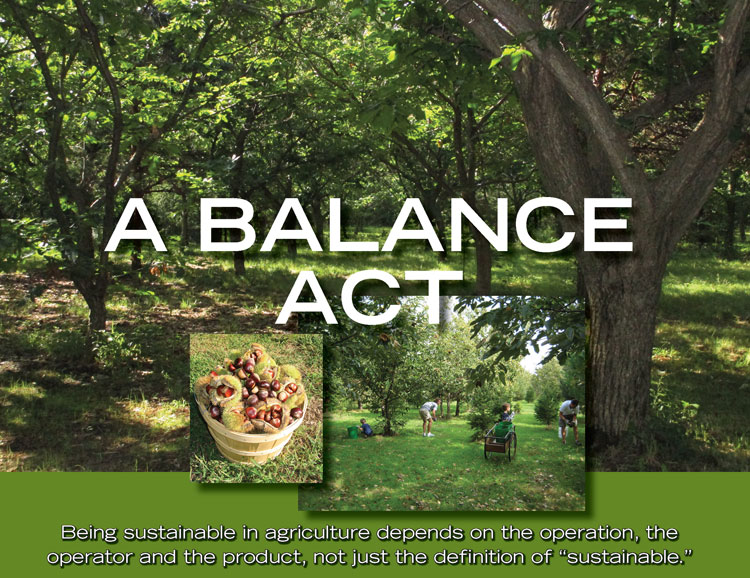

Being sustainable in agriculture depends on the operation, the operator and the product, not just the definition of “sustainable.”

| 2020 Q1 | story by Anne Brockhoff | photos by Steven Hertzog

Chestnut Charlie’s farms, photos courtesy Chestnut Charlie’s

Sustainability is one of agriculture’s hottest buzzwords, and for good reason. Producing food impacts the environment, the economy and the community. Yet, there’s no one-size-fits-all definition of the word.

Practices that work in the Kaw River Valley might not in western Douglas County, where soil is thinner and rockier. Farmers’ market finances differ from those of the global commodities market. Big, small, conventional, organic, market garden, cattle, crops—they’re all different but can be sustainable in their own ways.

“It’s kind of tricky to define, but what’s true in general is that many farmers really focus on what’s sometimes called the ‘triple bottom line,’ ” says Tom Buller, the horticulture Extension agent for K-State Research & Extension—Douglas County.

The phrase encompasses environmental, economic and social sustainability. All three are essential, but there are as many ways to balance them as there are farmers.

For Charlie NovoGradac and Deborah Milks, chestnuts are the key. Chestnut Charlie’s Tree Crops has been certified organic since 1998, and its 1,500 chestnut trees are surrounded by a shelterbelt that buffers them from chemical drift and provides food and shelter for wildlife. Planting cover grasses and other organic practices improve soil fertility and otherwise benefit the environment, NovoGradac explains.

“Sustainable to us, as farmers, means production can be maintained indefinitely at a certain level” without depleting resources or using potentially harmful or synthetic chemicals, he says.

Not that it’s easy. Chestnut trees don’t begin producing until they’re about 12 years old and take 20 years to reach full production. That adds up to years of weeding, pruning, mowing, planting cover crops, irrigating and other maintenance before seeing any return from or claiming depreciation on the investment.

NovoGradac could boost his harvest by using conventional methods, but organic farming is what he calls a “bargain of principal.” It requires additional office work, record keeping and inspections, and insects and weeds must be controlled by hand. Chestnuts can’t be mechanically harvested, so NovoGradac hires about 50 part-time workers to collect nuts daily as they fall.

Still, it’s worth it, NovoGradac says. Organically managed trees benefit the environment, and “our profits from less than 20 acres exceed profits from hundreds of acres of corn or soybean farming,” he says.

Scott Thellman, owner of Juniper Farms, tends to his heirloom tomatoes

and his mixed greens.

Balancing Environment and Economics

Scott Thellman, of Juniper Hill Farms, settled the sustainability question in this way: He raises both conventional and organic crops.

“I’m fortunate to be a first-generation farmer that can see it both ways,” says Thellman, who this year was a national contestant for the American Farm Bureau Federation’s Young Farmers & Ranchers Achievement Award.

Thellman began custom-haying during high school and was farming seriously by the time he started college in 2010. After graduation, he expanded his hay and row-crop operations, then added his first hoop house after winning a grant for young farmers. He soon began converting acreage to organic and experimenting with vegetables.

He now farms about 150 USDA-certified organic acres and 400 more using environmentally friendly practices. Technologies such as variable-rate fertilizer (VRF) application allow him to apply precise amounts of fertilizer to each part of a field, thereby reducing input use and increasing yields. But, he avoids other common conventional practices, such as applying anhydrous ammonia fertilizer, when they don’t fit his philosophy.

“Will this land be fertile and viable for the next generation and beyond? I really think about that,” Thellman says.

He also raises about 50 acres of vegetables that he sells throughout Lawrence and greater Kansas City. Thellman invested in on-farm cold storage and a refrigerated delivery truck to manage the volume, but that created new challenges.

“We can’t grow year-round, but we had infrastructure we had to pay for year-round,” Thellman explains.

His solution: to create a distribution and brokerage business through partnerships with other growers that lets him better serve customers, reduce his carbon footprint and up the bottom line.

Not that Thellman—or many—farmers are feeling flush these days. Although the U.S. Department of Agriculture in February predicted net farm income will this year rise 3 percent to $96.7 billion, other statistics paint a different picture.

Net cash farm income (a measure of cash flow) is seen falling 9 percent to $109.6 billion, while total production expenses and farm debt are increasing. Farm bankruptcies also jumped 24 percent in the year ending September 2019, according to the American Farm Bureau Federation.

All this has Karen Pendleton, of Pendleton’s Country Market, comparing last year’s floods, U.S.-China trade war and slow economic growth with conditions in the 1980s, when an intense heat wave, Russian grain embargo and soft economy culminated in what’s known as the Farm Crisis.

“We have almost the same thing coming around right now, so it’s a little creepy thinking what could be happening to a lot of farmers,” Pendleton says.

Karen Willey fixes fences; L top: Karen Willey with friends; L bottom: Karen and her daughter feed their cattle

Flexibility Equals Survival

Such uncertainty requires flexibility, which Pendleton and her husband, John, know all about. When they began farming in the ’80s, John’s family owned a cattle feedlot and had 1,000 acres of row crops. As the Farm Crisis unfolded, they began transitioning to value-added crops including asparagus, hydroponic tomatoes, bedding plants, flowers and vegetables, and selling them through an on-farm store, a CSA (community-supported agriculture) and farmers’ markets.

Then, in March 2006, a powerful microburst damaged or destroyed almost every building, vehicle and piece of equipment they owned. They rebuilt, only to have a tornado do much the same thing again in May 2019.

Before the tornado, sustainability meant using biological controls in the greenhouses and mowing weeds and grass instead of spraying. In 2020?

“Sustainability right now is cleaning the farm up so that it can stay open,” Pendleton says.

Ag’s Impact

Even as they were still removing damaged structures, the Pendletons continued selling what they could at the Lawrence Farmers’ Market. The market is perhaps the best window some Lawrence residents have into agriculture, but it does more than connect consumers with farmers, market manager Brian McInerney says.

Market shoppers come from Topeka, Kansas City and elsewhere, and many also visit other stores and restaurants. Its 70 vendors—all of whom are located within a 50-mile radius—buy food, fuel and other supplies, as well as pay taxes and wages. But, agriculture’s impact goes well beyond the market. USDA data from 2017 shows the Douglas County’s 998 farms together generated $65.87 million in crop and livestock sales, and employed 817 people.

Among them is Karen Willey, a one-time city girl whose family now has chickens, goats, a garden and orchard on 80 acres south of Lawrence. Willey’s favorite enterprise, though? Her small herd of British White Park cattle, which she learned to manage largely by tagging along with her neighbor, Lee Broyles.

“(Willey) showed up way back and started riding with us in calving season, and got to where she could pull a calf,” says Broyles, who raises Red Angus cattle and row crops and sells his grass-fed Broyles’ Beef at Checkers Foods and direct to consumers.

Farming isn’t for the faint of heart thanks to extreme weather events, tumultuous commodities markets and rising property taxes. To make it work, Broyles partnered with neighbors Wes Flory and Terry Henry to share labor and equipment. Willey joined in, helping work cattle, feed hay, plant fields and anything else that needs to be done.

She brings insight into regenerative agricultural practices (a term she prefers to “sustainable”), while Broyles readily shares his experience and his pragmatism.

“I pay my bills with what I make off the farm,” he says. “Sustainable is what you’re doing in agriculture that makes a living. It ain’t an easy deal.”

One thing they agree on: No-till farming and planting cover crops are necessary for optimum soil health.

No-till is what it sounds like: planting crops without tilling the soil. The practice retains moisture, reduces compaction, builds organic matter and benefits soil organisms. Broyles and Willey also plant cover crops including rye, millet, sorghum and legumes to add nutrients and improve soil structure.

Grazing is the third component. Both Broyles and Willey use rotational-grazing methods, moving cattle regularly to fresh pasture or fields planted to cover crops to make best use of the forage and allow each patch to recover.

“That’s the piece of the story that gets lost,” Willey says. “That land stewardship with grasslands can only occur with grazing animals. Done right, cattle can heal the land.”

Karen and John Pendleton tend to their tomatoes in their greenhouse then sit and relax on their new porch outside their Country Market.

Telling the Sustainable Story

It’s not the only lost story, says Brenna Wulfkuhle, of Rocking H Ranch. Consumers are often unfamiliar with various practices or don’t appreciate how devoted farmers are to the well-being of their land and livestock.

“We’ve got to tell our story,” says Wulfkuhle, who regularly posts about farming on the ranch’s Facebook page. “No one’s going to tell it for us.”

Wulfkuhl’s husband, Mark, is a third-generation rancher, and the couple runs about 500 cows; raises corn, soybeans, wheat and hay; has a small family feedlot; and operates a custom chemical and fertilizer application company.

Their idea of sustainability is leaving the land in the same or better shape than when they began. To do that, the Wulfkuhles use pasture rotation, soil-testing and other techniques, and they’ve practiced no-till and planted cover crops for more than 25 years.

“We put a pencil to it and saw it helped us cut back on costs, so we continued to do it,” Wulfkuhle says.

The economics have to work, because the ranch supports their family as well as their one full-time and two or three part-time seasonal employees. Another priority: giving everyone a break on weekends. That can be difficult when farming feels like a 24/7 job, but it’s important.

A farm that “produces a decent economic return and is maybe ecologically sustainable can be almost crushing for the farmers in the amount of work they face, and the stress,” K-State’s Buller says.

Seeking Social Sustainability

Managing stress is crucial considering that men who farm or ranch are more likely to commit suicide than men in other industries, according to a recent Centers for Disease Control report. The issue is so concerning that the Kansas Department of Agriculture and its partners in December launched KansasAgStress.org to provide resources and support for those suffering ag-related stress and mental health issues.

Juniper Hill’s Thellman acknowledges the pressures associated with agriculture can be significant.

“I am a workaholic, especially in summer,” he admits. “But, I do have respect for my crew.”

Thellman pays employees a living wage and overtime, and tries to support them in other ways. Like most farmers, he’s quick to help neighbors and assisted with the Pendletons’ cleanup effort. The Pendletons, in turn, urged people to reach out to less-well-known farms that also suffered damage.

All the farmers interviewed in this story serve on committees and boards of directors for organizations ranging from the Douglas County Extension Board, Growing Lawrence, Douglas County Farm Bureau and Douglas County Food Policy Council to the Lawrence-Douglas County Planning Commission and countless other community groups.

That sort of social sustainability centers on caring for people, but it’s only successful when combined with the environmental and economic components. Then, the result is positive for the whole of Douglas County.

“Whether you’re a large-scale producer, organic or conventional, selling at the farmers’ market or shipping internationally, we’re all in it together,” Thellman says. “That’s the ag mentality, and hopefully it will drive this next generation.”

Links:

- Chestnut Charlie’s: https://www.chestnutcharlie.com

- Scott Thellman, Juniper Hill Farms: http://www.jhf-ks.com

- USDA farm income forecast: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-sector-income-finances/highlights-from-the-farm-income-forecast/

- Farm bankruptcies: https://www.fb.org/market-intel/farm-bankruptcies-rise-again

- Pendleton’s: http://pendletons.com

- Lawrence Farmers’ Market: http://www.lawrencefarmersmarket.org

- Kansas ag stats:

- Broyles’ Beef: http://www.broylesbeef.com

- Rocking H Ranch: https://www.facebook.com/rockinghranchinc/

- Farm suicides: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p1115-Suicide-american-workers.html