Succession Plan Vital to Keeping Farm in Family

Families must have conversations, make tough decisions to keep businesses on track.

| 2017 Q1 | story by Anne Brockhoff, new photos by Steven Hertzog

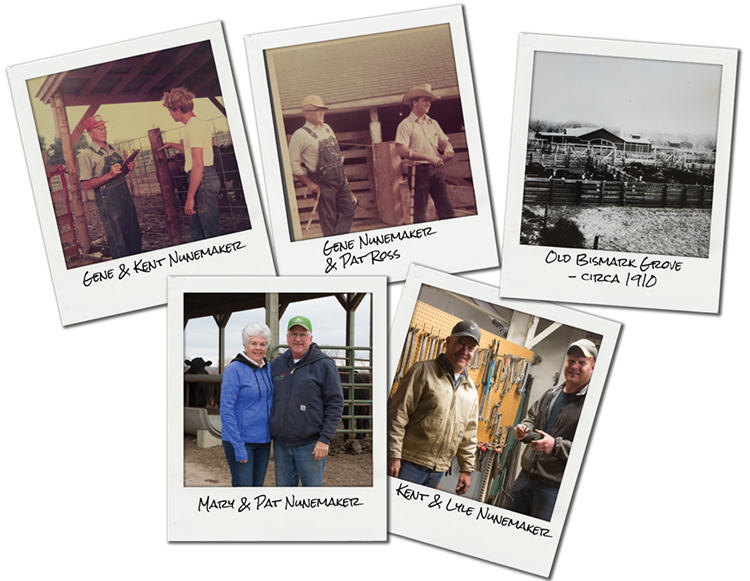

Nunemaker Ross

The story of Nunemaker-Ross Inc., like that of many area farms, hews closely to Douglas County’s history. Telling it, Mary Ross folds in bits about Bismarck Grove, the flood of ’51, the 1980s farm crisis and the current agricultural downturn.

Her tale spans five generations, from Mary’s great-grandfather to the niece and nephew whose families are now taking over. Their children will perhaps make a sixth, although Mary knows there are no guarantees.

That’s why she and the other shareholders in Nunemaker-Ross—her husband, Pat Ross, and brother and sister-in-law, Kent and Debbie Nunemaker—crafted a succession plan that ensures the farm stays in the family after they retire.

“Pat and I aren’t getting any younger. We aren’t going to be able to farm forever,” Mary acknowledges. “So we developed a plan to try to continue the farm.”

Not that it was easy. Farming and ranching are capital intensive, and each operation has its own mix of land, equipment, livestock and other assets. Debt, contractual obligations, taxes and organizational structure all come into play, as do family dynamics.

Farms and ranches often double as family homes, and it’s not unusual for farm kids to start doing chores before they start kindergarten. That gives everyone involved a deeper emotional connection than is typical in many industries. Balancing competing interests isn’t just financial, it’s personal.

There’s only one way to create a successful plan: communicate. Discussing a farm’s direction with all potential heirs might be difficult, but it’s essential, says Roberta Wyckoff, the Douglas County Extension Agent for agriculture.

“Eighty-five percent of all succession plans in ag businesses fail for reasons other than estate issues,” she says. “People have different visions of the future.”

It was through family discussions that the Rosses learned their two daughters loved the farm but didn’t want to farm. And that the Nunemakers’ kids and spouses—Lowell and Krystale Neitzel, and Lyle and Shelly Nunemaker—did.

With that in mind, Mary and other family members attended workshops and consulted their banker, attorney and friends. They folded that advice into a 10-year plan to gradually transfer Nunemaker-Ross’s assets to Bismarck Farms Inc., a corporation owned by the Neitzels and younger Nunemakers.

“It takes so much capital to farm,” Mary says. “A combine might be worth three-quarters of a million dollars, and nobody has that just laying around. You really have to figure it out.”

Their plan will hopefully allow Bismarck Farms to continue a tradition that traces back to when Mary’s great-grandfather began farming near what is now the Lawrence Municipal Airport more than a century ago. Mary’s grandparents farmed, too, and her parents, Pauline and Gene Nunemaker, followed in their footsteps.

Pauline and Gene bought Bismarck Grove, a fairgrounds famous for hosting temperance meetings in the 1870s that sat near where E. Lyon Street dead-ends at Ninth. They had established a feedyard, but that was all lost when what has been called the costliest flood in Kansas history swept through the Kaw River Valley in July 1951.

“It was devastating, both financially and emotionally, but they survived it,” Mary says.

The family rebuilt the feedlot and returned to growing row crops. Mary’s grandparents retired, and she and Pat started farming with her parents. Kent and Debbie joined them in 1980, and the couples formed Nunemaker-Ross just as rising interest rates, drought and shrinking grain exports created an agricultural recession that eventually forced thousands of family farms nationwide into foreclosure.

Nunemaker-Ross held on. They diversified their income by planting a u-pick strawberry patch in 1982 but, within a few years, switched to sweet corn. It was a hit, and hundreds of customers still flock to their garden, located on N. 1700 Road, just east of Nunemaker-Ross’s headquarters. The operation is now controlled by Bismarck Farms, which will also eventually gain control of Nunemaker-Ross’s 6,000 acres of crop ground and pasture (some of which is owned, some rented) and its 800-head cattle feedlot. The recent slump in grain and cattle prices, however, has forced transfer of those assets to slow.

“We had a plan where Bismarck Farms would be farming all the farmland after 10 years,” Mary says. “With the downturn in the economy, that’s not possible.”

Still, the plan remains in place, and Mary says all the families are determined to do what they can to see their farming heritage continue.

“We need to make sure that both Nunemaker-Ross and Bismarck Farms are able to succeed,” she says.

Succeeding at farming is getting harder, though. Prices remain low, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service forecasts a 5.2 percent rise in farm debt in 2017. Farm sector equity (the net measure of assets and debt) and financial liquidity measures such as working capital are also weakening, the agency says.

Land values add to the challenges. Nonirrigated farm ground sells for an average of $6,640 an acre and pasture for $4,000 an acre in Douglas County, Wyckoff says. That’s significantly higher than in neighboring Jefferson and Franklin counties because of greater demand from both farmers and urban development.

“There’s huge competition for land in our county,” she says. “There’s really no issue with people wanting to come back and get that ground, it’s just a matter of somebody being able to afford it.”

All that makes succession planning critical, but it’s the most important conversation families aren’t having, Dr. Gregg Hadley, assistant director with Kansas State (KSU) Research and Extension said in January during the first in a series of succession planning workshops co-hosted by KSU and Kansas Agricultural Mediation Services.

“(Succession planning) is about transferring assets to the next generation, but it’s also about transferring management,” Hadley says. “I like to call this training the next farm CEO.”

But that’s easier said than done after a lifetime as the sole decision maker, says Larry Schaake, of Schaake Farms Inc.

“I’ve always done it myself and didn’t have to think about it,” Larry says. “That’s the hardest part.”

Larry’s grandfather began farming along the Kansas River east of Lawrence in the 1880s, and his parents followed the same path. When Larry was about 10, his folks moved to a farm on E. 1500 Road; when he was 17, his father died, and he took over.

Larry and his wife, Janet, raised four children on the farm and expanded it from what he calls “not a lot of ground” to 1,000 owned and rented acres of corn and soybeans, 300 acres of pasture and 60 Simmental-Angus cows. Most Lawrence residents don’t know anything about that, though. What they do know is that the Schaake family also grows 30 acres of pumpkins.

What began as a 4-H horticulture project in 1975 is today a u-pick operation complete with a hay ride, games and activities. Many longtime visitors even bring their own children and grandchildren out to what’s become one of the region’s biggest autumnal attractions.

“It’s nothing to have 2,000 or 3,000 people here on a weekend,” Janet says.

Although the pumpkin patch is open only in October, it is a year-round enterprise. Janet orders seed for the 100 different varieties of pumpkins they plant, as well as ornamental gourds and Indian corn, in January. Planting begins in mid-June, followed by managing all the things that can go wrong, from too much or too little rain, to diseases like powdery mildew and pests.

And then there are the weeds. Once the plants are established, Larry and Janet, their children and all 10 grandchildren begin hoeing them. Three of the families are nearby— Sheila and Dan Lynch, Shari Schaake and Sharla and Rusty Dressler all live within a mile or two of the farm. Scott and Kandi Schaake drive over from Westmoreland, Kansas.

Theirs is more than sweat equity. The family formed Schaake’s Pumpkin Patch LC about five years ago, giving Larry and Janet each a 10 percent stake in the corporation and 20 percent to each of their kids. As for the rest of the farm? They’re still figuring that out, Larry says.

They’ve been working with their accountant, and they’ve drawn up a will. Rusty helps on the farm in the spring and fall, and one of their grandsons is also interested in getting into the business after he graduates from KSU this year. But actually planning for who will take over, when and how is a discussion they still need to have with their children.

“The kids have a hard time sitting down and talking to us about it, because they don’t want to think about it,” Janet says.

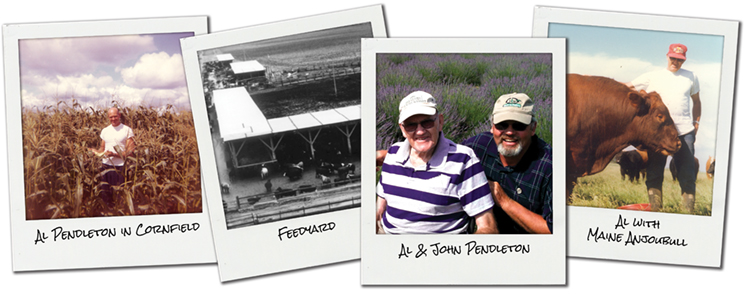

Succession planning typically assumes that a farm will stay in the family. What happens when the family doesn’t want it? You make different plans, say John and Karen Pendleton, the sole proprietors of Pendleton’s Country Market, on the southeast side of Lawrence.

“We’re not going out of business or quitting, but (the farm) is always for sale,” Karen explains.

John grew up on the farm, and, after graduating from college and marrying Karen, the couple returned to it. They helped his folks manage a cattle feedlot and 1,000 acres of row crops until the farm crisis, which hit the Pendletons as hard as it did their neighbors.

They persevered and diversified, adding a half-acre of asparagus and then hydroponic tomatoes. By the 1990s, they’d cut down on rented crop ground and closed the feedlot to grow more vegetables, bedding plants, flowers and perennials for their on-farm store and the Lawrence Farmers’ Market. Then, in March 2006, a powerful microburst leveled two silos and damaged or destroyed almost every building, vehicle and piece of equipment they owned. They considered quitting all together, but when some 300 people arrived to help clean up, they knew they couldn’t.

“The community would not let us quit,” John says. “That is something we take seriously and that we really appreciate.”

They rented out the remainder of their crop ground and focused on garden and market ventures. Their farm now includes 20 acres of u-pick asparagus and another 20 of vegetables and flowers for their own store, their farmers’ market stall, 160 CSA (community-supported agriculture) customers, a handful of restaurants and Karen’s wedding florals business. When their customers hear that none of the Pendletons’ three children plan to take over, “people are surprised we aren’t distraught,” John says.

“The fact that our kids aren’t coming back isn’t a problem,” he says.

Instead, the Pendletons are looking for the right buyer, and there’s tremendous freedom in that, John says.

“I am so glad we are not a Century Farm,” he says, referring to a Kansas Farm Bureau program that recognizes farms whose current owner or operator is related to the owner of 100 years earlier. “If my grandfather and great-grandfather were farmers, the pressure for me continuing the farm would be incredible.”

That’s a freedom shared by Roger and Teresa Flory, of Flory Family Farms. Roger spent time on his grandfather’s farm while growing up; when he married Teresa, they knew that’s how they wanted to raise their own family. They began farming on a small scale and then got into hogs in 1988, when one of their three sons decided to show them in 4-H. The boys are all grown, married and have off-farm jobs, but everyone, including the five grandchildren, remains involved.

“What’s really nice about it is that all three of my sons are up here virtually every night,” Roger says. “What one can’t do, the other one picks up the difference. It’s a full-time deal, but we divide it four ways.”

Tim and Jana Flory raise Boer goats for meat, breeding and 4-H projects. Brian and Julie Flory, and Mark and Jessica Flory are partners in the family’s farrow-to-finish hog operation. They and Roger each own their own hogs, between them raising purebred Yorkshire, Spots, Hampshire and Duroc hogs, plus crossbreds. Their 20 sows farrow twice a year, producing between 150 to 200 pigs they sell as breeding stock, as projects for 4-Hers or to supply meat to customers at the Lawrence, Clinton Parkway and Merriam farmers’ markets. Revenue from the market pigs goes back into the farm to pay shared expenses.

“If there was anything left over, we’d divide it,” Roger jokes when asked about how they split any profits.

Dividing assets equally is also their plan for the future, although that sounds more complicated than it is, Teresa says. The couple owns the farm’s 75 acres, its facilities and a handful of equipment, and both work full-time in Lawrence. Each of their sons owns his own livestock, vehicles and other assets.

“Our situation is different” from a family whose entire income is derived from the farm, Teresa says. “We own our own places, our own land. Those things aren’t tied up.”

The goal was never to build and protect a farming legacy. Rather, it was to share a love of farm life with their families.

“This is all about our family and the kids, and our grandkids being able to experience this lifestyle,” Roger says. “They may not choose to do it or be able to do it, but at least they got to experience it.”

Schaake