employees to 200 employees. The economy wasn’t bad, but that was gut-wrenching,” he says.

Because the company was more streamlined and efficient, the housing market crash and recession in 2008 did not have as big of an impact on the company as it could have. Even with the reduction in workforce, Lawrence Paper Company still boasts many second- and third-generation employees from families.

“The people who work here, their jobs are more secure than they were 20 years ago, because they become more important the fewer people you get,” Justin says. “The best thing you can do for the employees is create a profitable, thriving business.”

As to whether the company will move on to another generation of the Hill family one day, Justin says, “I don’t have a crystal ball.”

Two of his three daughters live out of state, and his local daughter is well established in her career—although his son-in-law works for the company. He doesn’t know if his daughters will someday be involved.

“They need to do what they want to do. If they want to come work here, they’re welcome to, but that’s not been their choice,” he says.

The company is viable and prepared for the future, Justin says: “We have one of the state-of-the-art plants literally in the world. That has allowed us to be extremely competitive.”

Allen Press

Allen Press

Harold Allen bought Allen Press 82 years ago as a letter shop that specialized in printing such things as stationary and invoices. He saw the opportunity to grow the business as the economy improved after the war, expanding his operations to print things like sun visors for the University of Kansas (KU) Athletic Department, and even publishing the company’s first book, a collection of sports stories written by basketball coach Phog Allen (no relation).

Allen Press’s relationship with KU extended to the academic side, as well, when a professor at KU asked Harold to bid on printing a scientific journal called The Wilson Bulletin in 1952. That relationship began what would become a significant connection for Allen Press with the academic publication community, not just at KU but nationwide and internationally.

After half of the company’s business grew to come from academic publishing in the 1960s, Harold’s son Arly became involved in the business. Soon, the building at 11th and Mass. could no longer contain the storage and press equipment required to service its customers. Harold and Arly oversaw the conversion of a former bean-canning factory in East Lawrence into a modern printing and publishing facility. Computer programmers continued to develop networks and press technology unique to Allen Press that gave the company capabilities unlike other academic printers and publishers.

Harold passed away in 1987, and Arly became president. In 1994, Arly’s brother and Harold’s son, Rand Allen, became president.

“While not seeking a leadership position, circumstances occurred that led to changes, including my involvement. I was living overseas at the time but moved back to ensure that my father’s legacy survived and prospered,” Rand says.

Although he had been away for some time, Allen Press had been a part of Rand’s upbringing and life for as long as he could remember.

“As an 8- or 9-year-old, I had to earn spending money for the movies and the like by mopping floors and sopping up oil from presses on Saturdays,” Rand says. “I started learning skills in the bindery in my late teens.”

A great deal has changed in the world of printing since the mid-90s when Rand took the helm, so his tenure has marked change for Allen Press, as well.

In his time, the company transitioned to four-color printing capabilities, increased production volume, created an online publishing platform and other software that allow both for internal job tracking and networking among and with academic associations.

“He is a low-key guy who lives frugally. He has made so many sacrifices for the company—you just don’t see that level of dedication to a company anymore. I look at Rand like a father, he’s that special,” CEO Randy Radosevich says.

Allen Press

Radosevich has overseen a large capital outlay in the past year to replace aging and outdated equipment, as well as training the company’s 200 employees to the new technologies. Allen Press weathered the mid-2000s recession because of low debt and a dedicated customer base, particularly in the company’s academic publishing and networking groups. But Rand and his staff avoid complacency.

“Content moving from print to digital remains a continuing challenge. Newspapers are an obvious example of print having to adapt through service offerings rather than selling ink on paper. Allen Press offers a variety of other services such as editing, composition, publishing and association management that complement our manufacturing,” Rand explains.

Rand has overseen non-family CEOs during his tenure as president, but it still operates like a family company.

“Allen Press has never lost the founder’s mentality,” Radosevich says. “Being a family-owned business helps us care for our employees and customers. It also allows us to be quicker and respond to change faster.”

Will there be future generations of the Allen family at the helm of Allen Press?

“As Yogi Berra said, ‘The future is hard to predict—but it ain’t what it used to be.’ My desire would be that family would continue to respect the contributions of those that came before and maintain family ownership participation. In order to thrive, experienced and professional resources outside of family will also be necessary to keep up with the many changes in our industries,” Rand says.